Unraveling the crucial clues on the role of cellular dormancy and plasticity in cancer recurrence

- Department of Pathology, Medicine and Pharmacy Faculty, Phenikaa University, Vietnam. Nguyen Trac Street, Ha Dong District, Hanoi, Vietnam

- Department of Pathology, Hanoi Medical University, Vietnam. 1, Ton That Tung Street, Dong Da District, Ha Noi City, Vietnam

- Department of Pathology, Hospital of Hanoi Medical University, Vietnam. 1, Ton That Tung Street, Dong Da District, Ha Noi City, Vietnam

- Pathological and Cytopathological Centre, Bach Mai Hospital. 78, Giai Phong Street, Dong Da District, Hanoi, Vietnam

Abstract

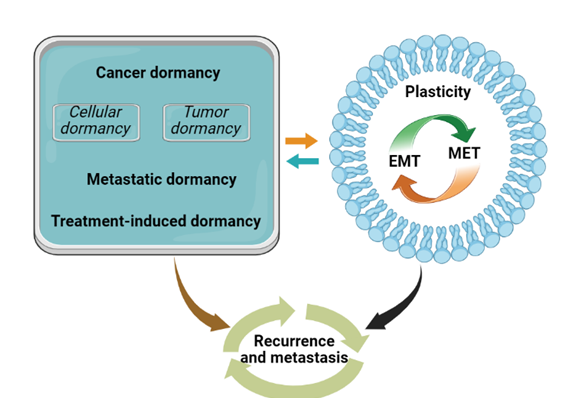

Cancer recurrence remains a major clinical challenge. Cellular dormancy and phenotypic plasticity have emerged as key contributors to this phenomenon. Dormancy is not a universal trait; it is restricted to the subset of malignant cells that acquire stem-cell-like characteristics, termed cancer stem cells (CSCs), enabling entry into a quiescent state. CSCs display both dormancy and plasticity, conferring marked therapy resistance. The crosstalk between these processes is orchestrated by an intricate framework of signaling cascades, microRNA circuits, cell-cycle regulators, and transcription-factor networks. Through this framework, tumor cells acquire stem-like features, switch phenotypes, and adopt a dormant program that permits immune evasion. Paradoxically, immune surveillance can further reinforce CSC traits, thereby promoting survival under hostile conditions, treatment resistance, and self-renewal. Sustained dormancy of residual malignant cells could therefore allow disease to be contained as minimal residual disease (MRD) rather than progressing to overt relapse. This review consolidates current insights into tumor-cell plasticity and dormancy, delineates their molecular underpinnings, and critically appraises the contentious notion of therapeutically sustaining dormancy. Emerging strategies targeting these pathways are also discussed.

Introduction

Cancer recurrence denotes the return of malignant disease after a period of clinical remission following definitive therapy.1 The interval to recurrence varies widely among patients, even among individuals with identical histologic subtype, clinical stage, and therapeutic regimen. The biological mechanisms driving recurrence are multifactorial and remain incompletely elucidated. Multiple hypotheses implicate intrinsic factors—including host anti-tumour immunity, alterations within the tumour microenvironment (TME) that either suppress or facilitate malignant proliferation, and the mutational evolution of cancer cells—in the recurrent process. Recently, the paradigms of cellular dormancy and cellular plasticity have been recognized as central to recurrence biology.

Recurrence may manifest at the primary site (local recurrence), in regional lymph nodes or contiguous tissues (regional recurrence), or at distant organs (distant recurrence).1 To harmonize terminology, an international workshop convened in Toronto, Canada, in February 2018 defined early recurrence as disease returning within five years of diagnosis and late recurrence as recurrence developing more than five years after diagnosis.2

Cellular dormancy and plasticity have therefore attracted considerable investigative attention. Accumulating evidence supports their pivotal contribution to recurrence. Tumour-cell dormancy is a dynamic state in which malignant cells enter temporary growth arrest or quiescence3 (the terms dormancy and quiescence are used interchangeably in this review). Because these cells are non-proliferative, they can withstand hostile conditions, evade immune surveillance, and resist conventional cytotoxic therapies.4 Dormant cells may persist for prolonged periods and can subsequently be reactivated by diverse stimuli.5,6 Nevertheless, the precise role of dormancy in recurrence and metastasis remains contentious.7,8,9 Whether long-term maintenance of dormancy confers clinical benefit is addressed in the following section. Dormancy is induced by both intrinsic factors, such as oncogenic mutations, and extrinsic cues, such as signals derived from the TME.10,11

Cellular plasticity denotes the capacity of cancer cells to alter their phenotype in response to environmental stimuli, thereby promoting therapeutic resistance, adaptation to heterogeneous niches, and metastatic dissemination.12,13,14 Plasticity is orchestrated by genetic and epigenetic reprogramming that enables transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states—epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and its reverse, mesenchymal–epithelial transition (MET).15 Micro-RNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as critical regulators of both dormancy and plasticity; by modulating target mRNAs, these small non-coding RNAs can maintain quiescence or, conversely, trigger re-activation of dormant cells, ultimately facilitating recurrence and metastasis.16

This review consolidates current insights into tumour-cell plasticity and dormancy, delineates the molecular pathways governing these phenomena, evaluates the controversy surrounding therapeutic induction or maintenance of dormancy, and highlights novel treatment strategies under investigation.

Dormancy and plasticity in cancer

Definitions of dormancy and plasticity

Cancer dormancy

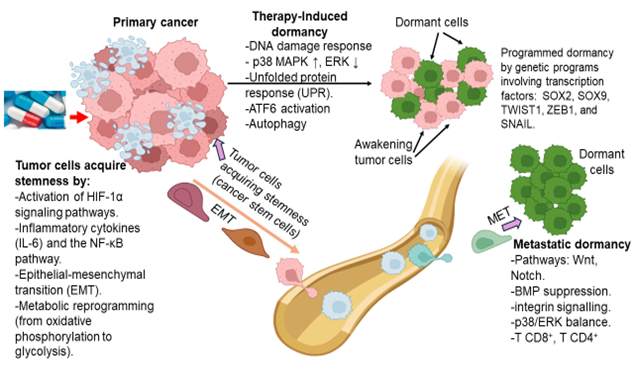

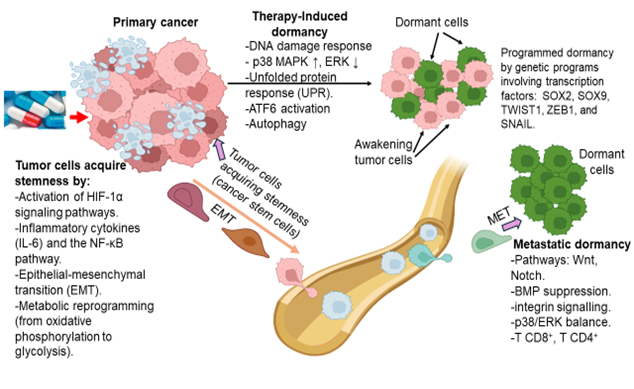

Cancer cell dormancy is an evolutionarily conserved survival strategy that enables malignant cells to endure adverse conditions by entering a hypometabolic state. Key features of dormant cancer cells include cell-cycle arrest (typically in the G0/G1 phase), chromatin condensation, and dysregulated signalling pathways. Two inter-related dormant states have been described: cellular and tumour dormancy. Cellular dormancy ( single-cell dormancy) usually occurs in disseminated tumour cells that have metastasised to distant organs; these cells can be reactivated by microenvironmental cues.17 Tumour dormancy denotes a dynamic equilibrium between cellular proliferation and death within the entire tumour mass, so that tumour volume remains stable for prolonged periods, generally owing to limited angiogenesis or immune-mediated growth suppression (Figure 1). The tumour can resume growth once environmental conditions become favourable.18 Programmed dormancy is governed by defined genetic programmes involving transcription factors such as SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2) and SRY-box transcription factor 9 (SOX9), and is frequently associated with the acquisition of stem-cell-like traits by tumour cells.19

