Assessing SimNIBS: A Comprehensive Review of its Application in Clinical Studies for Neurological Disorders

- Biomedical Engineering Department, Annexee Building, L D College of Engineering, Opp Gujarat University, Navrangpura, Ahmedabad- 380015, Gujarat Technological University, India

- Department of Biomedical Engineering, Government Engineering College, Sector-28, Gandhinagar-382028, Gujarat Technological University, India

Abstract

Background: Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is used to modulate brain function in both healthy and diseased states. Applying a direct current to the scalp via stimulating electrodes results in local excitation or suppression of neural populations. The effects of stimulation can be characterized by the electric field (E-field) generated in targeted brain regions. Therapists are unable to measure these potentials in vivo. To visualize the electric fields, many open-source software packages have been employed to improve understanding of the flow and distribution of current injected through the stimulating electrodes.

Methods: We reviewed original clinical studies that applied tDCS to various neurological disorders and normal cognitive functions. We examined electrode locations, dosage parameters, pathological conditions, stimulation protocols, and clinical outcomes. Electric field strength and focality were assessed with computational modelling using the Simulation of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation (SimNIBS) platform. Our goal was to identify differences between the in-vivo E-fields and those predicted by the model. SimNIBS was chosen as the exclusive modelling tool for this study.

Results: A total of 100 research articles combining clinical data and E-field modelling were included, encompassing more than 3,856 patients and healthy subjects. SimNIBS has been applied to estimate E-fields across diverse neurological and psychiatric applications. By simulating current intensity, focality, and spatial distribution, researchers can relate these parameters to therapeutic outcomes and advance the understanding of neuromodulatory mechanisms.

Conclusion: SimNIBS, with its versatile capabilities and robust computational framework, is attracting growing interest among neuroscientists and biomedical engineers by providing precise predictions of E-field distribution. By simulating parameters such as current intensity, focality, and distribution, researchers are able to correlate stimulation settings with therapeutic outcomes and deepen the future understanding of neuromodulatory effects.

Introduction

The application of therapeutic electrical currents for neuromodulation has attracted growing interest among neurotherapists. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive technique used to facilitate or inhibit neural activity in both pathological and healthy conditions. When determining the stimulation dose, clinicians must consider the targeted cortical location, inter-individual variability (e.g., tissue conductivity, head geometry, medical history) and the desired therapeutic outcomes. Two key biophysical parameters in tDCS are the induced electric field strength and the resulting current distribution. Electric field strength (E) denotes the intensity of the field generated by the tDCS electrode montage and is typically measured in volts per meter (V/m). Within tDCS, E is governed by the potential difference between the anode (positive) and cathode (negative) electrodes, and the field extends from the anode to the cathode. The magnitude of the electric field strength is influenced by various factors, including electrode size, placement, current intensity, and tissue conductivity. Current distribution describes the pathway of charge flow through cerebral and extracerebral tissues during stimulation; current travels from the anode to the cathode, creating a direct-current circuit that depolarizes or hyperpolarizes neurons in the underlying brain regions. The distribution is non-uniform and depends on head-tissue geometry and conductivity, as well as electrode size, shape, and placement. In vivo tDCS studies often employ computational modeling to predict intracranial electric field strength and current distribution. These models incorporate the individual’s head anatomy, electrode placement, and the electrical properties of scalp, skull, cerebrospinal fluid, and brain tissue to estimate the field distribution. Researchers use these models to optimize tDCS protocols and ensure that the targeted regions receive the desired stimulation while minimizing off-target effects. A sound understanding of electric field strength and current distribution is critical for both safety and efficacy in tDCS applications, as different levels and patterns of stimulation can produce distinct neuromodulatory effects 1.

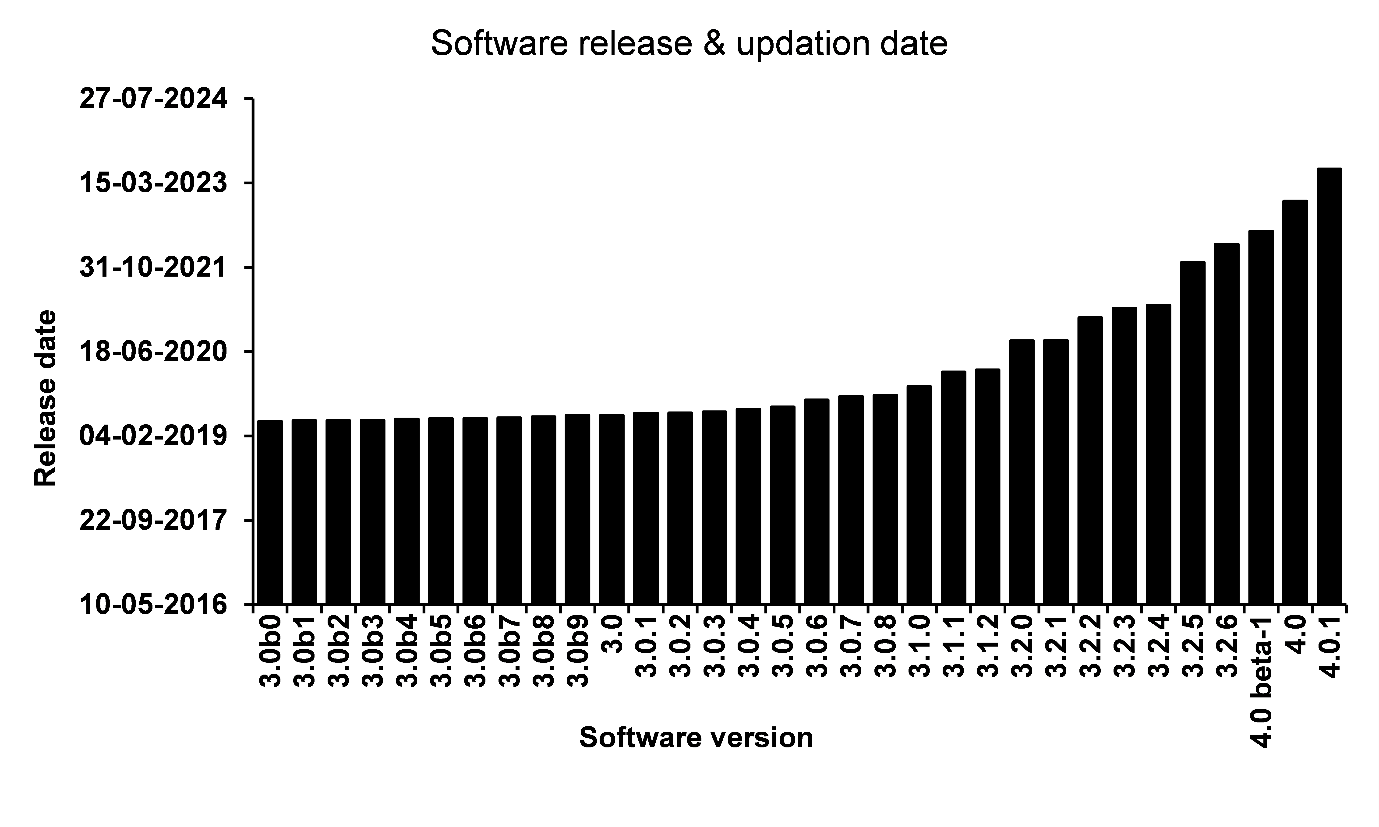

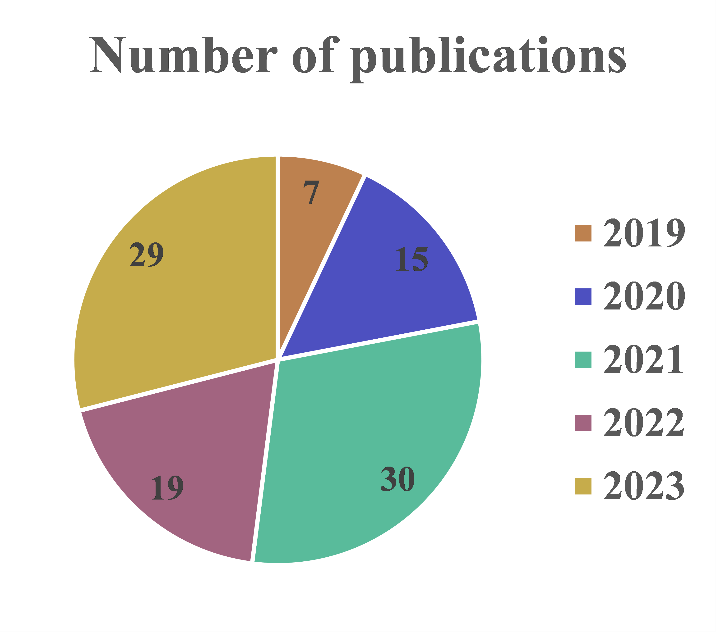

Several proprietary and open-source software packages are available to characterize and analyze electric field strength and current distribution, including COMSOL Multiphysics, the Realistic Volumetric Approach to Simulate Transcranial Electric Stimulation (ROAST) 2, Simulation of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation (SimNIBS) 3, SPHEARES 4, and SCIRun 5. Among these platforms, ROAST and SimNIBS are the most widely cited—**225 and 800 citations, respectively, up to April 2022—**for modeling electric fields and current distributions 6. Mohigul Nasimova et al. evaluated ROAST for clinical validation and reported that it is more robust than SimNIBS 6. Both SimNIBS and ROAST use MRI-derived three-dimensional head models to simulate tDCS in individual subjects 7. SimNIBS additionally supports simulations of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS), in which sinusoidal currents modulate cortical neurons. Between 2019 and 2023, two major versions of SimNIBS (3.0 and 4.0) and 32 incremental updates were released, adding new utilities, enhanced operating-system compatibility, and security patches (Figure 1).

SimNIBS versions with timeline.

With respect to features and workflow, SimNIBS can be compared with other freeware packages such as ROAST, COMET, BONSAI, and SPHEARES. SimNIBS, ROAST, and COMET provide automatic segmentation of T1- and T2-weighted MRI, standard conductivity assignment, electrode placement, three-dimensional mesh generation, and finite-element solvers. BONSAI supports only electrode placement for visualization and cannot perform MRI-based E-field analysis. SPHEARES lacks automatic T1/T2 segmentation, resulting in non-patient-specific E-field visualizations.

Minimum system requirement for simulation software

| Simulation platform | System Requirements | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating System | Hardware Dependencies | Software Dependencies | |

| SimNIBS | Windows-based: Windows-7 & 10, Linux based: Ubuntu 16.04, 18.04 and CentOS 7, macOS: 10.13 (High Sierra) | Minimum 6GB RAM and 8GB for optimum performance, holds 3 GB space | MATLAB, FSL, Freesurfer |

| ROAST | Windows-based: Windows-7 & 10 | Intel i3 or higher, 4 GB RAM or higher, ≥ 50 GB to run NEWYORK HEAD | MATLAB |

| COMET | Windows-7 & 10 | Intel i5 or higher, 8 GB RAM (dependent on mesh size) or higher | MATLAB |

| BONSAI | Web-based application (Runs on typical system configuration) | ||

| SPHEARES | Web-based application (Runs on typical system configuration) | ||

In this review, we focused on studies that employed SimNIBS across diverse clinical investigations. These investigations analyzed multiple parameters to model and compare therapeutic outcomes of tDCS in neurological disorders. We report stimulation dose, target site, neurological indication, and other relevant factors incorporated into in vivo modeling.

