Evaluation of some biomarkers for prediction of graft rejection and death after 3 months postoperative living donor liver transplantation

- Gastrointestinal Surgery Center, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt

- College of Medical Technical, Al-Farahidi University, Baghdad, 10021, Iraq

- College of Dentistry, Al-Farahidi University, Baghdad, 10021, Iraq

- Biochemistry Department, Biotechnology Research Institute, National Research Centre, Giza, Egypt

Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to identify serum biomarkers measured during the early postoperative period following living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT) that can predict graft rejection (GR) and patient survival (PS).

Methods: Postoperative GR and PS were evaluated in 120 LDLT recipients. Serum concentrations of candidate biomarkers obtained on postoperative days (POD) 1–4 were correlated with subsequent outcomes. Receiver-operating-characteristic analysis was used to determine cutoff values predictive of GR and PS.

Results: Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TB), direct bilirubin (DB), γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and the international normalized ratio (INR) measured on POD1–POD4 were independently associated with GR at 3 months. For PS, the most informative variables across the same period were alanine aminotransferase (ALT), AST, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), INR, C-reactive protein (CRP), uric acid (UA), and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR).

Conclusions: The identified biomarkers represent rapid, inexpensive, and reliable early predictors of postoperative risk for GR and PS in LDLT recipients.

Introduction

Liver transplantation (LT) is the definitive treatment for irreversible acute and chronic liver diseases 1. Graft rejection (GR) remains a major obstacle to graft survival and overall patient mortality in liver transplant recipients (LTRs) 2. In LTRs, GR is traditionally diagnosed by invasive liver biopsy 3. Current post-transplant survival rates are 89.6 % and 91.8 % at 1 year, 80.8 % and 83.8 % at 3 years, and 72.8 % and 76.1 % at 5 years for grafts and patients, respectively 4.

Compared with the standard method of care, namely liver biopsy, biomarkers provide a safer and contemporary means to identify and detect transplant rejection 5,6. These biomarkers offer a novel strategy for early risk stratification of GR 7. Biomarkers and molecular mechanisms of injury have been investigated in numerous studies to predict GR; however, there is still no global consensus on the early detection of graft rejection in clinical practice 8,9. A readily available biomarker capable of predicting short-term outcomes early in the postoperative course could permit prompt intervention and thereby decrease morbidity and mortality 10. Therefore, early non-invasive diagnosis of rejection may enable proactive management and improved outcomes 8. Nevertheless, no investigation has developed a clinically applicable protocol that would enable routinely accessible post-transplant serum analytes to be employed for graft rejection and patient survival prediction 11,12.

Through the analysis of routine postoperative clinical tests from postoperative day (POD) 1 to POD 4 in patients undergoing living-donor LT, this study aims to identify clinically practicable serum biomarkers that can discriminate patients at high risk of graft rejection and mortality within three months of LT. Furthermore, receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to assess the diagnostic accuracy and cut-off values of these clinical parameters as non-invasive markers, underscoring their potential utility as indicators of post-transplant graft rejection and patient survival.

Methods

Patients

This retrospective study was conducted in 120 adult recipients who underwent living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) at the Gastrointestinal Surgery Center, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University. The attending physician collected clinical samples from the patients. All living donors and recipients provided written informed consent prior to enrolment, and written consent was also obtained from the attending physician. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Damietta Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University (Egypt) (DFM-IRB 00012367-25-04-007). As this was a retrospective analysis, the study was not registered as a clinical trial. Patients with advanced chronic liver disease or acute fulminant liver failure refractory to medical or surgical treatment were included. Under these conditions, life expectancy is markedly reduced because of end-stage liver disease. Potential living donors aged 18–60 years were required to have ABO-compatible blood type and suitable hepatic anatomy. Donors with significant comorbidities, including malignancy, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, or intrinsic liver disease, were excluded. The eligibility criteria for transplantation complied with the practice recommendations of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) 13. All recipients were managed according to the standardized postoperative care protocol of the Gastrointestinal Surgery Center, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University. No surveillance liver biopsies were performed during postoperative days (POD) 1–4; biopsy was undertaken only when graft rejection was suspected. A uniform induction immunosuppressive protocol was administered to all recipients.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they exhibited any of the following conditions: pregnancy; women of childbearing potential without effective contraception; end-stage cardiac, pulmonary, or neurologic disease; severe or irreversible pulmonary hypertension; active, untreated infection (excluding spontaneous bacterial peritonitis); active extrahepatic malignancy (except neuroendocrine tumors); active substance abuse; requirement for combined liver and heart, lung, pancreas, bone marrow/stem-cell, or intestinal transplantation; psychiatric illness with active symptoms or behavioral patterns that could impair adherence to post-transplant therapy; immunodeficiency, including HIV-positive serology or AIDS; inadequate social support; complete portal and mesenteric venous thrombosis; moribund status with a limited life expectancy.