Summary of the interaction between cellular dormancy in cancer recurrence and metastasis. Through the two properties of dormancy and plasticity, cancer stem cells are able to survive in toxic environments and evade the immune system's cytotoxic T cells, leading to cancer recurrence and metastasis. (

Metastatic and treatment-induced dormancy

Both metastatic and treatment-induced dormancy are emerging concepts that are receiving considerable research attention. Metastatic dormancy refers to the quiescent state adopted by disseminated tumour cells during the early phases of colonisation of a distant, pre-metastatic niche. During this phase, the cells remain dormant to evade immune surveillance, and their survival as well as subsequent re-awakening critically depend on the local tumour microenvironment (TME).20 Treatment-induced dormancy describes a reversible quiescent state entered by cancer cells upon exposure to cytotoxic therapies (Figure 1). During this period, cellular metabolism is minimised to support survival, and proliferation can resume once favourable conditions return.21 (

Differences between metastatic dormancy and therapy induced dormancy

| Feature | Metastatic Dormancy | Therapy-Induced Dormancy |

|---|---|---|

| Trigger | Microenvironmental cues at distant metastatic sites. | Cellular stress from chemotherapy, radiation, or targeted therapy. |

| Cell Type | Disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) in secondary organs. | Residual tumor cells surviving treatment. |

| Location | Bone marrow, lungs, liver, brain niches. | Primary tumor site or micrometastatic lesions |

| Mechanism | ECM signals (e.g. thrombospondin-1), immune surveillance, angiogenic suppression. | DNA damage response, p38 MAPK activation, unfolded protein response (UPR). |

| Pathway Involvement | Wnt, Notch, BMP suppression, integrin signaling, p38/ERK balance. | p38 MAPK↑, ERK↓, |

| Phenotype | Quiescent (G0/G1 arrest), immune-evasive, slow-cycling. | Drug-tolerant persister cells, senescent-like, metabolically active but non-dividing. |

| Escape Triggers | ECM remodeling, angiogenesis, immune suppression. | Loss of p53/p16, metabolic reprogramming, SASP signaling, therapy cessation. |

| Clinical Implication | Late relapse (years/decades post-treatment), often undetectable until reactivation. | Resistance to therapy, early relapse, minimal residual disease (MRD). |

Cellular plasticity

Cancer cell plasticity is the capacity of malignant cells to alter their phenotype in response to microenvironmental changes, thereby facilitating adaptation and evolution under selective pressures such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy. This adaptive process is driven by Darwinian selection, whereby cells with advantageous traits persist and expand, ultimately contributing to tumour recurrence and metastasis.36 Specifically, plasticity encompasses (i) reversible transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states (EMT and MET, respectively) and (ii) the acquisition or loss of stem-cell properties. EMT endows tumour cells with stemness, enabling them to remain dormant within pre-metastatic niches.15 The ability of tumour cells to modulate phenotype in response to environmental cues is therefore critical for tumour survival and progression.17 Stem-cell-like characteristics are confined to cancer stem cells (CSCs), a sub-population capable of self-renewal and multilineage differentiation.37 Plasticity allows dynamic inter-conversion between CSC and non-CSC states and represents one of the principal drivers of intratumoural heterogeneity, migration, invasion, and therapy resistance.15,17,38 (Figure 2).

Summary of the process of dormancy, and of cancer recurrence and metastasis. In the primary site, some cancer cells survive treatment by acquiring stemness and going into dormancy - also known as cancer stem cells. These cells can reactivate when conditions are favorable - called cancer recurrence. They can also leave the original site through EMT and borrow blood vessels to reach a more distant location - called the pre-metastatic niche. In the early stages, tumor cells are in a dormant state to resist toxic stress and evade the immune system. (

Basic mechanism

Dormancy mechanisms in cancer cells

To enter a dormant or quiescent state, cancer cells must be induced to arrest in the G0 phase of the cell cycle. Only a subset of cells at the primary tumor site can do so—namely those that have acquired stem-cell-like characteristics, referred to as cancer stem cells (CSCs). The underlying regulatory network is complex and is being progressively elucidated. Several classes of factors have been implicated. First, cell-cycle regulators such as the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors CDKN1B (p27^Kip1) and CDKN1A (p21), together with the tumor suppressor TP53 (p53), can promote dormancy. While p53 arrests the cell cycle in response to cellular stress and DNA damage, p27 and p21 inhibit cyclin-dependent kinases, thereby blocking proliferation and enforcing cell-cycle arrest.31,39,40 Second, a high p38/ERK low activity ratio favors dormancy; experimental cancer models demonstrate that elevated p38 and suppressed ERK signaling support a dormant phenotype.31,41 Third, adverse elements within the tumor microenvironment (TME)—including hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, and the absence of matrix-binding integrins in the pre-metastatic niche—constitute prerequisites for tumor-cell dormancy.31,42 The pre-metastatic niche is a specialized microenvironment in a distant organ where circulating tumor cells (CTCs) can lodge, survive immune attack, and ultimately initiate secondary tumors.43 Fourth, immune-mediated cues such as interferon-γ (IFNG/IFN-γ) acting through the IDO1–kynurenine–aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR)–p27^Kip1 axis, together with T cells, macrophages, and cytokines present in the TME, can promote dormancy.44 Finally, sustained shortages of nutrients and oxygen further limit tumor-cell growth and enforce dormancy.45

Mechanisms driving plasticity

Tumor-cell plasticity arises from the convergence of several molecular processes. First, epigenetic modifications, by regulating messenger RNA expression, alter gene output and protein function, thereby generating phenotypic diversity.46 Second, dysregulation of signaling cascades—including MAPK, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), Wnt, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathways—enables tumor cells to shift phenotype in response to the TME, promoting metastasis and recurrence.14,47,48 Third, microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) modulate chromatin remodeling, mRNA stability, and transcription, thereby governing stemness and phenotypic heterogeneity.46 Lastly, altered DNA methylation of genes such as PPARG coactivator-1α (PPARGC1A/PGC1α) and death-associated protein kinase-3 (DAPK3), which orchestrate metabolic pathways, equips tumor cells with enhanced resistance to stress.49,50,51 (