Methods

Literature Search

To structure our review of clinical research on neuromodulation with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and the use of SimNIBS for computational modeling, we applied the search string “tDCS clinical trials AND neurological conditions AND SimNIBS.” We limited the retrieval to studies published between 2019 and 2023. Records describing deep-brain stimulation, narrative reviews, editorials, pre-prints, and letters to the editor were excluded.

Citation Report

Between January 2019 and October 2023, SimNIBS was cited 711 times in peer-reviewed publications, including original investigations and reviews. The same search string (“tDCS clinical trials AND neurological conditions AND SimNIBS”) was used to map these citations across clinical studies and review articles.

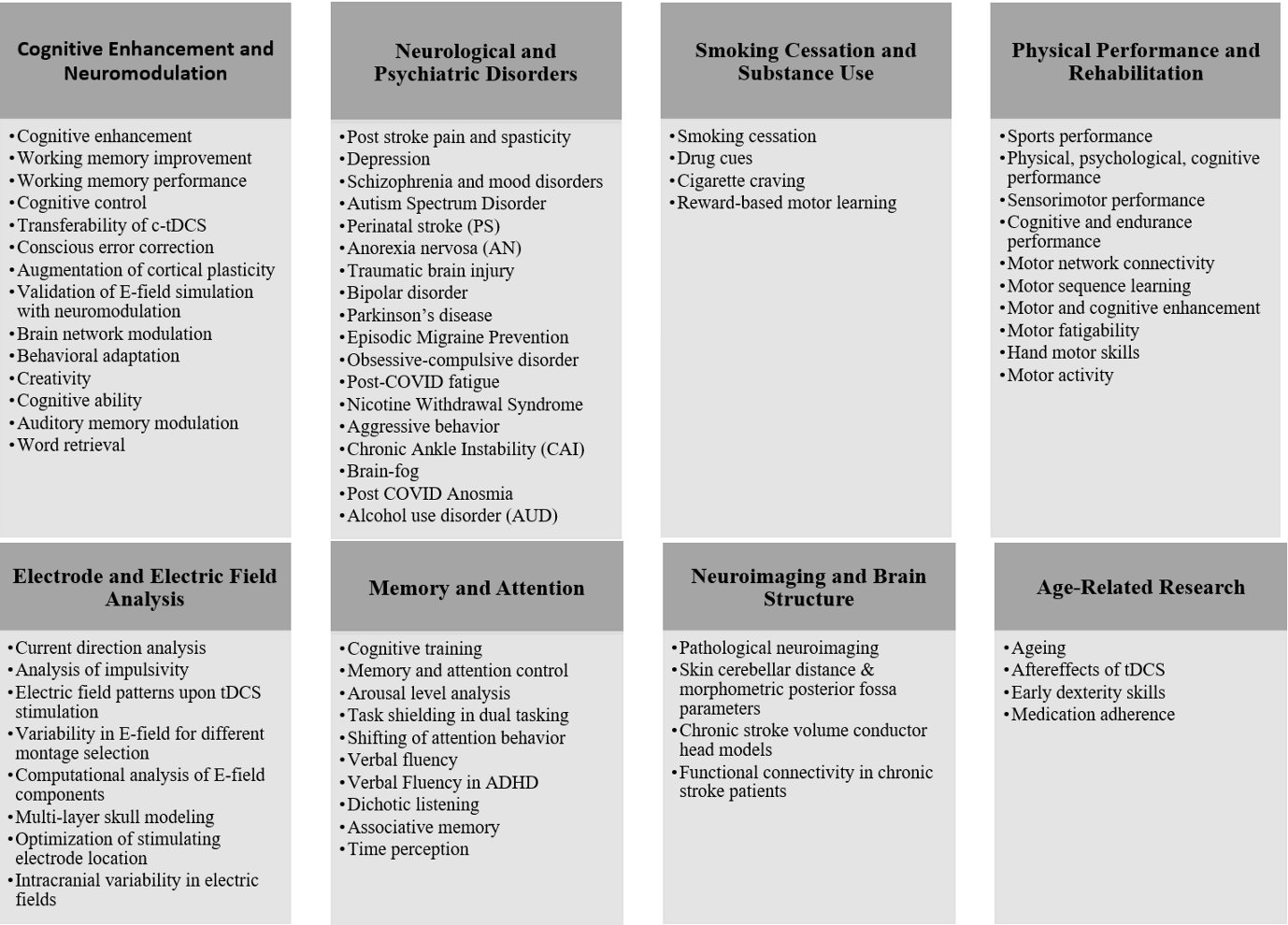

Applications of tDCS and Its Modelling with SimNIBS in Clinical Research

The Objective of this analysis was to delineate the clinical applications of tDCS and their simulation in SimNIBS across neurological and psychiatric disorders. Stimulation paradigms reported in the literature and their corresponding computational models were systematically extracted. Modelling of tDCS outcomes can be categorised into 1 fully quantifiable metrics, such as electric-field magnitude and focality, and 2 partially quantifiable endpoints, including cognitive enhancement, memory restoration, and neuroplasticity, inferred from behavioural and motor assessments. The present review summarises therapeutic protocols implemented by clinicians, specifying current delivery sites, targeting approaches, current intensity, stimulation duration, and electrode montage. Additional variables considered include participant selection criteria, study hypotheses, and inter-individual anatomical variability.

Results

We selected 100 research articles from Google Scholar, filtering results published between 2019 and 2025 by year and keyword relevance, because including all 711 initially retrieved papers would have rendered the review excessively long.

Clinical and non-clinical studies that used SimNIBS to model/analyze/predict therapeutic outcomes

| Sr. No | Reference | Application | Patient characteristics | Total number of subjects/patients/simulations | Targeted Area of Brain | Selection of electrode (Anode & cathode) | SimNIBS version used | E-field and other parameters measured | Therapeutic outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andrés Molero-Chamizo et al. | Post stroke pain and spasticity | Three stroke patients | (2-Females, (Age- 43 & 72) , 1-Male, (Age- 57)) | Motor cortex | Anode- Right motor cortex, Cathode- Left motor cortex, C3/C4 according to the 10-20 EEg electrode placement method | V 3.1.2 | Electric field intensity- 0.36 V/m | Spasticity improved with varying inter-individual variability. |

| 2 | Paulo J. C. Suen et al. | Depression | Major depressive disorder during an acute depressive episode per DSM-5 criteria (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition) | 16 (n) Patients (Aged between 18-75 years) | DLPFC & ACC | Anode- F5, Cathode-F6. | V 3.1 | Electric field intensity- 0-0.63 V/m | Association observed between simulated E-field and DLPFC/ACC and depression scores. |

| 3 | Shinya Uenishi et al. | Schizophrenia and mood disorders | Major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, healthy controls. | Major depressive disorder (n = 23), bipolar disorder (n = 24), schizophrenia (n = 23), and healthy controls (n = 23). | Frontal lobe | Anode- F3, Cathode-F4. | V 2.1.1 | Not mentioned | The groups diagnosed with schizophrenia and major depressive disorder exhibited notably reduced e-field strength at the 99.5th percentile when compared to the E- field strength observed in the healthy control group. |

| 4 | Karin Prillinger et al. | Autism Spectrum Disorder | Fulfilling International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 criteria for ASD and diagnosed with ASD from a trained professional using the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised | 20 (n) male participants (aged 12–17 years) | DLPFC | Anode at F3 and Cathode Fp2-supraorbital) | V 3.1 | 0- 1.0 mV/mm | On-going study. |

| 5 | Helen L. Carlson et al. | Perinatal stroke (PS) | Arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) or periventricular infarction (PVI)] and typically developing controls (TDC) | AIS (n= 21), PVI (n= 30), TDC (n=32). | Motor cortex | Montage-1 (Anode (A)- C3/C4, Cathode (C)- Fp1/Fp2) Montage-2 (A- Fp1/Fp2, C- C3/C4) Montage-3 (A- C3/C4, C-C3/C4) Montage-4 (4×1, A-C3, C- CP5, FC5, FC1, and CP1) Montage-5 (4×1, C-C3, A- CP5, FC5, FC1, and CP1) | V 3.2.3 | For Montages- (1-3) - 0- 0.4 V/m. For Montages- (4-5) - 0- 0.25 V/m. | Children with Acquired Ischemic Stroke (AIS), tDCS configurations employing active anodes positioned over the damaged cortex exhibit variations in electric field (EF) intensity when contrasted with a control group. |

| 6 | Andreia S. Videira et al. | Cognitively Normal | SimNIBS head model | Standard brain (n=1) | Whole brain regions | Anode- C3, Cathode- C1, Cz, C2, C5, Cp1, FC5, T7, FC3, TP7, F3, AF3, TP9, Pz, Cp3, P2, P3, PO3. | V 3.2 | One anode, Five cathode configuration. 0.265- 0.585 V/m. | Crucial factor in determining the distribution of the electric field is the spacing between electrodes, rather than the quantity of electrodes used. It shows that achieving precise stimulation with fewer electrodes can be effective. |

| 7 | Yuki Mizutani-Tiebel et al. | Depression, Schizophrenia. | Subjects had a primary diagnosis of MDD according to the DSM-5 criteria. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-21) score was equal to or greater than 15. SCZ were diagnosed with ICD-10 F20 | MDD (n = 25), SCZ (n = 24), HC (n = 25). Total- 74. | Frontal lobe | Anode-F3, Cathode-F4 | V 2.0.1 | Average 0- 0.3 V/m, Standard Deviation (SD)- 0- 0.2 V/m. | There were notable distinctions in electric field strengths between clinical and non-clinical groups, along with a general variation among individuals. |

| 8 | Laurie Zawertailo et al. | Smoking cessation | Healthy smokers, standard varenicline treatment concurrently for the 12-week. | 50 healthy non-smokers | Frontal lobe (DLPFC) | Anode-F3, Cathode-F4 | Not mentioned. | 0-0.224 V/m | Merging both interventions (i.e. Varenicline & tDCS) has the potential to enhance quitting success rates compared to using either treatment alone, offering smokers a more potent and efficacious choice for their treatment. |

| 9 | Ziping Huang et al. | Pathological neuroimaging | Assigned with stroke lesion | 11 subjects with pathological abnormality | Frontal lobe | Anode-FPz, Cathode-Oz | V 3.2.3 V 4.0 | Mean absolute difference = 27.98% among 11 subjects for E- field strength. | Study focuses on comparison for choosing various EF modelling pipeline with pathological abnormality. |

| 10 | Eva Mezger et al. | Brain Glutamate levels and resting state connectivity. | Healthy controls | 25 subjects (12- women & 8- men) | Pre-frontal cortex | Anode-F3, Cathode-F4 | V 2.0 | Activated voxels (mean=7620, sd=1676) compared to men (mean=3141, sd=1968) | Differences in concentration of Glu levels between male and female participants. |