Graft rejection

Graft rejection in the present study—defined as acute cellular rejection—was assessed histopathologically within 90 days after liver transplantation (LT). The diagnosis and grading were established according to the Banff criteria 14. Among the 25 rejection cases, 15 were classified as mild (rejection activity index [RAI] 4–5) and 10 as moderate (RAI 6–7). Chronic or severe rejection was not observed. Overall patient survival was monitored until death or the end of the study period. Graft-related mortality excluded deaths attributable to causes other than liver failure. No patients were lost to follow-up during the study period.

Biochemical analysis

On the preoperative day and on postoperative days 1–4, 5 mL of peripheral blood was collected from each patient. Each sample was divided into two aliquots: one aliquot was placed in a plain, sterile tube for serum separation, whereas the second aliquot was transferred to a tube containing anticoagulant for hematological evaluation. The following parameters were determined in freshly obtained specimens by routine biochemical and immunochemical methods: aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), uric acid (UA), C-reactive protein (CRP), and the complete blood count (CBC). Alpha-fetoprotein was quantified by immunofluorescence assay (IFA), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated using the Steven K. Thompson equation 15 based on the entire population of eligible cases, a pre-specified confidence interval, and an acceptable margin of error to ensure adequate statistical power. Descriptive data are presented as median (interquartile range, IQR) and were compared with the Mann–Whitney U-test. Normality was assessed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical variables are expressed as proportions and were compared with the chi-square (χ) test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. To evaluate the ability of independent variables to discriminate between the rejection and non-rejection groups and to stratify 3-month survival, receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. Optimal cut-off values were determined using the Youden index. Patient survival was estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method, and curves were compared using the log-rank test. Associations between independent variables and rejection were explored with univariate logistic regression, and the predictive value of variables at their optimal cut-offs for survival was assessed with Cox proportional hazards regression. Regression results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) or hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All tests were two-tailed, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 26.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 120 patients who underwent living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) were enrolled; 95 showed no evidence of rejection, whereas 25 developed acute rejection. The baseline characteristics of both groups and the distribution of liver disease etiologies are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Among the non-rejection cohort, 18 (18.9 %) patients were female and 77 (81.1 %) were male, and the median age was 52 years (IQR, 43–57). In the rejection cohort, 7 (28 %) patients were female and 18 (72 %) were male, with a median age of 46 years (IQR, 31–55). The principal indications for transplantation were hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related cirrhosis, documented in 45 non-rejection cases (47.4 %) and 11 rejection cases (44 %), and alcoholic cirrhosis, present in 89 non-rejection cases (93.7 %) and all 25 rejection cases (100 %). Hepatocellular carcinoma was identified in 24 patients without rejection (25.3 %) and in 2 patients with rejection (8 %). Percentages of underlying etiologies are non-exclusive because some recipients harbored multiple causes of liver disease. The frequencies of cholecystitis, cholestasis, steatosis, autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, Budd–Chiari syndrome, and portal vein thrombosis did not differ significantly between the two groups (P > 0.05).

The most significant biochemical variables distinguishing patients with and without rejection during postoperative days (POD) 1–4 at 3 months after living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT) were AST on POD4 (AST4), total bilirubin on POD1–3 (TB1–3), direct bilirubin on POD2–3 (DB2–3), γ-glutamyl transferase on POD2 (GGT2), and international normalised ratio on POD1 (INR1) (P < 0.05), whereas the most highly significant variables were TB4 and DB4 (both P < 0.0001;