Summary of some differences in cellular dormancy and plasticity in cancer

| Feature | Cellular Dormancy | Cellular plasticity |

|---|---|---|

| Cell State | Quiescent (non-dividing) | Dynamic (switching between phenotypes) |

| Proliferation | Suppressed | Variable (can increase or decrease) |

| Therapy Resistance | High (due to low proliferation) | High (due to adaptive phenotype switching) |

| Reversibility | Reversible (can re-enter cell cycle) | Reversible (can shift between states) |

| Key Pathways | p38 MAPK, PI3K-Akt suppression, Notch | Wnt, Notch, EMT, stemness-related pathways |

| Role in Metastasis | Enables long-term survival pre-relapse | Facilitates invasion, metastasis, resistance |

| Stemness Association | Often overlaps with cancer stem cells | Strongly linked to stem-like traits |

| Environmental Influence | Strongly influenced by microenvironment | Highly responsive to external cues |

Molecular crosstalk of dormancy and plasticity

Cellular plasticity is a critical determinant of tumour dissemination and distant metastasis. It enables cancer cells within the pre-metastatic niche to evade immune surveillance by undergoing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)7,52,53. Through this phenotypic switch, tumour cells detach more readily from the primary lesion, facilitating dissemination to secondary sites.54,55

A subsequent mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) allows disseminated cells to exit dormancy, resume proliferation, and colonise distant organs.56,57 Thus, phenotypic plasticity endows cancer cells with the adaptability required for survival, growth, and dissemination. In an evolutionary context, cellular plasticity drives both phenotypic diversification and dormancy.57 These processes recapitulate Darwinian natural selection, whereby only cells capable of phenotypic switching and dormancy survive unfavourable conditions and expand when the environment becomes permissive.58

Alternative evolutionary models—including clonal, neutral, punctuated and barrier theories—have also been proposed. These models consider stochastic mutations, non-genetic influences, and tumour–microenvironment interactions in tumour progression.59 A detailed discussion of these theories is beyond the scope of this review.

To withstand hostile cues such as immune attack or chemotherapy, tumour cells may enter dormancy. This state is orchestrated by the transcription factors TWIST1, ZEB1 and SNAI1/SNAIL, which induce EMT via p38-MAPK activation and ERK suppression, culminating in G0/G1 arrest and repression of the cell-cycle regulators NR2F1 and SOX9.39,60,61 Dormant cells simultaneously acquire stem-like traits, characterised by expression of POU5F1/OCT4, NANOG and SOX2, thereby preserving phenotypic flexibility.40,62 (

Summary of some molecular interactions in dormancy and plasticity

| Functional Group | Molecules/Pathways | Interaction Type | Effect on Dormancy/Plasticity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Triggers | Host immune system, Chemotherapy | Activate stress signaling | Initiates dormancy via p38 MAPK activation and ERK suppression |

| Stress Signaling Pathways | p38 MAPK↑, ERK↓ | Antagonistic signaling balance | p38 promotes dormancy; ERK promotes proliferation |

| EMT Transcription Factors | Cooperative activation during EMT | Induce mesenchymal phenotype and stemness traits | |

| Cell Cycle Regulators | Downregulated by EMT TFs and stress signaling | Enforce G0/G1 arrest and suppress proliferation | |

| Stemness Genes | Upregulated by EMT and epigenetic changes | Maintain survival and plasticity during dormancy | |

| Epigenetic Modifiers | Synergistic repression of proliferation genes | Stabilize dormancy by silencing growth-promoting genes | |

| Phenotypic Plasticity | EMT ↔ MET | Reversible transitions driven by TFs and signaling shifts | EMT induces dormancy; MET enables escape and recurrence |

| Recurrence Pathways | MET, ERK↑ | Reactivation of epithelial traits and proliferation signaling | Promote exit from dormancy and tumor expansion |

The regulatory networks of cellular dormancy and plasticity in cancer recurrence

The regulatory networks that govern cancer cell dormancy and plasticity comprise multiple, complex, and interacting molecular mechanisms that can act in opposition to each other, such as maintaining cancer cell dormancy while reactivating their proliferative capacity. These networks involve cell cycle regulators, transcription factors, signaling pathways, and miRNAs.

Cell cycle regulatory networks

Cell-cycle arrest in the G0 phase constitutes a hallmark of cellular dormancy. Multiple intricate signaling cascades modulate this state. For instance, the p38 MAPK pathway suppresses cell-cycle progression by down-regulating cyclins and up-regulating CDK inhibitors, thereby enforcing dormancy31,66. The transforming-growth-factor-β (TGF-β) pathway, acting in concert with p53, induces the CDK inhibitors cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B (CDKN2B/p15), p21, and p27Kip1, similarly promoting dormancy67,68. Activation of the Notch pathway induces target genes including HES1, HEY1, MYC, cyclin D1 (CCND1), p21, and p27Kip1, thereby maintaining cells in a quiescent state and retarding tumour growth69,70.

Transcription factor networks

Master regulatory transcription factors

Cell-cycle regulatory transcription factors such as p53 and NR2F1 are upregulated by p38-activated CDK inhibitors, driving cancer cells into dormancy. Members of the forkhead box family, such as forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) and forkhead box O2 (FOXO2), participate in multiple cellular processes, including cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis and DNA damage repair.68,71,72

EMT-related transcription factors

Zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2) maintains cellular dormancy by modulating EMT.73,74 Downregulation of basigin (BSG/EMMPRIN/CD147) increases the expression of waveform proteins, EMT-induced transcription factors and dormancy markers, thereby suppressing proliferation and angiogenesis.75 EMMPRIN is a transmembrane glycoprotein that is critical for cancer progression, cell-cycle regulation and diverse cellular processes.76 EMMPRIN is regulated by transcription factors such as hypoxia-inducible factor 1 subunit alpha (HIF1A/HIF-1α) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB). NF-κB is a major transcriptional regulator of EMMPRIN, particularly during inflammation and tumorigenesis.76 HIF-1α directly regulates EMMPRIN expression under hypoxic conditions. EMMPRIN downregulation induces G1 cell-cycle arrest through reduced CCND1 and cyclin levels.77,78

Signaling pathway networks

In addition to a network of regulatory and EMT-related transcription factors, signaling pathways constitute crucial regulators of cancer-cell dormancy and plasticity. Through these pathways, tumor cells can rapidly adapt to an ever-changing extracellular milieu, thereby maintaining their viability.

Major dormancy-inducing pathways

The coordinated activity of multiple signaling cascades—including p38 MAPK/ERK (balance), PI3K–protein kinase B (AKT) (suppression), transforming growth factor-β2 (TGFB2/TGF-β2), ERK/MAPK (suppression), Wnt, Notch, RAS/MAPK, and the unfolded protein response—forms a network in several cancers that establishes and sustains stemness, enabling certain cancer cells to enter a dormant state (

Signaling pathways inducing dormancy of cancer cells

| Pathway | Main Effectors | Molecular Cascade Summary | Clinical Impact on Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| p38 MAPK / ERK Balance. | p38 MAPK, ERK |