| 11 | Athena Stein et al. | Traumatic brain injury | Healthy controls (HC), mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), severe traumatic brain injury (svTBI). | 43 patients (17- HC, 17- mTBI, 9- SvTBI) | Frontal lobe (DLPFC) | Anode-F3, Cathode-F4 | V 3.2 | HC- 0- 0.41 V/m, mTBI- 0- 0.71 V/m, svTBI- 0- 0.83 V/m. | The limited capability of T1 anatomical scans to detect white matter injury and microstructural damage. |

| 12 | Silvie Baumann et al. | Anorexia nervosa (AN) | Ages of 18 and 65 with the diagnosis of AN | 43 inpatients with AN, active (n = 22), sham (n = 21). | Left DLPFC | Anode-F3, Cathode-Fp2 | V 3.2 | 0- 0.368 V/m | tDCS has the potential to offer valuable assistance to individuals dealing with enduring body image concerns or obsessive calorie control behaviors, which are crucial factors in achieving remission. |

| 13 | Hamed Ekhtiari et al. | Drug cues | Diagnosed with methamphetamine use disorder (MUD) in the last 12 months | Sixty participants (all-male, mean age ± SD= 35.86 ± 8.47 years ranging from 20 to 55) | Right DLPFC | Anode-F4, Cathode-Fp1 | V 3.2 | 0- 0.35 V/m | The study revealed significant changes in brain activity over time among different groups when analyzing task-based fMRI data. The active stimulation group, which received tDCS, displayed increased functional activity. This increase in brain activity was strongly influenced by the individual effects of tDCS-induced executive functions, suggesting that tDCS played a regulatory role during cue exposure. |

| 14 | Dayana Hayek et al. | Cognitive enhancement | Healthy | 106 Participants, 50–82 years, mean age: 67 years, SD : 7 years | Inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), Sensorimotor (M1), Temporoparietal (TP) | Study- 1- A/C- FC5/Fp2 Study- 2- A/C- C3/Fp2 Study- 3- A/C- T6/Fp1 Study- 4- A/C- T6/Fp1 Study- 5- A/C- Cp5/Fp2 | V 3.2 | 0- 0.2 V/m | Individuals carrying alleles that have been previously associated with lower cognitive abilities, such as the Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT) allele, displayed a stronger behavioral response to tDCS. |

| 15 | SajjadAnoushiravani et al. | Sports performance | Professional gymnasts | 20 Participants (mean age=21.05±2.04) | Premotor cortex | Premotor stimulation- Two anode- Two cathode configuration (A1/A2- C3/C4) - (C1/C2- Fp1/Fp2). Cerebellar stimulation- (A1/A2- O9/O10) - (C1/C2- Fp1/Fp2). | V 3.2.3 | 0- 0.71 V/m | Stimulating the premotor cortex had a more significant effect on enhancing peak performance, while cerebellar stimulation specifically improved performance in the straddle lift to handstand test, emphasizing strength and coordination. |

| 16 | Kevin A. Caulfield et al. | Working memory improvement | Healthy | 28 HC (15 women, mean age = 73.7, SD = 7.3), active 2 mA (N = 14) or sham (N = 14). | DLPFC | Anode-F4, Cathode-F3 | V 3.1.1 | 0- 0.40 V/m | Increasing the intensity of tDCS in DLPFC has a more pronounced positive effect on working memory. |

| 17 | M. A. Bertocci et al. | Bipolar disorder | Bipolar Disorder type-I (remitted: >2 months euthymic and not psychotic. | Bipolar Disorder (n = 27), HC (n = 31) | Left vlPFC | Anode-Contralateral shoulder, Cathode-F7 | Not mentioned. | (- ) 0.15- (+) 0.15 V/m | These findings provide valuable proof of concept for the potential use of cathodal tDCS over the left vlPFC as an intervention for Bipolar Disorder. |

| 18 | Luise Victoria Claaß et al. | Working memory performance | Healthy | n= 36, s (mean age=26.97 years, SD: 3.53, 18 women) | L-DLPFC | Anode-F3, Cathode-Super orbital area | V 2.1 | 0 – 0.15 V/m | a-tDCS (Anodal tDCS) applied on L-DLPFC decreases functional connectivity with parietal cortex. |

| 19 | Hafez Teymoori et al. | Physical, psychological, cognitive performance. | MNI 152 head model | n = 1, MNI head model | Primary motor cortex (PMC) / L-DLPFC. | Anode-F3, Cathode-AF8 (L-DLPFC) Anode-Cz, Cathode-Left shoulder (PMC) | V 4.0.0 | 0 – 0.4 V/m | Positive effects were observed in various aspects, including the participants' rating of perceived exertion (RPE), electromyographic (EMG) activity of the vastus lateralis (VL) muscle, emotional valence, perceptual responses (measured using the circumplex model of affect), and cognitive function with a-tDCS on L-DLPFC. |

| 20 | Adriana Costa-Ribeiro et al. | Parkinson’s disease | Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease | n = 56, with diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. | L-DLPFC, Right contralateral supraorbital frontal cortex | Anode-F3, Cathode-Fp2 | V 2.1 | On-going clinical trial. | On-going clinical trial. |

| 21 | Marko Živanović et al. | Associative memory | Healthy | HC (n=40) 22–35 years of age (25.15±3.66 years, 25 females) | Posterior parietal cortex (PPC) | Anode-P3, Cathode-Contralateral cheek | V 3.1.6 | 0 – 0.321 V/m | tES techniques had a positive influence on short-term AM performance. Anodal tDCS was particularly effective when the memory demand was relatively low, whereas theta-modulated tACS and theta-modulated oscillatory stimulation (otDCS) were more beneficial in situations where the memory load was high. |

| 22 | Fenne M. Smits et al. | Stress regulation | Healthy | HC- (n=79) | R-DLPFC | Anode: F4, Cathode: behind C2 | V 3.2.3 | 0 – 0.5 V/m | tDCS had a short-term positive effect on emotional working memory performance, but this effect was limited to the early stages of the training. |

| 23 | Tulika Nandi et al. | Neurotransmitter quantification | Healthy | Left primary motor cortex (M1, 3 studies, n = 24) or right temporal cortex (2 studies, n = 32) | Lateral occipital complex, | Anode: lateral occipital complex Cathode: supra-orbital ridge | V 3.2 | 0 – 0.25 V/m (M1) 0 – 0.27 V/m (Temporal cortex) | Study has revealed a significant link between the strength of the electric field (E-field) in the MRS voxel of the primary motor cortex (M1) and a reduction in Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels. |

| 24 | Ahsan Khan et al. | Cognitive enhancement | Healthy | HC- (n= 20) (15 males- 5 females) | DLPFC | Anode: Fz, Cathode: cheek | V 3.0.1 | 0 – 0.43 V/m | tDCS stimulation successfully reached and influenced deep brain structures, particularly the cingulate, altering its activity. Decrease in the resting-state functional connectivity between ACC and subcortical brain regions both during and after the stimulation period. |

| 25 | Heiko Pohl et al. | Episodic Migraine Prevention | Healthy | HC- (n= 28) | Visual cortex | Anode: Oz, Cathode: Cz | V 2.1 | 0 – 0.2 V/m | Lowers the number of monthly migraine days upon the tDCS stimulation on visual cortex. |

| 26 | Laura C. Rice et al. | Healthy | Healthy | 43 participants (15 males, 28 females; 23.3 ± 3.0 years old | Parietal cortex | Anode: Right parietal cortex Cathode: right jaw bone | V 2.1 | 0 – 0.313 V/m | The behavioral task performance and the patterns of activation relevant to the task are influenced differently by distinct sub regions of the cerebellum involved in both sensorimotor and cognitive functions. |

| 27 | Vahid Nejati et al. | Verbal Fluency in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ADHD | Children with ADHD | n = 37, Clinically diagnosed with ADHD. | DLPFC, vmPFC | Anode: F3, Cathode: Fp2 & vice versa. Anode: F4, Cathode: Contralateral arm, Anode: F8, Cathode: Contralateral arm | Not mentioned. | 0 – 0.563 V/m, 0 – 0.544 V/m | The research findings suggest that stimulating the left (DLPFC) with anodal stimulation leads to better performance in phonemic fluency tasks, whereas anodal stimulation of the right DLPFC and right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) enhances performance in semantic verbal fluency tasks. |

| 28 | Kilian Abellaneda-Pérez et al. | Cognitive enhancement | Healthy | n = 31, HC, ([mean age ± standard deviation (SD), 71.68 ± 2.5 years; age range, 68 – 77 years; 19 females; years of education mean ± SD, 12.29 ± 4.0 years) | Front parietal, Posteromedial cortex | Frontoparietal cortical overactivity (C1) (AF7, F4, FC5, P3, P4, P7, P8 and Cz) , Posteromedial cortex (C2) (AF3, C3, C4, F4, FC6, Fpz, Oz and Cz) | V 3.0.7 | 0 – 0.1 V/m, | Findings underscore the effectiveness of multifocal tDCS procedures in altering neural functioning during aging as demonstrated by changes in rs-fMRI data. The observed modulation aligns with the spatial distribution of the electric current simulated in the brain. |

| 29 | Eva Mezger et al. | Schizophrenia and left frontal lesion | Healthy, Non-lesioned Schizophrenia patient, Schizophrenia patient with morphological abnormalities. | n = 3, HC, Schizophrenia with non-lesioned and morphological abnormalities | L-DLPFC, Left temporoparietal junction. | Anode-F3, Cathode-Tp3 | V 2.0.1 | Peak electric fields HC - 1.114 V/m Non-lesioned Schizophrenia patient – 0.76 V/m Schizophrenia patient with morphological abnormalities – 0.942 V/m. | E-field simulations indicated a comparable current distribution to a non-lesioned schizophrenia patient but with lower peak densities than those observed in a healthy control group. |

| 30 | Roderick P.P.W.M. Maas et al. | Skin cerebellar distance & morphometric posterior fossa parameters | Healthy | n = 37, Healthy subjects | Vermis and hemispheres of the anterior and posterior lobe | Anode-Iz, Cathode-Fpz | V 3.0.6 | 0 – 0.5 V/m | Apart from the distance between the skin and the cerebellum, variations in the structure of the posterior fossa, particularly the angles of the pons and cerebellum, contribute to explaining some of the fluctuations in the strength of the electric field induced by cerebellar tDCS. Moreover, when applying tDCS to the central region of the cerebellum, using a reference electrode placed outside the head is linked to reduced field strengths and improved precision in targeting the field compared to using electrodes on the head. |

| 31 | Naifu Jiang et al. | Chronic low back pain | History of nonspecific (Lower back pain) LBP for more than 3 months | n = 60, with LBP, Age 18-65 years | Left central lobe | Anode-C3, Cathode-Contralateral supraorbital area | V 2.1.2 | 0 – 0.817 V/m | Decrease in pain intensity with no significant alteration in back muscle activity. |

| 32 | Carys Evans et al. | Current direction analysis | T1 weighted MRI scans of healthy subjects | n = 50, T1-weighted MRI from human connectome project (HCP) | Motor cortex | Posterior-anterior (PA) montage (A- CP3, C- FCz), Medio-lateral (ML) montage (A- CPz, C- FC3), conventional montage (A-C1, C- Fp2) | V 3.2 | PA- 0.218–0.785 V/m, ML- 0.209–0.606 V/m, conventional - 0.129–0.431 V/m | Position of electrodes can be optimized and determined to get maximum current radially inward or outward for analysis of effects of tDCS in individual. |

| 33 | Valentina Alfonsi et al. | Sleepiness and vigilance | Healthy | n = 33, (12- males, 11- females, age – 24-37 years , mean age 29.73 ± 3.44 years | Frontal lobe | Anode-F4, Cathode-F3 | V 2.1 | 0- 0.8 V/m | tDCS to the frontal cortical regions can serve as an effective method to counteract the rise in the tendency to sleep and the decrease in alertness in individuals who are grappling with elevated levels of daytime sleepiness. |

| 34 | Ilse Verveer et al. | Analysis of impulsivity | Healthy | n = 30, 7- Males, 16- Females with Right handed and aged between 18-55 years | Pre-frontal cortex | HD-tDCS, A –Fz, C - (Fp1, Fp2, F7, and F8) | V 2.0 | 0- 0.35 V/m | HD-tDCS can alter the impulsivity by modulating neurophysiological components. |

| 35 | Parisa Banaei et al. | Cognitive enhancement under Hypoxic condition | MNI 152 standard head model | Standard head model | Primary motor cortex, L-DLPFC | Anode-Cz/F3, Cathode-Fpz, AFz | V 4.0.0 | 0- 0.3 V/m | Improves cognitive endurance performance in hypoxia. |

| 36 | Rémy Bation et al. | Obsessive compulsive disorder | Subjects with OCD symptoms defined by Yale-brown obsessive compulsive score (YBOCS) | n= 21, right handed, duration of illness (22.9 mean), mean age – 44.8 | Right cerebellum, Orbitofrontal cortex | Anode-Right cerebellum , Cathode-Fp1 | V 2.0.1 | 0 – 1 V/m | Non-effective outcome of tDCS treatment with the anode-cathode placement on Right cerebellum and Orbitofrontal cortex. |

| 37 | Ghazaleh Soleimani et al. | Electric field patterns upon tDCS stimulation. | Methamphetamine use disorder (MUD) | n= 66, mean age standard deviation (SD)=35.86±8.47 years ranges from 20 to 55 | DLPFC | Montage-1 (A- F4, C- Fp1) Montage-2 (A-F4, C-F3) | V 3.0.8 | 0- 0.6 V/m | The study suggests that understanding these network-level effects may clarify the extent of tDCS impact on the brain and proposes a method for future research using group-level analysis of brain networks to study tDCS effects and variability due to individual differences and electrode placement. |

| 38 | Wang On Li et al. | Time perception | Healthy | n = 70, Healthy | R- DLPFC, Right cerebellum | R-DLPFC (A-FC6, C- FC5) | V 2.1.1 | 0- 0.39 V/m | There is a cross-relation between attention and subjective time perception during and after the tDCS stimulation. |

| 39 | Andrés Molero-Chamizo et al. | Variability in E-field for different montage selection | Standard head model | n=1, Standard head model | M1- Motor cortex, DLPFC, Posterior parietal cortex - PPC | 20 Different positions for anode and cathode (Refer | V 2.1 | 0.19- 0.514 V/m Maximum electric field strength | SimNIBS offers reliable results for electric field strength when compared to its counterpart COMETS in standard head model. |

| 40 | Marie-Anne Vanderhasselt et al. | Cognitive control | Healthy | n = 35, Healthy | R-DLPFC | Anode-F4, Cathode- Contralateral supraorbital area | V 4.0.0 | 0 – 0.531 V/m | Applying tDCS to the right PFC led to decreased resource allocation and a decline in cognitive performance in both proactive and reactive control modes. |

| 41 | Utkarsh Pancholi et al. | Change in electrode parameters | Cognitively Normal | n = 1, Cognitively normal | DLPFC | Anode-F3, Cathode-F4 | V 3.2.6 | 0.264 – 0.308 V/m | Shape and size of the electrode changes electric field strength and focality in a single subject. |

| 42 | Mohsen Mosayebi-Samani et al. | Transferability of c (Cathodal)-tDCS from M1 to PFC. | Healthy | n = 18, Healthy, (11- males, 7- Females) | Left motor cortex, left prefrontal cortex | M1-stimulation (A-C3, C- contralateral supraorbital region), PFC stimulation (A-F3, C- contralateral supraorbital region) | V 3.2.3 | 0 – 0.15 V/m | The results indicate that low- and high-dosage tDCS applied to the motor cortex led to a reduction in the early positive peak of TMS-evoked potentials (TEP) and MEP amplitudes. However, a medium dosage of motor cortex tDCS showed an enhancement in amplitude. In contrast, prefrontal tDCS, regardless of dosage, consistently reduced the amplitudes of the early positive TEP peak. |

| 43 | Lynn Marquardt et al. | Dichotic listening | Healthy | n= 32, (18 male/14 female) was 26 ± 4.8 years (range = 20–39). | L-DLPFC, Temporo-parietal cortex (TPC) | Anode-CP5, Cathode-AF4 | V 2.1.2 | M (mean) = 0.77 ± 0.144 V/m, 99% of Peak electric fields | tDCS showed minimal to negligible impact on dichotic listening, glutamate and glutamine (Glx) levels, and functional activity. |

| 44 | Silvia Oliver-Mas et al. | Post-COVID fatigue | COVID patients | n = 47, 45 ± 9 years old, 78% Females, 20 ± 6 months after the detection of COVID virus infection | L-DLPFC | Anode-F3, Cathode- Contralateral supraorbital region | V 4.0.0 | 0 – 0.3 V/m | In post-COVID situation, tDCS could play a vital role to for potential benefit in physical fatigue upon stimulation on L-DLPFC. |

| 45 | Fabio Masina et al. | Behavioral and neurophysiological analysis | Healthy | n = 30, (15 males and 15 females) Age- 19- 30 year old, (mean age=23.4, standard deviation (SD)=1.9; mean education=16.2, SD=1.3) | Fronto-parietal lobe | Anode-C3, Cathode- Contralateral left shoulder HD-tDCS- Anode- C4, Cathode- FC2, FC6, CP2, CP6 | V 3.2 | Conventional montage: Peak electric fields – 0.366 V/m, HD-tDCS- Peak electric fields- 0.225 V/m | HD-tDCS resulted in a decrease in alpha power for individuals with lower baseline alpha levels, while Conventional tDCS led to a reduction in beta power for those with higher baseline beta levels. Conventional and HD-tDCS had unique effects on cortical activity. |

| 46 | Akihiro Watanabe et al. | Early dexterity skills | Heathy | n = 70, Healthy participants, aged 20–30 years | L-DLPFC | Anode-F3, Cathode- Fp2 | V 3.2 | 0 – 0.4 V/m | tDCS can significantly improve early dexterity skill upon left DLPFC. |

| 47 | Anant B Shinde et al. | Cerebral blood flow and motor behavior | Healthy | n = 32, 15-Males, 17- Females, Mean age: 34.2 (SD: 13.5) | Right precentral gyrus, supra-orbital region, left precentral gyrus | Unihemispheric montages (A-C4, C- Fp1) Bihemispheric Montages (A-C4, C- C3) | V 2.1 | Not mentioned | At an increased dosage and regardless of its polarity, tDCS has a beneficial impact on a broader array of sensorimotor regions. |

| 48 | Maria Carla Piastra et al. | Chronic stroke volume conductor head models | Stroke patients | n =16, Chronic stroke patients | Primary motor cortex | Ispi-lesional primary motor cortex (A- C3, C- Fp2), Contra-lesional primary motor cortex (A- C4, C- Fp1) | V 3.0 | 0.43 – 1.29 V/m | Chronic stroke patients having lesion in the brain carries varied conductivity values so as electric field strength. Estimation of lesion conductivity values helps for optimization of electrode location. Focality and dose parameters to achieve desired E-field values. |

| 49 | P. Šimko et al. | Cognitive training | Healthy aged people | n = 25, 17- women, 8 – men, Mean & SD : (68:84 ± 4:65 years old | Right middle frontal gyrus (MFG), Right superior parietal lobule (SPL) | Bi-frontal montage – (A- F3, C – Fp2), Right Frontoparietal montage – (A- Fp2, C- P4) | V 3.0 | Not mentioned | The combined tDCS and cognitive training approach appeared to promote greater functional connectivity between certain brain regions belonging to the frontoparietal control network, particularly on the left side of the brain. This enhanced connectivity could be one of the mechanisms responsible for the observed improvement in cognitive performance. |

| 50 | Davide Perrotta et al. | Stroop errors analysis | Healthy | n = 12, 6 –Males, 6- Females, Cognitively normal and healthy subjects | Inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) , DLPFC | Experiment-1, (A- Between T4-Fz, C- Between F8-Cz) Likewise 3 more experiments with varying electrode locations to analyze effects of tDCS | V 3.2 | 0 – 0.372 V/m for experiment- 1, Please refer | Study indicated that when anodal stimulation was applied (anodal stimulation typically involves an increase in neural excitability), it led to a reduction in errors during the task. |

| 51 | Nadine Schmidt et al. | Memory and attention control | Healthy | n = 105, Healthy participants, 60–75 years of age | Right inferior frontal lobe (montage-1), left inferior frontal lobe (Montage-2), right superior parietal lobe Montage-3) | HD-tDCS, Montage-1 (Central anode: FC6), Montage-2 ((Central anode: FC5), Montage-3 (Central anode: P4), Cathode for all montages: 3.5 cm away from central electrode | V 3.2.6 | Study protocol, ongoing | Ongoing |

| 52 | Toni Muffel et al. | Sensorimotor performance | Healthy | n = 45, 12 females, 33- males, 60 to 80 years (mean age: 69.4 ± 4.9 years) | Primary somatosensory cortex | Anode: C3, Cathode: Contralateral orbit | V 2.1 | 0 – 0.15 V/m | Stimulation of the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) using anodal transcranial direct current stimulation (a-tDCS) has contrasting impacts on proprioceptive accuracy depending on an individual's age. Employing modeling techniques could aid in uncovering the intricate connection between tDCS protocols, brain structure, and the modulation of performance. |

| 53 | Matin Etemadi et al. | Cognitive and endurance performance | Endurance trained males | n= 14, Age (Mean ± SD, 23.78±4.28) | Primary motor cortex, DLPFC | M1- (A- Cz, C- Left shoulder), DLPFC (A- F3, C- AF8), | V 4.0.0 | 0 – 0.45 V/m | The application of tDCS to the M1 did not yield statistically significant effects for any of the measured outcomes. |

| 54 | Marco Esposito et al. | Arousal level analysis | Healthy | n = 18, mean [SD] age=23.7 [3.8] ; 10 females | Frontal lobe | Anode: F3, Cathode: Supraorbital area | V 3.0 | 0 – 0.201 V/m | tDCS directly influences neuron excitability by altering their membrane potential, it may be more sensitive to arousal levels than TMS. |