High p38/ERK low → dormancy/apoptosis. p38 inhibits ERK via feedback | Dormancy in head & neck cancer; ERK-driven proliferation in melanoma, breast cancer |

| PI3K-Akt Suppression. | PI3K, Akt, PTEN |

PI3K → PIP3 → Akt → downstream targets. PTEN inhibits PI3K | Promotes apoptosis; inhibits growth; used in therapy resistance strategies |

| TGF-β2 Signaling. | TGF-β2, TβRI/II, |

Canonical: Non-canonical: PI3K/Akt, MAPK, Rho/ROCK | Drives EMT, immune evasion, fibrosis; dual role in tumor suppression & progression |

| ERK/MAPK Suppression. | Ras, Raf, MEK, ERK |

MEK/ERK inhibitors ↓ERK activity. Activates compensatory survival pathways | Suppresses proliferation; resistance may involve PI3K, NF1 loss; dual inhibition in trials |

| Wnt and Notch Pathways. | β-catenin, Frizzled, NICD, CSL complex |

Wnt stabilizes β-catenin → transcription. Notch cleavage → NICD → transcription | Maintains stemness; increases EMT & therapy resistance; common in colon, breast, glioblastoma |

| RAS/MAPK pathway. | RAS, RAF, MEK, ERK | RAS→RAF→MEK→suppress ERK→ G1/G0, silencing genes (p21, p27). | Cell dormancy and reactivation of dormant cells depending on environmental signals. |

| Unfolded Protein Response. |

ER stress → Adaptive or apoptotic outcome | Enables survival in hypoxia; associated with dormancy, resistance, and metastatic potential |

Major cellular plasticity-inducing signaling pathways

Via distinct mechanisms, the Wnt/β-catenin (CTNNB1), Notch, TGF-β, PI3K–AKT–mTOR 88,89, Hedgehog (Hh), Janus kinase (JAK)–signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), and NF-κB pathways often assemble into complex, interconnected networks that, in a context-dependent manner, modulate diverse aspects of cellular plasticity—such as EMT/MET transitions, acquisition of stem-like properties, evasion of immune surveillance, and adaptation to adverse microenvironments (

Comparison of major signaling pathways influencing cell plasticity

| Pathway | Main Function | Activation Mechanism | Key Transcription Factors | Impact on Plasticity | Relevance to Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt/β-Catenin. | Cell fate & stem cell renewal | Wnt inhibits β-catenin degradation | TCF/LEF | Promotes expansion & differentiation | Cancer, regeneration |

| Notch. | Binary cell fate decisions | Ligand binding → NICD cleavage & nuclear translocation | CSL (RBP-Jκ), | Maintains quiescence & EMT regulation | Neurodegeneration, fibrosis, cancer |

| TGF-β. | EMT, immune modulation, fibrosis | Ligand binds TβR → Smad activation | Smad2/3 + Smad4 | Induces stemness & fibroblast activation | Tumor progression, fibrotic diseases |

| PI3K/AKT/TOR. | Cell survival, metabolism, growth | PIP3 activation → AKT → mTOR | FOXO, HIF-1α | Enhances proliferation, survival, metabolic adaptation | Cancer, metabolic disorders |

| Hedgehog (Hh). | Patterning, regeneration | Ligand binding → SMO activation via cilia | Gli1/2/3 | Controls stem cell proliferation & niche maintenance | Medulloblastoma, basal cell carcinoma |

| JAK/STAT3. | Cytokine signaling, inflammation | Ligand activates JAKs → STAT3 phosphorylation | STAT3 | Supports stemness, immune suppression | Cancer, chronic inflammation |

| NF-κB. | Inflammation, survival, stress response | IKK activation → IκB degradation → NF-κB nuclear entry | NF-κB (p65/p50) | Facilitates reprogramming & inflammatory microenvironment | Autoimmunity, cancer, aging |

Network of miRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, single-stranded, non-coding RNAs of approximately 20–24 nucleotides that modulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level.98 In addition to transcriptional repression, miRNAs orchestrate diverse biological programmes, including cell growth, differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis, and help to maintain tissue homeostasis. They also participate in metabolism, immune surveillance and stress responses. Aberrant miRNA expression has been linked to numerous diseases, notably cancer, where individual miRNAs may behave as oncogenes or tumour suppressors; consequently, they are considered promising therapeutic targets.99 Several miRNAs serve as key regulators of cellular dormancy and plasticity: miR-34a, the miR-let-7 family and miR-125b control stem-cell characteristics;100,101 miR-200, miR-21 and miR-10b regulate the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT);102,103,104 and miR-190, miR-223, miR-101, miR-126 and miR-26b govern cellular dormancy.105,106,107,108,109 (

MiRNA networks in the regulation of cellular plasticity and dormancy in cancer recurrence

| miRNA | Key target | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| miR-200 family. | Inhibits EMT, maintains epithelial phenotype | |

| miR-34a. | Notch1, | Inhibits stemness, promotes cell death |

| let-7 family. | Inhibition of cell self-renewal and stemness | |

| miR-21. | Promote EMT, increase survival and treatment resistance | |

| miR-190. | Induces dormancy, responds to stress | |

| miR-223. | IGF1R, FOXO3a | Regulation of immune response and dormancy |

| miR-101. | Inhibition of proliferation, associated with dormancy | |

| miR-126. | VEGF, PI3K | Inhibits angiogenesis, supports dormancy |

| miR-125b. | Promotes quiescence and inhibits stemness | |

| miR-29b. | Epigenetic regulation; promotes dormancy and apoptosis | |

| miR-155. | Increased inflammation and plasticity; associated with relapse | |

| miR-10b. | Promotes EMT, invasion and metastasis |

Key miRNAs participate in networks such as signaling pathways, transcription factor networks, cell cycle regulatory networks involved in cellular plasticity and dormancy, and cancer recurrence.

| miRNA | Main target | Related Networks | Biological function | Related Cancers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-190 | Transcription factor, stress | Induces dormancy through inhibition of proliferation and stress response | Breast, melanoma | |

| miR-223 | Cell cycle, immune signaling | Promote dormancy and immune regulation | Leukocytes, stomach | |

| miR-101 | Transcription, epigenetic silencing | Reduced pro-oncogene expression; maintained dormancy via EZH2 | prostate, lung | |

| miR-126 | VEGF, PI3K | Vascular signaling and cell survival | Inhibits angiogenesis; supports non-mitotic state | Breast, lung |

| miR-125b | Apoptosis signaling, stemness | Promotes static state; reduces stemness | Breast, leukocytes | |

| miR-29b | Epigenetics, apoptosis | Modulates DNA methylation; promotes dormancy through survival gene regulation | Leukocytes, bone marrow | |

| miR-155 | Immune signaling, plasticity | Increased inflammation, altered cell phenotype, and associated with relapse | Lymphoma, breast,leukocytes | |

| miR-10b | EMT, metastasis | Induce EMT and invasion; support awakening | Breast, glioma |

Maintenance of cellular dormancy and reactivation of dormant cells

Factors regulating cellular dormancy, encompassing both the maintenance of dormancy and the reactivation of dormant cells (

Summary of some factors related to maintaining dormancy and reactivation of dormant cells

| Factors Involved in Maintaining Cellular Dormancy | Factors Involved in Reactivating Dormant Cells |

|---|---|

|

Cell Cycle Dormant cells typically arrest in G0/G1 phase. Suppression of cyclins and CDKs helps maintain this arrest. Gene Regulation Repressors of proliferation genes (like p21, p27) are upregulated. Epigenetic silencing of growth-promoting genes reinforces dormancy. Transcription Factors Certain TFs like Signaling Pathways Downregulation of mitogenic signals (e.g., MAPK/ERK) and upregulation of stress/maintenance signals (e.g., TGF-β, p38 MAPK). Metabolic Programming Dormant cells tend to favor low metabolic activity. Shift toward oxidative phosphorylation and minimal biosynthesis to conserve energy. Microenvironmental Factors Niche-derived cues (hypoxia, ECM stiffness, cytokine levels) support dormancy. For example, a low-nutrient, immune-quiet environment can reinforce quiescence. |