| 55 | Devu Mahesan et al. | Task shielding in dual tasking | Healthy | n = 34, 27- F, 7-M, Mean age: 22.4 Years | L-DLPFC | Anode: F3, Cathode: Fp2 | V 3.0 | 0 – 0.2 V/m | tDCS can enhance the protection of prioritized task processing, particularly in situations where susceptibility to interference between tasks is most pronounced. |

| 56 | Bettina Pollok et al. | Conscious error correction | Healthy | n = 21, M-9, F-12, Mean age (24.14 ± .62 years) | Left ventral prefrontal cortex (vPFC) | HD-tDCS, targeting vPFC at central electrode and four other electrodes as returning electrodes 3 cm from central electrodes | V 3.2.2 | 0 – 0.0881 V/m | Our brain processes and corrects timing errors differently depending on whether we are aware of them or not, and the left vPFC plays a pivotal role in addressing consciously perceived timing errors. |

| 57 | M. A Callejón-Leblic et al. | Computational analysis of E-field components | ICBM152 realistic brain model | n = 1, Brain model, MRI images from 152 heads | Motor cortex, DLPFC, visual cortex, Auditory cortex | M1- (A-C3, C-RSOA), M2- (A- F3, C-RSOA, M3- (A-Oz, C-Cz), M4- (A-T7, C-T8) | Not mentioned | 0 – 1 V/m | Study finds a consistent trend where tangential electric fields are prominent over the brain's ridges (gyri), and normal electric fields are prevalent in the grooves (sulci). This pattern is somewhat consistent across different ways of placing electrodes on the brain. |

| 58 | Elias Boroda et al. | Augmentation of cortical plasticity | Healthy | n = 22, 8-F, 14-M, mean age- 24.9 years, | Primary auditory cortex, frontal lobe | Anode: (T7 & T8), Cathode: (Fp1 & Fp2) | V 2.1.1 | 0 – 0.6 V/m | tDCS can be a useful tool for intentionally modifying plasticity, which is the brain's ability to change and adapt. |

| 59 | Sarah Aronson Fischell et al. | Nicotine Withdrawal Syndrome | Healthy | n = 43, (Smokers: n= 15, Non-smokers: n = 28), Age: 18 to 60 Years | L-DLPFC, Right (R) vmPFC | M1-Anode: L-DLPFC, Cathode: R-vmPFC, M2- Anode: L- R-vmPFC, Cathode: DLPFC (Where R-vmPFC (Right supraorbital ridge and L-DLPFC (F3) | V 3.0 | 0 – 0.3 V/m | tDCS can affect important brain networks associated with nicotine withdrawal syndrome, which may provide a mechanistic rationale for exploring tDCS as a therapeutic tool in the field of psychiatry. |

| 60 | Carmen S. Sergiou et al. | Aggressive behavior | Alcohol and/or cocaine substance use disorder, sentenced for a violent offense | n = 50, All males participants, Mean age: 37.40 years | vmPFC | Anode: Fpz, Cathode (n=5) : AF3, AF4, F3, Fz and F4 | V 3.2 | 0 – 0.25 V/m | Research revealed increased connectivity in the frontal brain regions, especially in the alpha and beta frequency bands, as a result of HD-tDCS. This suggests that HD-tDCS may have the potential to enhance synchronicity in the frontal brain areas, contributing to our understanding of aggression and violence. |

| 61 | Gaurav V. Bhalerao et al. | Comparative analysis of E-field modelling platforms | Healthy | n = 32, 21- males ( Age = 26.09 ± 4.99 years) , 11- females (Age = 28.09 ± 5.99 years) | Fronto-temporal | Anode: AF3, Cathode: CP5 | V 2.1.2 | 0.01 – 0.6 V/m | There is no correlation among various E-field modelling platforms for stimulation outcomes. E-field characteristics depends on applied algorithms and patient data. |

| 62 | Megan E. McPhee et al. | Pain modulation | Diagnosed with chronic back pain | n = 11, Aged between 18-60 years old with chronic back pain | Medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) | HD-tDCS, Central anode: Fz, Four returning cathode: Fp1, Fp2, F7, F8 | Not mentioned | 0 – 0.4 V/m | Research indicates that applying active tDCS to the mPFC did not yield any significant impacts on pain relief mechanisms or on various psychophysical assessments, clinical features of lower back pain (LBP), or psychological traits. |

| 63 | Caroline R. Nettekoven et al. | Visuomotor adaptation | Healthy | n = 27, 17- Females (Aged between 18-32 years) | Right cerebellar cortex | Anode: Right cerebellar cortex, Cathode: Right buccinator muscle | V 3.2.3 | 0 – 0.3 V/m | The stimulation had no impact on memory retention throughout the entire experiment. |

| 64 | DariaAntonenko et al. | Cognitive training | Non-demented subject | n = 56, Aged 65-80 years, | L-DLPFC | Anode: F3, Cathode: Fp2 | V 3.1 | Mean electric field 0.09 – 0.15 V/m | There is no immediate effects of active tDCS stimulation in cognitive training. |

| 65 | Toni Muffel et al. | Sensorimotor functions | Diagnosed with mild to moderate upper extremity hemiparesis | n = 24, 16 males, mean age: 60.2 ± 12.4 years, 8-Females | Ipsilesional M1 hand area | Anode: C3/C4 Cathode: Fp2/Fp1 | V 2.1 | 0 – 0.15 V/m | Significant changes were observed in performance caused by tDCS, with the extent of these changes varying based on the specific task and the configuration of tDCS applied. |

| 66 | Daria Antonenko et al. | Validation of E-field simulation with neuromodulation | Healthy | n = 24, 12 females, mean age: 25 ± 4 years, 12-Males | Left somatomotor (SM1) cortex | Anode: C3 Cathode: Right supraorbital area | V 2.0 | 0 – 0.2 V/m | Decrease in GABA levels and an increase in SMN (Sensorimotor Network) strength occurred when using both anodal and cathodal tDCS, in comparison to a sham tDCS |

| 67 | Kai Yuan et al. | Functional connectivity in chronic stroke patients | Chronic stroke patients | n = 25, 7 – males, age = 61.8±6.9 years | Ipsilesional primary motor cortex (iM1), contralesional supraorbital ridge (cSOR) | Anode: C3/C4 Cathode: Fp1/Fp2 | V 3.2.0 | 0 – 0.6 V/m | Applying anodal tDCS to the primary motor cortex (M1) on the same side as the lesion (ipsilesional) enhances the connectivity of the sensorimotor network on that side in individuals with chronic stroke, and the strength of the personalized electrical field forecasted the functional improvements observed. |

| 68 | Shahrouz Ghayebzadeh et al. | Cognitive enhancement in female sport referees | Female referees | n = 24, aged 18–38 years old (mean: 28 ± 3.25) | R-DLPFC | Anode: F4 Cathode: Fp1 (a-tDCS), Anode: Fp1 Cathode: F4 | V 4.0.0 | 0 – 0.3 V/m | Applying anodal tDCS to the R-DLPFC could potentially enhance the ability of female sports referees to make delicate and precise decisions. |

| 69 | Zhenhong He et al. | Depression | Depressive mood (DM) | n= 190, 96 with high DM and 94 with low DM | Right VLPFC | Anode: F6 Cathode: Fp1 | Not mentioned | 0 – 1 V/m | The activation of the RVLPFC using tDCS appeared effective in regulating social exclusion than in managing individual negative emotions. This impact of tDCS on the regulation of social exclusion was particularly evident among individuals with low DM as opposed to those with high DM. |

| 70 | Asif Jamil et al. | Aftereffects of tDCS | Healthy | n = 29, 16 – males, mean age 25.0 ± 4.4 years | Motor cortex | Anode: abductor digiti minimi muscle (ADM) hotspot , Cathode: Right frontal orbit | V 2.1.2 | 0 – 0.5 V/m | Variability in current intensity of tDCS causes varying effects on cortical blood flow resulting altered effects on motor cortex excitability. |

| 71 | Amber M. Leaver et al. | Brain network modulation | Mostly healthy | n = 64, Females -34, Males – 30, | DLPFC, Lateral temporoparietal area (LTA), Superior temporal cortex (STA) | DLPFC (A-F3, C- F8), LTA (A- CP5, C – FT8), STA (A- T7, C- T8) | V 3.0 | 0 – 0.4 V/m | Active tDCS can influence brain network connectivity most strongly when higher electrical currents are applied. |

| 72 | Martin Panitz et al. | Behavioral adaptation, Cognitive enhancement | Healthy | n = 61, Anodal stimulation group : 15 female, age: M = 26.3, SD = 4.1, range = 20–35 years, Cathodal stimulation group: 15 female, age: M = 27.0, SD = 3.2, range = 22– 38 years | Medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) | Anode: MNI coordinates of mPFC, Cathode: Cz | V 3.2.1 | 0 – 0.2 V/m | Anodal tDCS could directly influence the ability to display flexible, adaptive behavior and specifically impact learning about the unchosen choice option |

| 73 | Yuanbo Ma et al. | Chronic Ankle Instability (CAI) | Ankle pain and sprain | n = 30 | Primary sensorimotor cortex | HD-tDCS, Central anode : Cz, Four returning cathode: C4, Pz, C3, Fz | Not mentioned | 0 – 0.18V/m | Study suggests that HD-tDCS has potential as an additional tool in rehabilitation exercises for younger adults with CAI, indicating that further research in this area is warranted. |

| 74 | KevinA. Caulfeld et al. | Electrode parameters and its effect on E-field | Healthy | n = 200 | Multiple targets for central and frontal lobe, see | Anode : C3 Cathode: Fp2 (M1-SO), Central anode: C3, Four cathodes: 2.9 cm from central electrode (HD-tDCS), Anode: CP3, Cathode: FC3 (Anterior posterior pad surround- APPS) | V 3.2.3 | 0 – 1 V/m | APPS-tDCS, which involved situating electrodes both in front of and behind the target brain region, it resulted in more than twice the intended electric field strength and minimized unintended effects, all while using the same 2 mA stimulation intensity as traditional electrode placements. |

| 75 | Adam Wysokinski et al. | Brain-fog, cognitive impairment | Cognitive dysfunction related to COVID-19 infection | n = 1, MDD after COVID-19 infection | DLPFC | Anode: F3, Cathode: F4 | V 3.1.2 | 0 – 0.415 V/m | Combining tDCS with computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation could serve as a viable treatment choice for individuals experiencing COVID-19-induced brain fog. |

| 76 | Jana Klaus et al. | Intracranial variability in electric fields | Healthy | n = 20, 8 - female, mean age=26.6 years, range: 21– 38 years | Right posterior cerebellum | Conventional montages: Frontopolar (A- I2, C- Right cheek), Buccinator: (A- I2, C- Fp1), For alternative montages see | V 2.1 | 0 – 0.8 V/m for conventional montages, For alternative montages see | Smaller electrodes placed closer together, which significantly enhance field focus in the cerebellum. Strength of the field varies between individuals, primarily based on the distance between the scalp and the cortex. |

| 77 | Desirée I. Gracia et al. | Post COVID Anosmia | Loss of smell after COVID-19 infection | n = 25, 12 females, 13 males (aged 19 to 55 years) | Olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, piriform cortex | Model 1: Anode electrodes, FP1 and FP2; cathode electrodes, P9 and P10. For other four models see | Not mentioned | 0 – 0.15 V/m | Neurostimulation suggested that individuals with lower olfactory assessment scores could potentially experience some improvement but not significant. |

| 78 | Elisabeth Hertenstein et al. | Creativity, Cognitive ability | Healthy | n = 90, 45 female, 45 male, mean age 23.8 ± 2.3 years | Inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) | Right IFG (Between crossing point between T4-Fz and F8-Cz), Left IFG (crossing point between T3-Fz and F7-Cz) Both right IFG and left IFG interchanged to anode and cathode) | V 3.0 | 0.003- 0.25 V/m | Stimulating the right prefrontal cortex with tDCS while deactivating the left prefrontal cortex has been linked to a boost in creativity. |

| 79 | Carmen S. Sergiou et al. | Aggressive behavior | Forensic patients with aggressive behavior, drug abuse | n = 50, Males, (mean age = 37.40 years, SD = 9.19 years, range: 22–62 years | Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex (vmPFC) | HD-tDCS, Anode: Fpz, Returning or cathode electrodes: AF3, AF4, F3, F4, and Fz | V 3.2 | 0 – 0.25 V/m | Multiple sessions of HD-tDCS, directed at the vmPFC, led to a decrease in aggressive behavior. |

| 80 | Sara Calzolari et al. | Motor network connectivity | Healthy | n = 49, mean age: 25 ± 4; 15 males, 34 females | Primary motor cortex | Experiment 1: (A- C3, C- Fp2), Experiment 2: (A- I2, C- right buccinator muscle) | V 4.0 | Experiment 1: 0 – 0.264 V/m, Experiment 2: 0 – 0.349 V/m | Significant and widespread spatiotemporal changes in the motor network during and after both M1- and cb-tDCS stimulation |

| 81 | Weiqian Sun et al. | Multi-layer skull modeling | Healthy | n = 1, Male, 25 Year old | Frontal and central lobe | Case 1 : Anode placed at the corners of (Cz, FCz, C1 and FC1.), cathode (Fp2), Case 2: Anode placed at the corners of (Cz, CPz, C2, and CP2.), cathode (Fp1) | V 3.2 | 0 – 0.6 & 0 – 0.8 V/m in case-1 and case-2 respectively | Addition of spongy bone in the typical 5-layer established head model gives more accurate and realistic electric field distribution. |

| 82 | Sean Coulborn et al. | Shifting of attention behavior, Cognitive domain | Healthy | n = 23, six males, aged 18–23; M = 19.83, SD = 1.34 | DLPFC, Right inferior parietal lobule (IPL) | Anode: P4, Cathode: Left cheek | V 2.1.0 | 0 – 0.587 V/m | Questioning about the effects of tDCS in self-generating cognitive processes. Study failed to prove or replicate the previous study dictating the positive effects of tDCS in self-generating cognitive process. |

| 83 | Rinaldo Livio Perri et al. | Cigarette craving | Smokers | n = 20, 10 for Active tDCS group (4 males, mean 35.1 ± 18.2 years), 10 for sham group ((1 male, mean 30.6 ± 16.5 years) | DLPFC | Anode: F4, Cathode: F3 | V 3.2 | 0 – 0.44 V/m | tDCS has positive effects for cessation of smoking cravings by tailored stimulation parameters. |

| 84 | M. Herrojo Ruiz et al. | Reward based motor learning | Healthy | n = 19, healthy participants | Fronto-polar cortex | Anodal tDCS: A- rPFC, C- Vertex | V 2.1 | 0 – 0.1 V/m | rFPC-tDCS enhances the ability of the motor system to adapt to changes in reward unpredictability, thereby expediting the process of learning from rewards in a motor context. |

| 85 | Joris van der Cruijsen et al. | Chronic stroke | Chronic stroke patients | n = 21, 6 months post-stroke at the time of inclusion, with initial hemiparesis | Motor cortex | Anode: C3/C4, Cathode: Fp1/Fp2 | V 3.2 | - 0.5 to 0.5 V/m | Failing to simulate tDCS in personalized head models results in lower and inconsistent electric field strength in stroke patients, which might impact the effectiveness of tDCS on clinical outcomes for both individuals and groups. |

| 86 | Benjamin Meyer et al. | Neuromodulation | Healthy | n = 42 | DLPFC | Anode: Fpz, Cathode: F4 | V 3.0 | 0 – 0.3 V/m | tDCS induces specific neural activity increases in subcortical regions of the dopaminergic system, particularly in the striatum. |

| 87 | Hannah McCann et al. | Ageing | Healthy | n = 6, Equal males and females | Motor cortex | Anode: C3, Cathode: AF4 | V 3.1.2 | 0 – 1.2 V/m | The most significant factor influencing the changes in peak field with age is the variation in skull conductivity. |

| 88 | Bettina Pollok et al. | Motor sequence learning | Healthy | n = 18, 24.83 ± 0.89 years (mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.)), 9- females, 9 – Males | Motor cortex | Anode: M1, Cathode: PFC | V 3.2.2 | 0 – 0.1 V/m | Left dPMC could be a viable target for non-invasive brain stimulation techniques in explicit motor sequence learning involving the right hand. |

| 89 | Mohammad Ali Salehinejad et al. | ASD | Autistic | n = 16, 8 boys, mean age = 10.07 ± 1.9 | Ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and temporoparietal junction (TPJ) | vmPFC: (A-Fpz, C- Neck) r-TPJ: (A-CP6, C- Neck) | V 2.1.1 | 0 – 0.65 V/m | Study’s results highlight that vmPFC activation, in comparison to r-TPJ, plays a more substantial role in comprehending and resolving Theory of Mind (ToM) issues in individuals with ASD. |

| 90 | E. Kaminsk et al. | Motor and cognitive enhancement | Healthy | n = 60, 30 Young adults (27.07 ± 3.8 years), 30 Old adults (67.97 years ± 5.3 years) | Motor cortex | Anode: On M1- motor cortex (MNI co-ordinates), Cathode: Fpz | V 3.1.2 | 0 – 0.2 V/m | tDCS can induce a brain state that enhances performance, particularly when it comes to acquiring explicit skills. |

| 91 | Yu-Chen Kao et al. | Medication adherence | Schizophrenia patients | n = 60, 20–65 years old | DLPFC | Anode: Between F3 and Fp1, Cathode: Between T3 and P3 | V 2.1.2 | Not mentioned | Short-term fronto-temporal tDCS has positive effects on how schizophrenia patients perceive their mental illness and adhere to treatment. |

| 92 | Oliver Seidel‑Marzi et al. | Motor fatigability | Healthy | n = 46, 13- foot ball, 12- hand ball and 21- Non-athletes players , Healthy individuals with no adverse medical history | Motor cortex | Anode: Cz, Cathode: Fz | V 3.0.6 | 0 – 0.30 V/m | Motor slowing (MoSlo) can be influenced through anodal tDCS over the M1 leg area in both trained athletes and non-athletes. |

| 93 | Karl D. Lerud et al. | Auditory memory modulation | Healthy | n = 14, 7- males, 7- females | Supramarginal gyrus (SMG) | Anode: Supramarginal gyrus, Cathode: Supraorbital area | V 2.1 | Not mentioned | The SMG serves as a crucial hub for temporary auditory memory, and this study highlights the capacity of tDCS to impact cognitive abilities. |

| 94 | Dominika Petríková et al. | Word retrieval (Cognitive enhancement) | Healthy | n = 136, sham tDCS (n = 45), anodal (n = 45) or cathodal tDCS (n=46). | Cerebellum | Anode: Cerebellum, Cathode: Right side of the neck | V 3.0 | 0 – 0.25 V/m | Anodal cerebellar tDCS improved the recall of words related in meaning within free-associative chains. Cathodal tDCS, while opposite in effect to anodal stimulation, did not show statistically significant results. |

| 95 | Mahsa Khorrampanah et al. | Optimization of stimulating electrode location | Standard head model | n = 1 , Head model | Motor cortex | Multiple montages and location of electrodes, See | V 2.1 | 0 – 0.536 V/m | The study demonstrates a significant increase in tDCS efficiency, nearly 2.5 times more effective in gray matter compared to High Definition (HD) montages, and almost 1.5 times more effective in comparison to the other inner layers. |

| 96 | Rasmus Schülke et al. | Schizophrenia spectrum disorder (SSD) | Patients with SSD | n = 19 | Parietal, Fronto-parietal and frontal lobe | Frontal (A- F3/F4), Parietal (CP3/CP4) | V 3.2.1 | 0 – 0.317 V/m | When tDCS was applied to the right parietal area, there was an increase in the influence of angle variations on how SSD patients perceived causality. |

| 97 | M.J. Wesse et al. | Hand motor skills | Chronic stroke survivals | n = 12, ≥ 18 years of age | Motor cortex | Anode: CB ipsilateral, Cathode: ipsilateral buccinator muscle | V 3.0 | 0 – 0.4 V/m | Stroke survivors with lower baseline motor abilities and sustained motor cortical disinhibition in the chronic phase benefited by Cerebellar (CB) -tDCS. |

| 98 | Anke Ninija Karabanov et al. | Motor activity | Healthy | n = 17, F=10, M-7 | Motor cortex | Anode: right primary motor hand area (M1-HAND), Cathode: Left supraorbital region | V 2.1 | 0 – 0.201 V/m | An individual's sensitivity to the neuromodulatory effects of TDCS on corticospinal excitability is influenced by various physiological factors. |

| 99 | Jana Klaus et al. | Verbal fluency | Healthy | n = 44 | Left prefrontal cortex | Anode: Between FC5 and C5, Cathode: Centre of the forehead | V 2.0 | 0 – 0.5 V/m | A single session of anodal tDCS to the left PFC does not lead to any noticeable enhancement in verbal fluency performance among healthy participants. |

| 100 | Darin R. Brown et al. | Alcohol use disorder (AUD) | Participants who expressed interest by involving in group alcohol treatment. | n = 68, active tDCS (n = 36) or sham tDCS (n = 32) | Right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) | Anode: Right IFG, Cathode: Left upper arm | V 2.1 | 0.2 – 0.5 V/m | The study revealed that both self-reported alcohol craving and the Late Positive Potential (LPP) in response to alcohol-related images decreased notably from before to after the tDCS treatment, but this was not the case for other types of images. The extent of the decrease in alcohol-related craving was linked to the number of Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP) group sessions attended. |

Applications of tDCS in various domains in 100 reviewed articles

Number of reviewed papers from 2019 to 2023.

Andrés Molero-Chamizo et al. administered five anodal tDCS sessions to the motor cortex of three stroke survivors and observed improvements in pain control and reductions in upper-limb spasticity, albeit with marked inter-individual variability 8. Paulo J. C. Suen et al. correlated simulated E-field strength with behavioral change in 16 patients with major depressive disorder receiving tDCS to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC); higher E-field intensity was inversely associated with negative affect in both regions and with depression scores in the left ACC, suggesting a mechanistic link that merits further study 9. A cross-diagnostic investigation reported diminished prefrontal E-field strength during tDCS in individuals with schizophrenia and, to a lesser extent, major depressive disorder, whereas patients with bipolar disorder showed no significant difference from healthy controls 10. Karin Prillinger et al. explored the feasibility, tolerability, and neural effects of tDCS in adolescents with autism-spectrum disorder, focusing on social and emotional functioning, and highlighted the modality’s therapeutic potential 11.