Immune Awakening Immune surveillance changes (e.g., inflammation or loss of immune suppression) can trigger reactivation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines may signal dormant cells to awaken. Gene Regulation Reactivation involves switching on genes that promote growth, cell cycle progression, and survival. Epigenetic reprogramming plays a key role. Transcription Factors TFs like MYC, AP-1, and NF-κB promote re-entry into the cell cycle and are often reactivated during awakening. Signaling Pathways Reactivation often involves ERK reactivation, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and PI3K/AKT pathway upregulation. Single Cell Dynamics Heterogeneity in signaling thresholds and cell state predisposes certain cells to reawaken. Stochastic fluctuations can prime cells for escape from dormancy. Metabolic Programming Cells shift to higher metabolic activity to support growth (e.g., increased glycolysis and anabolic metabolism). |

Some researchers have suggested that keeping tumor cells in a dormant state can be beneficial because these dormant cells are growth-inhibited and do not contribute to tumor growth or metastasis. This dormancy is believed to be maintained by the immune system and by specific signals from the microenvironment,121,122 which include a stable extracellular matrix, the suppression of angiogenesis,122,123 and surveillance by cytotoxic T cells.123,124 The focus of therapeutic efforts should be on supporting the microenvironment that allows disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) to remain dormant, rather than aggressively trying to eliminate them.71,125 Clinical observations have indicated that disruptions to this microenvironment—such as inflammation, tissue remodeling, surgery, or trauma—can reactivate dormant cells.126,127 Therefore, proponents of this approach have suggested that maintaining a stable state of dormancy may be a better strategy when cell removal is not feasible, as it may help prevent recurrence and metastasis.

Other researchers hold the opposing view that dormant tumor cells pose a long-term threat due to their unpredictable reactivation, which often leads to more aggressive disease recurrence and therapeutic resistance. These dormant cells can evade chemotherapy and radiotherapy because they are non-proliferative, allowing them to survive initial therapy.124,128,129 Once reactivated, they often acquire adaptive drug resistance, evade immune surveillance, and display an increased propensity for metastasis.129,130 For example, systemic recurrences of breast cancer and melanoma that occur 5–20 years after primary therapy are thought to result from dormant cancer cells re-entering the cell cycle. This perspective underscores the necessity for therapeutic strategies that specifically target and eradicate dormant cells.131 Potential approaches include modulation of the ERK/p38 signaling balance,132 inhibition of β1-integrin/FAK pathways,133 and enhancement of immune-mediated clearance mechanisms.124

These differing opinions highlight a significant dilemma between disease prevention and eradication. Controlled reactivation of dormant cells may have both beneficial and detrimental effects, but it also offers several therapeutic opportunities. First, reactivation can sensitize chemoresistant dormant cells to conventional treatments.21,120 Second, a planned activation–elimination strategy may help prevent late recurrence by avoiding the sudden awakening of dormant cells that leads to metastasis years later.119 Third, elucidating the pathways that regulate the re-entry of dormant cells into the cell cycle could improve our understanding of cancer progression and drug resistance.21

We contend that both therapeutic strategies—sustaining dormancy and eradicating dormant tumor cells (DTCs)—offer distinct advantages and limitations contingent upon the underlying pathobiology and available surveillance modalities. Preservation of the niche to maintain dormancy may be appropriate when the tumor microenvironment is relatively stable and robust monitoring systems are in place. Conversely, when stimuli that promote reactivation—such as inflammation, surgical trauma, or remodeling of the extracellular matrix—are present, interventions designed to detect and eliminate DTCs should be prioritized. At present, evidence is insufficient to endorse either strategy as universally superior. A pragmatic strategy is to individualize therapy according to microenvironmental attributes, biomarkers predictive of dormancy or reawakening, and patient-specific risk–benefit profiles. The principal challenge lies in determining whether dormancy is sufficiently stable to be maintained or if dormant cells are poised to reactivate. Future therapeutic paradigms will likely integrate both tactics: reinforcing the microenvironment to preserve dormancy while deploying precision agents to selectively ablate residual dormant clones. Priority research objectives include the development of biomarkers capable of quantifying dormancy stability, detecting incipient awakening, and guiding clinical trials that evaluate these combinatorial strategies.

Evolutionary perspectives on cellular dormancy and plasticity

Examining the evolution of cells from unicellular to multicellular organisms is crucial to understanding the dormancy and plasticity of cancer cells. Consequently, many properties of cancer cells have been discovered that help them proliferate, metastasize, develop drug resistance, and reactivate.

Cellular dormancy: From evolutionary adaptation to cancer

Cellular dormancy represents an evolutionarily conserved survival strategy that enables cells to withstand adverse conditions by entering a state of reduced metabolic activity. This phenomenon is observed in organisms ranging from unicellular species that generate spores or cysts to complex multicellular species in which tissue-resident stem cells employ dormancy to facilitate tissue repair and preserve homeostasis.134,135 Underlying molecular mechanisms rely on sophisticated sensing systems mediated by G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and downstream signaling cascades, including PI3K–AKT and p38 MAPK, which ultimately activate gene programs required for spore or cyst formation and entry into dormancy.136 Cancer cells similarly deploy diverse surface receptors to detect environmental stressors: integrins sense alterations in the extracellular matrix,137 Toll-like receptors (TLRs) recognize danger-associated signals,138 receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) coordinate survival pathways under stress,139 and Notch receptors modulate cell-fate decisions.92 Collectively, these receptor-mediated mechanisms enable cancer cells to evade immune surveillance, acquire therapeutic resistance, and remain poised for reactivation, thereby driving disease relapse.

Cellular plasticity in evolution and adaptation to the environment

Cellular plasticity—the capacity of a cell to alter its phenotype in response to environmental cues—is critical for development, tissue repair, and disease progression.57,140 In unicellular organisms, this plasticity relies on quorum sensing and epigenetic remodeling, enabling adaptation without genetic change.141,142 In multicellular organisms, plasticity is indispensable for embryogenesis and for adaptation to environmental challenges.143 Cancer cells display pronounced plasticity, shuttling between epithelial and mesenchymal states to augment their migratory and invasive capabilities.144 This adaptability allows them to acquire stem-cell-like properties, thereby fostering tumor heterogeneity and resistance to therapy.144 Anticancer treatments impose strong selective pressures; consequently, cancer cells develop genetic or epigenetic alterations that enable them to survive through enhanced drug efflux, epigenetic reprogramming, and the activation of alternative signaling cascades, including PI3K–AKT, MAPK, and NF-κB.145

Cellular dormancy and plasticity may likewise have been pivotal for the origin and survival of early life on Earth. Only organisms capable of switching to a suitable phenotype and acquiring sufficient resistance to adverse environmental conditions could avoid extinction.134 By analogy, only tumor cells that attain stemness —cancer stem cells (CSCs)— during their lifespan can survive adverse environmental conditions and resist therapy owing to their ability to become dormant and their plasticity.7,143

Clinical manifestations of dormancy and plasticity in cancer recurrence

The dormancy and plasticity of cancer cells are pivotal determinants of the clinical course of cancer. Only those cancer cells capable of genome reprogramming toward a stem-like state under adverse conditions survive therapy. Dormant cells typically display plasticity and resistance to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immune-mediated apoptosis, thereby forming a reservoir for recurrence once conditions become favorable.146

Dormant tumour cells are continuously shaped by the tumour microenvironment (TME), which remains in intimate contact with them and modulates both dormancy and phenotypic plasticity. Consequently, the TME orchestrates cancer-cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and drug resistance. Integrin receptors within the stromal extracellular matrix (ECM) are critical in this regard,133,147 as they constitute the first point of contact for disseminating cancer cells, permitting adhesion to the pre-metastatic niche.148 Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) define ECM composition and promote tumour progression by regulating integrins and signalling pathways such as TGF-β.149 Nevertheless, the precise mechanisms by which the ECM governs cancer-cell dormancy remain to be elucidated.