One study investigated the potential of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) to enhance motor learning in children with perinatal stroke (PS) by simulating tDCS-induced electric fields (EFs) with various electrode montages. The authors reported montage-dependent differences in EF strength and its relationship to underlying anatomy in children with arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) or periventricular infarction (PVI) compared with typically developing controls (TDC), thereby emphasizing the importance of individualized tDCS planning for future clinical trials 12. In efforts to optimize multichannel tDCS, Videira et al. showed that electrode spacing—particularly the anode-to-cathode distance—exerts the greatest influence on EF distribution, whereas the use of more than three cathodes produced no additional change in EF magnitude or direction. These findings inform efficient electrode placement, especially during concurrent tDCS-electroencephalography (EEG) recordings 13. Mizutani-Tiebel et al. assessed individual, MRI-derived electric fields (e-fields) during standard bifrontal tDCS in 74 participants with major depressive disorder (MDD), schizophrenia (SCZ), or healthy status. They identified significant differences in e-field strength between clinical and non-clinical groups, highlighting the need for individualized dosing in patient populations 14. Two separate randomized clinical trials targeted nicotine craving and relapse. tDCS applied to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) significantly reduced nicotine dependence and the likelihood of future smoking 15,16. In both studies, tDCS simulations performed in SimNIBS estimated EF strength and focality within the DLPFC under distinct stimulation parameters. Although SimNIBS provides fully automated head-tissue segmentation, its developers caution that accuracy may be compromised in the presence of structural brain pathology. Huang et al. addressed this limitation by assigning lesion-specific conductivity values and comparing the resulting EFs across different modeling platforms, including SimNIBS and ROAST 17. Because glutamate is the principal excitatory neurotransmitter, tDCS-induced currents may modulate its release and regulation, thereby altering synaptic plasticity. Mezger et al. combined EF simulations with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy to quantify glutamate concentrations and resting-state functional connectivity during tDCS 18. Additional findings were presented at the 2022 Neuroergonomics and NYC Neuromodulation Conference, but detailed results have yet to be published.

Athena Stein et al. conducted a comparative analysis of electric field simulations in children who were cognitively normal or had mild or severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) 19. They found no significant differences in electric field strength across groups, indicating that current delivery was comparable. In psychiatric disorders such as anorexia nervosa (AN) and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) has demonstrated therapeutic efficacy, reducing symptoms over multiple sessions. Studies 20,21 simulated electric field strength with SimNIBS on a standard head model and obtained 0.368 V/m for AN and 1 V/m for OCD. In a cue-reactivity paradigm for methamphetamine use disorder (MUD), an average electric field of 0.35 V/m was associated with modulation during cue exposure 22,23. Using the SimNIBS standard head models ‘ernie’ and MNI152, investigators estimated electric field strength to assess physiological and cognitive effects of tDCS applied to premotor areas and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) 24,25. In healthy young adults, no significant improvements in working memory were observed 26,27; however, Kevin A. Caulfield et al. suggested that reducing cortical electric-field variance may enhance outcomes 28. The DLPFC, located on the lateral aspect of the prefrontal cortex, is critical for executive functions such as planning, reasoning, and problem-solving. Five independent studies targeting cognitive enhancement with tDCS reported improved performance 29,30,31,32,33. These investigations used MNI coordinates and the international 10–20 EEG system to position the electrodes and simulated electric fields on standard head models for conceptualization.

In the realm of mood disorders, M. A. Bertocci et al. reported that applying cathodal tDCS over the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC) is an effective therapeutic intervention for bipolar disorder 34. Similarly, Zhenhong He et al. have shown that anodal tDCS over the right vlPFC reduces subjective emotional intensity and physiological arousal elicited by negative experiences 35.

Within psychotic disorders, amelioration of symptoms in schizophrenia and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders has been achieved by administering tDCS to the frontopolar cortex 36 and parietal lobe 37.

For impulse-control and behavioural disorders, Ilse Verveer et al. demonstrated the ability of dACC-targeted HD-tDCS to modulate neurophysiological indices of impulsivity 38. Carmen S. Sergiou and colleagues reported increased frontal connectivity within the alpha- and beta-frequency bands following HD-tDCS 39. In a separate study, the same group found that repeated HD-tDCS sessions applied to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) decreased aggression 40.

Regarding cognitive control, cognitive performance, and physical endurance, tDCS applied to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) has proven beneficial 41,42,43.

The parietal lobe contributes substantially to multiple components of memory processing. It participates in the encoding, consolidation, and retrieval of episodic memories—representations of specific events or experiences—and supports spatial memory, enabling individuals to navigate and retain the spatial configuration of their surroundings. Electrode montages that specifically stimulate the parietal cortex have been shown to improve associative memory, attentional control, and lexical retrieval 44,45,46. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) may also augment verbal fluency and diminish mind-wandering in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) 47,48. The sustained neuromodulatory effects of tDCS observed in cognitive rehabilitation indicate a promising therapeutic avenue both for post-COVID-19 cognitive impairment and for preserving cognitive health in older adults without dementia 49,50,51.

Computational modeling of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) entails simulating and analyzing the spatial distribution and physiological effects of electric currents delivered to the brain. This process typically employs computer algorithms and mathematical models to predict the electric field distribution, current density, and overall impact on neural activity within the targeted cortical regions. The overarching goal is to elucidate the potential physiological and cognitive outcomes of tDCS under various stimulation parameters, electrode montages, and individual anatomical variations. Consequently, computational modeling is indispensable for optimizing tDCS protocols and for clarifying the mechanisms underlying its neuromodulatory effects.

Numerous scholars have contributed to this field, frequently using SimNIBS to develop or test stimulation protocols. Carys Evans et al. simulated three T1-weighted MRI head models with ROAST and SimNIBS, highlighting the importance of simulation software in characterizing inward and outward current flow 52. Andrés Molero-Chamizo et al. used SimNIBS and the COMETS platform to simulate twenty typical electrode configurations, reporting no substantial differences in the resulting electric fields between the two tools 53. Utkarsh Pancholi et al. examined the influence of electrode size and shape, current intensity, and electrode gel on the simulated electric field and focality, observing a notable reduction in both metrics as electrode size increased 54,55. Similarly, M. A. Callejón-Leblic et al. targeted diverse brain regions and documented significant changes in electric-field strength and distribution, particularly in peak tangential and normal components 56.

In a methodological comparison, Gaurav V. Bhalerao and colleagues evaluated segmentation and head-modeling pipelines—SimNIBS Freesurfer-FSL (mri2mesh: SNF), SimNIBS headreco (CAT12: SNC), SimNIBS headreco (SPM: SNS), ROAST (RST), and ScanIP Abaqus (ABQ)—across thirty-two subjects and quantified the relative differences in mean electric fields within predefined regions of interest 57. Likewise, Kevin A. Caulfield and collaborators optimized electrode positioning (traditional vs. innovative), electrode size (larger vs. smaller), and inter-electrode distance (greater vs. lesser) to enhance electric-field magnitude and focality in the targeted cortex 58. Two additional investigations focused on improving electric-field characteristics through montage optimization, specifically by adjusting electrode positions and their spatial relationships 59,60.

Discussion

It is important to note that the computational analysis of therapeutic outcomes from both in vivo and in vitro transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) studies is increasingly important. In-silico platforms such as SimNIBS, ROAST, and COMET have streamlined these analyses by offering detailed models of cranial tissues and their electrical properties when exposed to direct current. SimNIBS, in particular, is more widely used than other simulation platforms. It can be used for predictive modelling with standard head templates in clinical trials to anticipate therapeutic efficacy at early stages 11,20,22,26,31,41,43,45,50. The increasing application of electric-field (E-field) analysis in SimNIBS entails systematic variation of stimulation parameters and the implementation of optimization algorithms. Such analyses forecast current distribution and focality within the target region. For instance, optimization algorithms have been applied to predict differential tDCS effects in cognitively normal (CN) individuals and in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or Alzheimer’s disease (AD) 1. Likewise, modifications in electrode size, shape, or conductive medium alter induced current density and clinical outcomes 54. SimNIBS also quantifies the normal and tangential components of the induced E-field during tDCS 56. Current-flow modelling allows estimation and optimization of inward and outward current orientations, thereby localizing zones of depolarization and hyperpolarization 52,53,106. E-field patterns vary across individuals, a phenomenon that can be systematically investigated with computational modelling 23,59. These models also enable comparison between SimNIBS and other in-silico platforms 57.

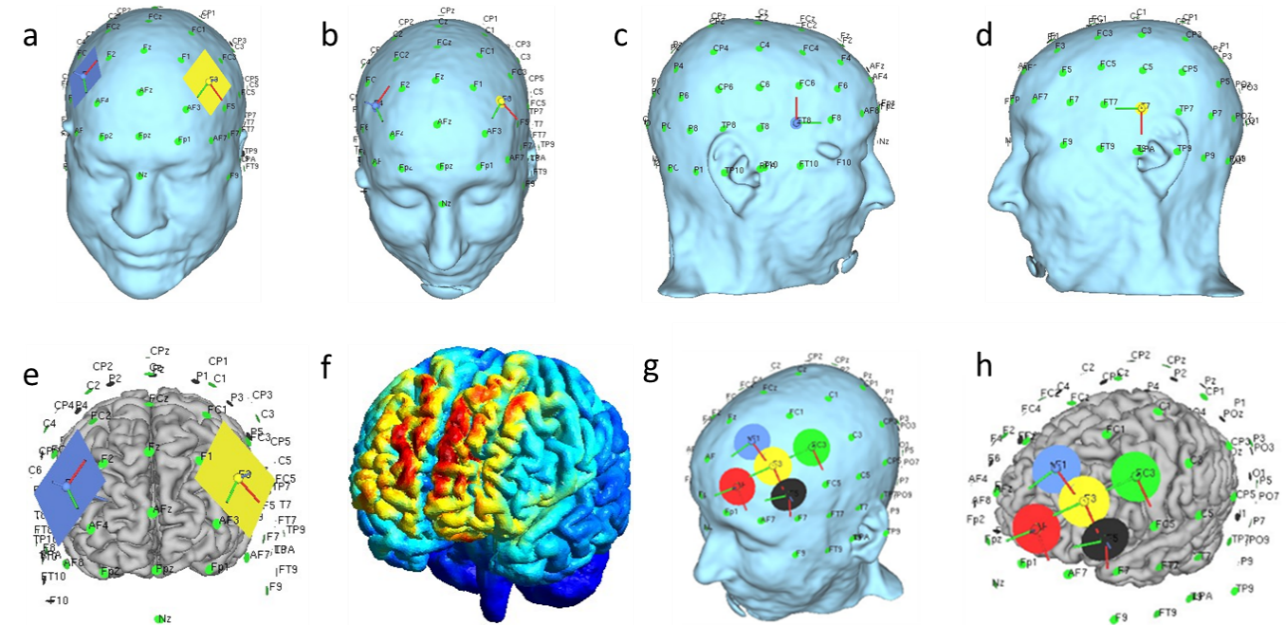

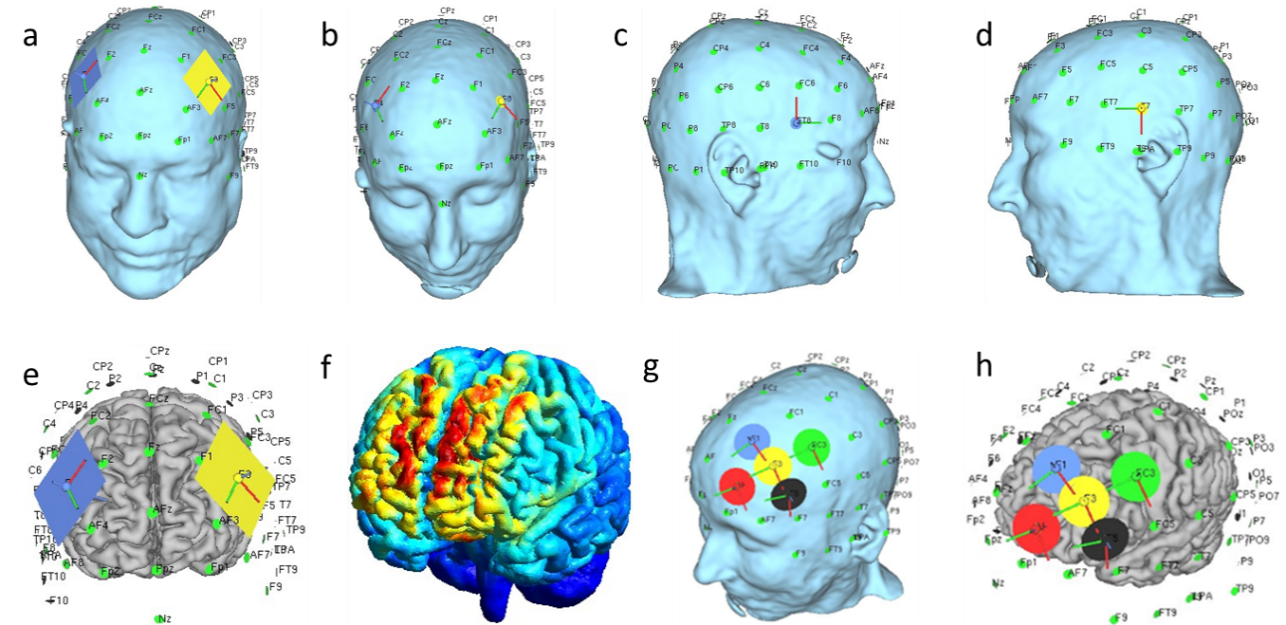

In this study, we identified the locations of the stimulating electrodes on standard or MRI-derived head models using the 10–20/10–10 EEG placement system and MNI-based target coordinates (

Illustration of tDCS montage and E-field. a) Typical bipolar placement of a rectangular electrode. b) Circular electrode placement. c) Anode placement on the right side of the head. d) Cathode placement on the left side of the head. e) Bipolar electrode placement indicating the interface with grey matter. f) E-field illustration of bipolar stimulation, with the heat map indicating field strength (red: maximum, blue: minimum). g) High-Definition tDCS (HD-tDCS) placement with a circular electrode array. h) HD-tDCS electrode placement indicating the interface with grey matter.

The electric field intensity is a very important parameter for tDCS, measured in V/m, and represents the strength of the electrical force acting on charged particles (ions) within brain tissue. This metric is critical because it modulates neuronal activity. The magnitude of the field determines the degree to which neuronal membranes become polarized or depolarized, thereby altering neural excitability. However, the relationship between field intensity and physiological outcome is complex; electrode size, placement, and inter-individual variability also contribute. In the present review we assessed the reported electric field intensity in each of the 100 articles examined and observed wide variability across studies and objectives. For example, A. Molero-Chamizo et al. used electric field modelling to reach a peak intensity of 0.36 V/m in a standard head model, aiming to modulate spasticity while accommodating inter-individual variability 8. Participants with schizophrenia or major depressive disorder displayed significantly lower e-field strength at the 99.5th percentile than healthy controls 10. Several studies evaluated the reliability of electric-field estimates by comparing software packages; SimNIBS showed greater reliability than COMET 53,57. Variations in tDCS current intensity produce differential effects on cortical blood flow, consequently modifying motor-cortex excitability 90.

The primary aim of this review is to demonstrate the influence of SimNIBS and its applicability in devising effective treatment regimens through predefined parameter selection and modeling. No significant limitations have been identified regarding the functionality or effectiveness of SimNIBS. The outcomes of the 100 reviewed clinical investigations are primarily affected by the sample size, the number of electrodes, the inter-electrode distance, inter-individual variability, electrode size and shape, electrode thickness, stimulation site, patient age, sex, and the conductivities of cranial tissues. Molero-Chamizo et al. reported on three stroke patients enrolled in a 9- to 15-month study that evaluated the therapeutic effect—specifically pain relief—after several sessions of tDCS 8. The small sample size is additionally concerning because pain was recorded only immediately before and after each of the five interventions, with no follow-up assessments.

In a separate study, Andreia S. Videira et al. investigated how inter-electrode distance and electrode number influence the induced electric field, illustrating E-field fluctuations in a standard brain/head model to quantify variability 13. Including additional subjects could introduce confounding factors, as the objective was solely to examine E-field variation attributable to electrode distance and number. Parisa Banaei et al. used standard, large, rectangular tDCS electrodes to simulate an optimal electric field (>0.20–0.25 V/m) 31. The goal of this simulation study was to replicate the desired electric field, necessitating deliberate selection of electrode dimensions, shape, and placement. However, the scarcity of electrical modeling tools for injured or lesioned brains and the ongoing challenges in T1 anatomical image reconstruction constrain such investigations. Eva Mezger et al. therefore recommended further research and development of reconstruction algorithms and field models for damaged brain structures in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders, including stroke rehabilitation 36.

Molero-Chamizo et al. employed SimNIBS and COMETS to test 20 tDCS electrode configurations with a finite-element approach, comparing the results and assessing inter-individual variability 53. Either a subject-specific realistic model is sufficient to evaluate inter-individual variability. Automated tissue segmentation of T1- and T2-weighted MRI data is a core component of SimNIBS. However, normal tissue contrast may be disrupted in pathological conditions such as stroke, tumors, traumatic brain injury, or neurodegenerative diseases 111. Such contrast alterations can lead to misclassification of CSF, edema, or necrotic tissue, and failure to model cavities or calcifications accurately. Complex pathological anatomies, including enlarged ventricles, cortical atrophy, or tissue displacement, are difficult for SimNIBS to mesh and simulate accurately, potentially resulting in erroneous electric field estimates 112. SimNIBS relies on literature-derived average values and therefore assumes static, isotropic tissue conductivities that may not reflect the altered, anisotropic, and dynamic properties of lesioned tissues under pathological conditions 113. Moreover, SimNIBS has not yet undergone extensive validation in clinical populations; limited evidence exists comparing simulated with measured electric fields or evaluating the impact of simulation-guided therapies in diseased brains 114.

Conclusion

In summary, SimNIBS has garnered considerable interest among neurophysicists, biomedical engineers, and other research professionals owing to its versatile functionality and robust computational capabilities. It provides accurate predictions of the spatial distribution and focality of the electric field prior to the administration of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), thereby preventing unintended stimulation and enhancing therapeutic outcomes. The peak or mean electric-field intensity generated during tDCS typically ranges from 0.5 to 2 V m⁻¹; however, these values are modulated by several variables, including applied current strength, electrode size and montage, and inter-individual anatomical variability. Such influences can be estimated with in-silico platforms such as SimNIBS. We identified 100 highly relevant research articles published between 2019 and 2023; an additional 611 publications may also contain information pertinent to the usability of this current-flow modelling platform.

The absence of standardized simulation methodologies continues to hamper tDCS modelling, leading to heterogeneous findings across studies. Future investigations should harmonize electrode montages, current intensities, and modelling parameters to improve reproducibility and enable cross-study comparisons. The development of best-practice guidelines, particularly for SimNIBS, is expected to enhance consistency and clinical applicability. While current head models accurately approximate current flow in healthy individuals, models for pathological conditions—especially stroke, epilepsy, and traumatic brain injury—require further refinement. Subsequent research should incorporate disease-specific anatomical alterations, such as lesions, atrophy, and abnormal tissue conductivities, to optimise clinical stimulation protocols and treatment planning. Finally, rigorous validation of computational simulations against experimental and clinical data remains imperative. Integrating patient-specific computational models with empirical measures, including neuroimaging (e.g., fMRI, BrainSuite) and electrophysiology (e.g., EEG), is anticipated to improve the predictive accuracy of tDCS models and facilitate their translation to clinical practice.

Abbreviations

A: Anode; ACC: Anterior cingulate cortex; ADHD: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AIS: Arterial ischemic stroke; AN: Anorexia nervosa; ASD: Autism spectrum disorder; AUD: Alcohol use disorder; C: Cathode; CAI: Chronic Ankle Instability; CAT: Computational anatomical toolbox; COMETS: Computation of Electric field due to transcranial current Stimulation; COMT: Catechol-O-Methyltransferase; dACC: Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; DC: Direct current; DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; EEG: Electroencephalography; EF: Electric field; E-field: Electric field; GABA: Gamma-aminobutyric acid; Glx: Glutamate and glutamine levels; HC: Healthy control; HCP: Human connectome project; ICD: International Classification of Diseases; IFG: Inferior frontal gyrus; LBP: Lower back pain; LTA: Lateral temporoparietal area; mA: Milliampere; MDD: Major depressive disorder; MNI: Montreal neuroimaging initiative; mTBI: Mild traumatic brain injury; MUD: Methamphetamine use disorder; n: Number; OCD: Obsessive-compulsive disorder; PMI: Primary motor cortex; PS: Perinatal stroke; PVI: Periventricular infarction; RPE: Rating of perceived exertion; SCZ: Schizophrenia; SD: Standard deviation; SimNIBS: Simulation of non-invasive brain stimulation; SMN: Sensorimotor Network; svTBI: Severe traumatic brain injury; tACS: Transcranial alternating current stimulation; TBI: Traumatic brain injuries; tDCS: Transcranial direct current stimulation; TEP: TMS-evoked potentials; TMS: Transcranial magnetic stimulation; TP: Temporoparietal; V/m: volts per meter; Ver: Version; VL: Vastus lateralis; vlPFC: Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex; vPFC: Ventral prefrontal cortex; YBOCS: Yale-brown obsessive compulsive score

Acknowledgments

None

Author’s contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that they have not used generative AI (a type of artificial intelligence technology that can produce various types of content including text, imagery, audio and synthetic data. Examples include ChatGPT, NovelAI, Jasper AI, Rytr AI, DALL-E, etc) and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process before submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.