The ECM also confers therapy resistance by functioning as a mechanical barrier and by engaging integrin-dependent signalling that sustains cancer stem-cell (CSC) pools.150 Within the tumour stroma, immune cells contribute to immune-mediated dormancy: CD8⁺ and CD4⁺ T cells secrete interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), which arrest tumour cells in G0/G1, thereby suppressing proliferation and preserving dormancy.124,151 Immune-checkpoint pathways further modulate this balance; engagement of programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1/PDCD1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4 (CTLA-4) can maintain dormancy or prevent reactivation. Dormancy is additionally reinforced by CD4⁺ T-cell-derived chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10, whose anti-angiogenic properties restrict tumour activity and promote quiescence.152

Within minimal residual disease (MRD) niches, dormant cells may escape immune surveillance by up-regulating the checkpoint ligand PD-L1 (CD274/B7-H1), thereby suppressing cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) activity. Resistance to apoptosis is further mediated by epigenetic silencing of suppressor of cytokine signalling-1 (SOCS1) in concert with cytokine signalling.153 Natural killer (NK) cells likewise exert direct cytotoxicity and shape T-cell responses, whereas CD8⁺ T cells help preserve equilibrium with dormant tumour cells.153

Clinical investigations are increasingly clarifying the roles of dormancy, plasticity, immune effectors, and signalling pathways in recurrence and therapy resistance (

Crucial original research related to many aspects of tumor cell dormancy and plasticity in clinical and preclinical settings.

| Dormancy & Plasticity | Preclinical/clinical model | Sample/ experimental | Key findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signalling-driven dormancy — ERK/p38 ratio controls proliferation vs dormancy | Human carcinoma cell lines + mouse xenografts (mechanistic in vivo model) | Multiple human lines and several mouse cohorts/ xenograft experiments (see paper for per-experiment n). | High p38 : ERK activity (low ERK) drives long-term growth arrest (dormancy) in vivo; manipulating uPAR/integrin/ERK–p38 converts dormancy ↔ outgrowth. Mechanistic foundation for microenvironmental control of dormancy. | Aguirre-Ghiso JA |

| Transcriptional/epigenetic dormancy node (plasticity to quiescence) — NR2F1-driven program | Preclinical mouse DTC models + analyses of human DTC samples (translational) | Multiple in vivo DTC experiments + human DTC cohorts/validation samples (see methods). | NR2F1 activates SOX9 / RARβ / CDK inhibitors and global chromatin repression to induce quiescence in disseminated tumour cells (DTCs); blocking NR2F1 reactivates DTC outgrowth. | Sosa MS et al. |

| Pharmacologic induction of dormancy — NR2F1 agonist shows dormancy induction across models | Preclinical: 3D cultures, patient-derived organoids, PDXs, and mouse metastasis models | Multiple in vitro and in vivo experiments across cell lines, organoids, and PDXs (replicates described in paper). | An NR2F1-specific small-molecule agonist induced transcriptional dormancy programs, arrested growth of cancer cells, and reduced metastatic outgrowth in vivo — proof of concept that dormancy can be therapeutically induced. | Khalil BD et al. |

| ECM-driven dormancy & reactivation (plasticity via matrix remodeling) — fibronectin matrix maintenance and MMP-mediated awakening | Long-term in vitro dormancy assays on defined ECM / 3D matrices (breast cancer lines) | Screened ~23 human breast cancer cell lines; subsets sustained dormancy for weeks in culture (detailed line counts/timepoints in paper). | Cells that enter long dormancy build a fibrillar fibronectin matrix (α5β1/αvβ3, ROCK, TGFβ2); outgrowth after dormancy required MMP-2–mediated fibronectin degradation — ECM assembly/disassembly controls dormancy ↔ reactivation. | Barney LE et al. |

| Organ-specific microphysiologic niche induces dormancy — liver MPS shows spontaneous quiescence | All-human liver microphysiologic system (primary hepatocytes + NPCs) seeded with breast cancer cells (ex vivo organoid-like MPS) | Experiments with MDA-MB-231 (and other lines) using donor primary hepatocytes; system maintains hepatic function over ~2 weeks (multiple donors/replicates). | A subset of breast cancer cells became viable but non-proliferative (spontaneous dormancy) within the human liver microphysiologic system — demonstrates organ niche alone can impose dormancy. | Clark AM et al. |

| Engineered bone-marrow microenvironment (eBM) — bone niche remodeling and colonization | Tissue-engineered human bone-marrow construct colonized by breast cancer cell lines and patient organoids | Multi-condition experiments; validated with primary patient-derived breast cancer organoids and TNBC lines (replicates reported). | An engineered human bone-marrow model supports colonization and reveals how breast cancer cells remodel hematopoietic niche cues that influence proliferation vs quiescence — humanized platform to interrogate dormancy. | Baldassarri I et al. |

| Bone-on-a-chip (microfluidic) — niche heterogeneity controlling dormancy | 3D-printed bone-on-a-chip with GelMA hydrogels, MSCs, osteoclast precursors and tumour cells | Device experiments with cancer cell lines (A549 example), MSCs and osteoclast lineage cells; multiple technical/biological replicates. | The platform recapitulates discrete bone niches (dormancy vs perivascular vs “vicious cycle”) and allows study of niche-dependent reactivation, invadopodia formation and tumor–bone interactions under flow. | Ji X et al. |

| Cell–cell 3D interactions drive dormancy (cannibalism & plasticity) — hanging-drop cocultures of MSCs + cancer cells | 3D hanging-drop spheroid cocultures with MDA-MB-231 BCCs and bone marrow MSCs; multiple culture replicates; confirmatory in vivo experiments in paper | Authors show in vitro cannibalism phenomena across replicates; in vivo corroboration reported. | In hanging-drop 3D cocultures, breast cancer cells cannibalize MSCs under stress, which correlates with a dormancy-like, more resilient phenotype and suppressed immediate tumor formation — highlights how direct cell–cell interactions in 3D influence dormancy/plasticity. | Bartosh TJ et al. |

| EMT/partial-EMT plasticity states — high-resolution single-cell evidence | Genetic mouse tumour models (SCC) and single-cell profiling; translational profiling across tumours | Extensive single-cell datasets from mouse models and patient samples (hundreds–thousands of cells across tumors). | Identified discrete intermediate (hybrid) EMT states in vivo with distinct invasiveness, stemness and plasticity properties — supports a model where plasticity (not binary EMT) enables survival, dissemination and therapy resistance relevant to recurrence. | Pastushenko I et al. |

| Single-cell EMT/MET trajectories in human tumours — mapping plasticity in clinical samples | Patient tumour specimens + mass-cytometry and single-cell analyses (translational) | Single-cell / mass-cytometry datasets across patient samples and time-course experiments (detailed counts in paper). | Constructed an EMT–MET phenotypic map (PHENOSTAMP) showing multiple EMT/MET states in human lung tumours and trajectories between them — clinically relevant single-cell evidence of plasticity that can underpin dormancy/reactivation dynamics. | Karacosta LG et al. |

| Adaptive immunity enforces an ‘equilibrium’ (immune-mediated dormancy) — immune system restrains occult tumours (immune equilibrium). | Chemical carcinogenesis mouse model comparing immunocompetent vs immunodeficient hosts (in vivo). | Wild-type mice were tumorigenic with the chemical carcinogen 39-methylcholanthrene, treated with immunoglobulin, and monitored for tumor progression. | Demonstrated an immune-mediated equilibrium phase in which adaptive immunity (T cells/IFNγ) holds transformed cells in check (occult, poorly proliferative neoplastic cells) — distinct from elimination or escape. Foundational experimental proof that adaptive immunity can maintain long-term tumour dormancy. | Koebel et al. |

| Cytostatic CD8⁺ T cells restrain disseminated cells (tissue-specific dormancy control) — CD8 T cells slow/hold DTCs. | Spontaneous murine melanoma model; depletion/functional studies of CD8 T cells (in vivo). | Mouse cohorts, depletion experiments; ATCC TIB-210 rat and depleted CD8+T cells | Showed disseminated tumour cells appear early and that cytostatic CD8⁺ T cells contribute to tissue-specific dormancy (CD8 depletion accelerated metastatic outgrowth). Supports role of cytostatic T cells in maintaining dormancy. | Eyles et al. |

| NETs (neutrophil extracellular traps) awaken dormant cells — inflammation → proteolytic ECM remodelling → reactivation | Mouse lung inflammation / experimental metastasis models (tumour cell lines D2.0R, MCF7; LPS or smoke models to trigger NETs). | Multiple mouse experiments/ conditions; murine D2.0R cell line, human MCF-7 cell line, Isolated neutrophils were cultured | Sustained inflammation caused neutrophil-NET formation; NET-associated proteases (NE, MMP9) cleaved laminin → remodeled ECM that activated integrin α3β1 on DTCs and triggered exit from dormancy. NET blockade or DNase prevented awakening. Strong mechanistic link: inflammation/NETs awaken dormant DTCs. | Albrengues et al. |

| A defined CD8⁺ T-cell subset (CD39⁺PD-1⁺) enforces metastatic dormancy — T-cell–mediated dormancy with translational correlation. | Preclinical murine breast cancer dormancy models + high-dimensional single-cell mapping; translational correlation with human breast cancer samples (IHC / multiplex IF and survival analysis). | Preclinical single-cell and functional studies; human cohort n = 54 for disease-free survival correlation. | Identified CD39⁺PD-1⁺CD8⁺ T cells in tumors and dormant metastases; blocking TNFα/IFNγ disrupted dormancy in mice. In human samples, high intra-tumoral density of this subset correlated with longer disease-free survival — supports specific T-cell subsets as dormancy enforcers. | Tallón de Lara et al. |

Treatment strategies based on the mechanism of tumor cell dormancy and plasticity

Targeting cancer-cell dormancy and its associated plasticity represents an increasingly important avenue in oncology. Owing to their stem-like properties, dormant tumour cells display marked plasticity, resist conventional therapy, and are capable of self-renewal after re-awakening, ultimately driving disease relapse. Current therapeutic concepts include:

-

Inhibition of pro-survival signalling. Quiescent cells depend on pathways such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR and ERK/MAPK for survival under stress. Agents such as selumetinib, a MEK inhibitor, can suppress their reactivation.

166 -

Prevention of re-entry into the cell cycle. Dormant-cell awakening can be curtailed by neutralising cytokines (e.g., interleukin-6 and colony-stimulating factor-3) and by disrupting extracellular-matrix–integrin interactions that trigger proliferative signalling.

166 -

Exploitation of cellular plasticity. Because plasticity underlies drug resistance and metastatic competence, strategies that either lock cells in a non-proliferative state or force terminal differentiation may limit relapse. Combination regimens that simultaneously target proliferating and dormant populations are showing promise.

167 -

Immunotherapeutic eradication. Dormant cells can evade immune surveillance; therefore, immune-checkpoint blockade and other immunomodulators are being investigated to facilitate their clearance.

166 ,168 -

Biomarker development. Mechanistic insights into dormancy are enabling identification of biomarkers that forecast recurrence risk and therapeutic response.

120 ,166 Elevated circulating levels of specific microRNAs—miR-21 (promotes proliferation and metastasis), miR-200c (regulates epithelial–mesenchymal transition) and miR-23b (linked to dormancy)—have been correlated with breast-cancer relapse.169

Key challenges and future research directions

Cancer cells behave as independent, autonomous entities that evade physiological control, surpassing even the most sophisticated mechanisms of the human immune system. They can inactivate the PD-1 immune checkpoint on cytotoxic T lymphocytes by endogenously expressing its ligand, PD-L1. Notably, the efficacy of virtually every novel therapeutic regimen declines soon after implementation as treatment-resistant cancer cell clones emerge. A further challenge is the capacity of malignant cells to acquire stem-like characteristics, entering a quiescent state that permits immune evasion and therapeutic resistance, yet preserves plasticity enabling proliferation and phenotypic switching upon reactivation. Consequently, identifying strategies to eradicate tumor cell dormancy and plasticity remains one of the most formidable objectives in oncology. Although substantial progress has been achieved, considerable obstacles persist.

Key challenges

-

The lack of reliable biomarkers: Because dormant tumor cells cannot be visualized by conventional methodologies such as histopathology or standard imaging modalities, the identification and validation of robust, specific biomarkers are critical.

120 ,166 -

Drug resistance: Dormant tumor cells are arrested in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle, and their basal metabolism is markedly reduced, allowing them to evade therapies that target proliferating cells. Their phenotypic plasticity enables rapid switching, contributing to drug tolerance and relapse.

144 -

Limitations of current in vitro and in vivo models: Existing models fail to recapitulate the dormant state of tumor cells and do not accurately reproduce the tumor microenvironment (TME) or pre-metastatic niches.

120 ,168 Consequently, therapeutic testing in these systems may yield misleading results. -

Gap in clinical translation (“the valley of death”): Although promising preclinical data have been generated for a limited number of dormancy-targeted therapies, comparable benefits have not yet been demonstrated in the clinic. Integrating such strategies into standard-of-care regimens therefore remains a substantive challenge.

120

Future research directions

Cellular dormancy and cellular plasticity are recognized as pivotal drivers of cancer recurrence, yet they remain incompletely understood. Therefore, future investigations should prioritize refined methodologies that accurately identify dormant cells and either prevent their re-activation or the initiation of dormancy.

-

State-of-the-art single-cell and spatial transcriptomics: Single-cell transcriptomics enables interrogation of gene-expression profiles in individual cells, facilitating the detection of cells with dormancy-associated signatures that may be missed by conventional bulk analyses. Spatial transcriptomics simultaneously maps these signatures in situ, permitting evaluation of micro-environmental cues that sustain dormancy or trigger re-awakening, and allows longitudinal tracking of phenotypic evolution that underlies drug resistance and recurrence.

170 -

Artificial-intelligence–driven predictive modelling: Advances in AI are ushering in a new era of understanding and managing cancer recurrence, particularly through the identification of dormant cells and characterization of cellular plasticity. With multidimensional data-integration capacity, the Clinical Histopathology Imaging Evaluation Foundation (CHIEF) model can infer tumour molecular attributes from histological images, aiding in the recognition of dormant cells that pose a risk of relapse.

171 AI-based platforms can also synthesise genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic and epigenomic data, enabling comprehensive appraisal of tumour biology, refined recurrence prediction and subsequent personalisation of therapeutic regimens and follow-up.172 -

Targeting epigenetic and metabolic vulnerabilities: Epigenetic analyses can reveal chromatin states that permit tumour cells to persist in dormancy, and pharmacological modulation of these states can suppress EMT by regulating pertinent genes.

173 Metabolic profiling can distinguish dormant cells by their low-flux signatures—such as reliance on oxidative phosphorylation and fatty-acid oxidation—thereby differentiating them from proliferative counterparts. Because metabolic and epigenetic programmes interact to dictate cancer-cell state, co-targeting both processes may enhance therapeutic efficacy and diminish recurrence risk.174 -

Modulating the tumour micro-environment (TME): Dormancy is maintained by TME factors including hypoxia, cytokine milieu and extracellular-matrix stiffness, which also foster immune evasion and drug resistance.

175 Strategies that re-engineer the TME—e.g., adjusting pH, oxygenation or extracellular-matrix composition—to improve drug penetration, invigorate antitumour immunity and curtail dormant-cell survival are therefore under active investigation.176

Conclusions

Cancer recurrence remains a major clinical challenge, largely driven by two interrelated phenomena: cellular dormancy and cellular plasticity. These mechanisms enable subsets of cancer stem cells (CSCs) to withstand therapy and subsequently re-enter the cell cycle. Through phenotypic plasticity, malignant cells can disseminate from the primary tumour to distant organs, including pre-metastatic niches. During the initial phase of niche colonisation, disseminated tumour cells frequently enter a dormant state that permits survival under cytotoxic stress and evasion of immune surveillance. A complex signalling network—including miRNAs, cell-cycle regulators, and transcription factors—orchestrates the crosstalk between dormancy and plasticity. Paradoxically, prolonging dormancy, rather than triggering reactivation, may be clinically beneficial, as the disease then persists only as minimal residual disease (MRD). Consequently, it is imperative to predict and prevent recurrence by identifying dormant tumour cells and developing interventions that either eradicate them or maintain their quiescence. Future research should prioritise the use of advanced biological technologies to devise strategies that actively modulate dormancy and plasticity in cancer cells.

Abbreviations

Akt: Ak strain transforming; AP1: activator protein 1; ATF4: Activating Transcription Factor 4; ATF6: Activating Transcription Factor 6; BAK1: BRI1- Associated Receptor Kinase 1; BAG: Basigin (another name of EMMPRIN); BMP: Bone Morphogenetic Protein; CAFs: Cancer-associated fibroblasts; CD147: cluster of differentiation 147 (another name of EMMPRIN); CDK: Cyclin-Dependent Kinase; CHOP: C/EBP homologous protein; CKIs: Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors; COX-2: Cyclooxygenase-2; CSCs: cancer stem cells; CSL: CBF1, Suppressor of Hairless (Su(H)), and Lag-1 protein: CBF1; CTCs: Circulating tumor cells; CTL: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte; CTLA-4: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4; CXCL9: Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9; DAPK3: Death-Associated protein kinase 3; DNMTs: DNA Methyltransferases; DTCs: Disseminated tumor cells; ECM: Extracellular matrix; eIF2α: eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α; EMMPRIN: Extracellular Matrix Metalloproteinase Inducer; EMT: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; EZH2: Enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit; FOXO1: Forkhead box O1; G-CSF: Granulocyte-Colony Stimulating Factor; Gli1: Glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1; GPCRs: G protein-coupled receptors; HDACs: histone deacetylases; HES1: Hairy and Enhancer of Split-1; HEY1: Hairy/enhancer of split related with YRPW motif 1; HIF-1α: Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 Alpha; HMGA2: High Mobility Group AT-hook 2; hNanog: Homeobox protein NANOG; HOXD10: Homeobox D10; IFN-γ: Interferon-gamma; IGF1R: Insulin-Like growth factor 1 receptor; IKK/IKB: IkappaB kinase; IL-6: Interleukin-6; IRE1: Inositol-requiring enzyme type 1; JAKs: Janus Kinase; LIN28: conserved RNA-binding protein called lin-28 homolog; lncRNAs: long non-coding RNAs; MANL: Mammalian Mastermind-like proteins; MCL1: Myeloid cell leukemia‐1; MEK: mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase; MET: Mesenchymal-epithelial transition; MiRNAs: MicroRNAs; MRD: Minimal residual disease; mRNA: Messenger RNA; MYC: Myeloid Cytomatosis; NF1: Neurofibromatosis 1 gene; NF-κB: Nuclear Factor Kappa B; NICD: Notch intracellular domain; NR2F1: Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 2 Group F Member 1; OCT4: Octamer-binding transcription factor 4; PD1: Programmed cell death protein-1; PDCD4: Programmed Cell Death 4; PD-L1: Programmed Death-Ligand 1; PERK: protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase; PGC1α: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha; PI3K: phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase; PIP3: Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate; PTEN: Phosphatase and TENsin homolog deleted on chromosome 10; RAF: Rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma; RAT: RAt Sarcoma; RBP-Jk: Recombination signal sequence-binding protein Jκ; RhoC: Ras homolog gene family, member C; ROCK: Rho-associated protein kinase; RTKs: Receptor tyrosine kinases; SASP: Senescence-Associated secretory phenotype; SHIP1: inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase 1; SMAD4: Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4; SMO: smoothened, frizzled class receptor; SNAIL: zinc-finger transcription factor family; SOCS1: Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1; SOX2: SRY-box transcription factors 2; SOX9: SRY-related HMG box gene 9; STAT3: Signal Transducer and activator of transcription 3; TCF/LEF: T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor family; TGF-β2: transforming growth factor β2; TFs: transcription factors; TLRs: Toll-like receptors; TPM1: Tropomyosin 1; TWIST1: transcription factor Twist-related protein 1; TβRI: TβRI receptor; UPR: unfolded protein response; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; XBP1: IRE1α-X-box-binding protein 1; ZEB1: Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Phenikaa University and Phenikaa University Hospital, and Hanoi Medical University where we work for supporting this study.

Author’s contributions

Nguyen Van Hung: main role on methodology, layout and content. Tran Ngoc Minh and Nguyen Tuan Thanh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Original manuscript preparation; Illustrations were created by the authors using free tools from Biorender. All authors read and edited the manuscript before submission.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

None.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of not using AI in writing the manuscript

The authors declare that they did not use AI in writing the manuscript before submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.