Supplementary Figure S1 illustrates overall survival in 120 patients at 3 months post–living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT). Eleven patients died, corresponding to a 9.2 % mortality rate, while 109 survived (90.8 %). The mean ± SE survival time was 84.8 ± 1.65 days (95 % CI, 81.6–88.0 days). Supplementary Figure S2 compares survival between recipients with and without biopsy-proven rejection. Patients without rejection (n = 95) achieved a 93.7 % survival rate, whereas those with rejection (n = 25) exhibited an 80.0 % survival rate (log-rank χ = 4.32, P = 0.038). During the 3-month postoperative interval, 11 deaths were recorded: five were graft-related and six were attributable to non-graft-related causes. Consistent with these findings, no significant association was observed between graft rejection and mortality (Supplementary

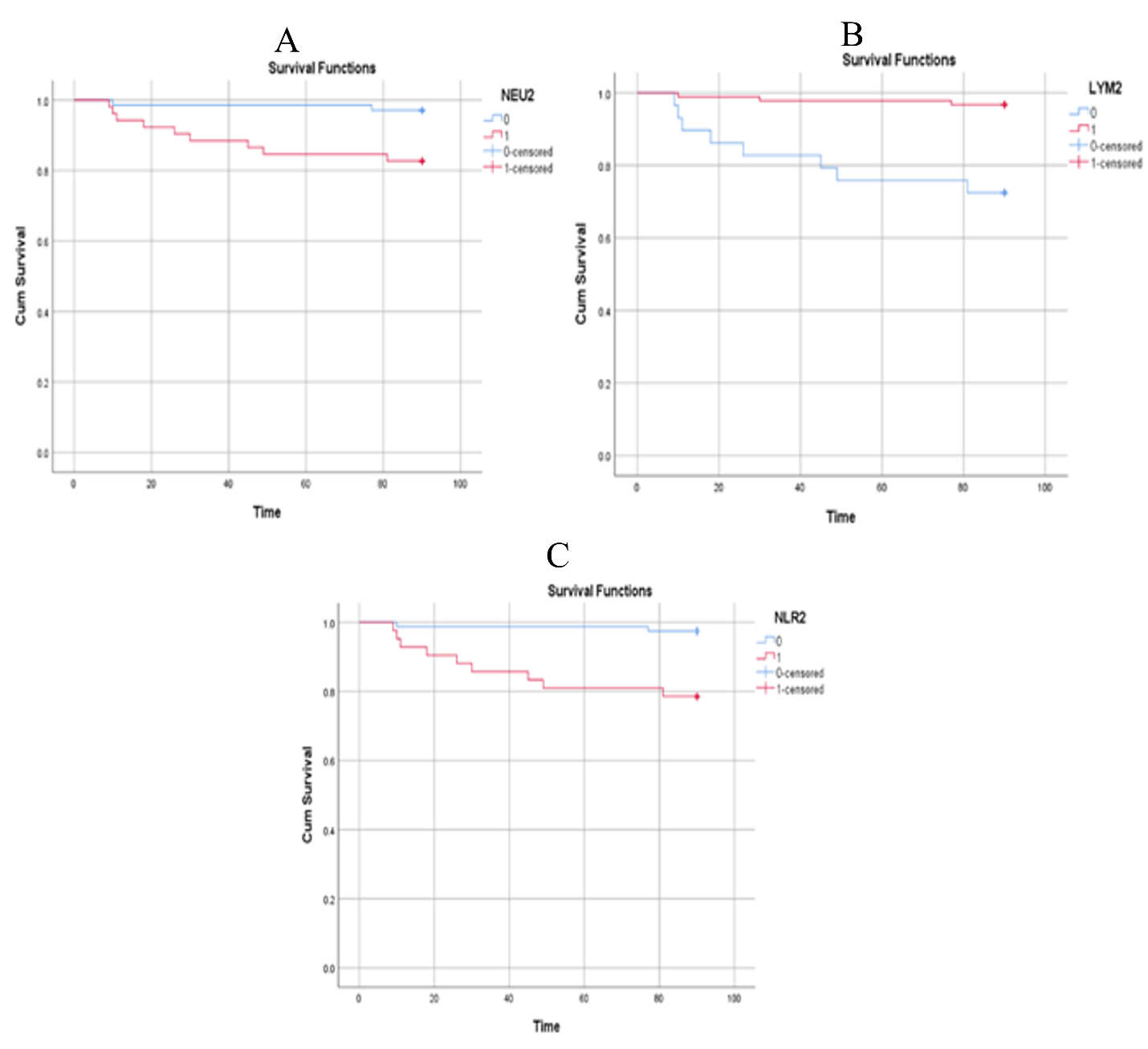

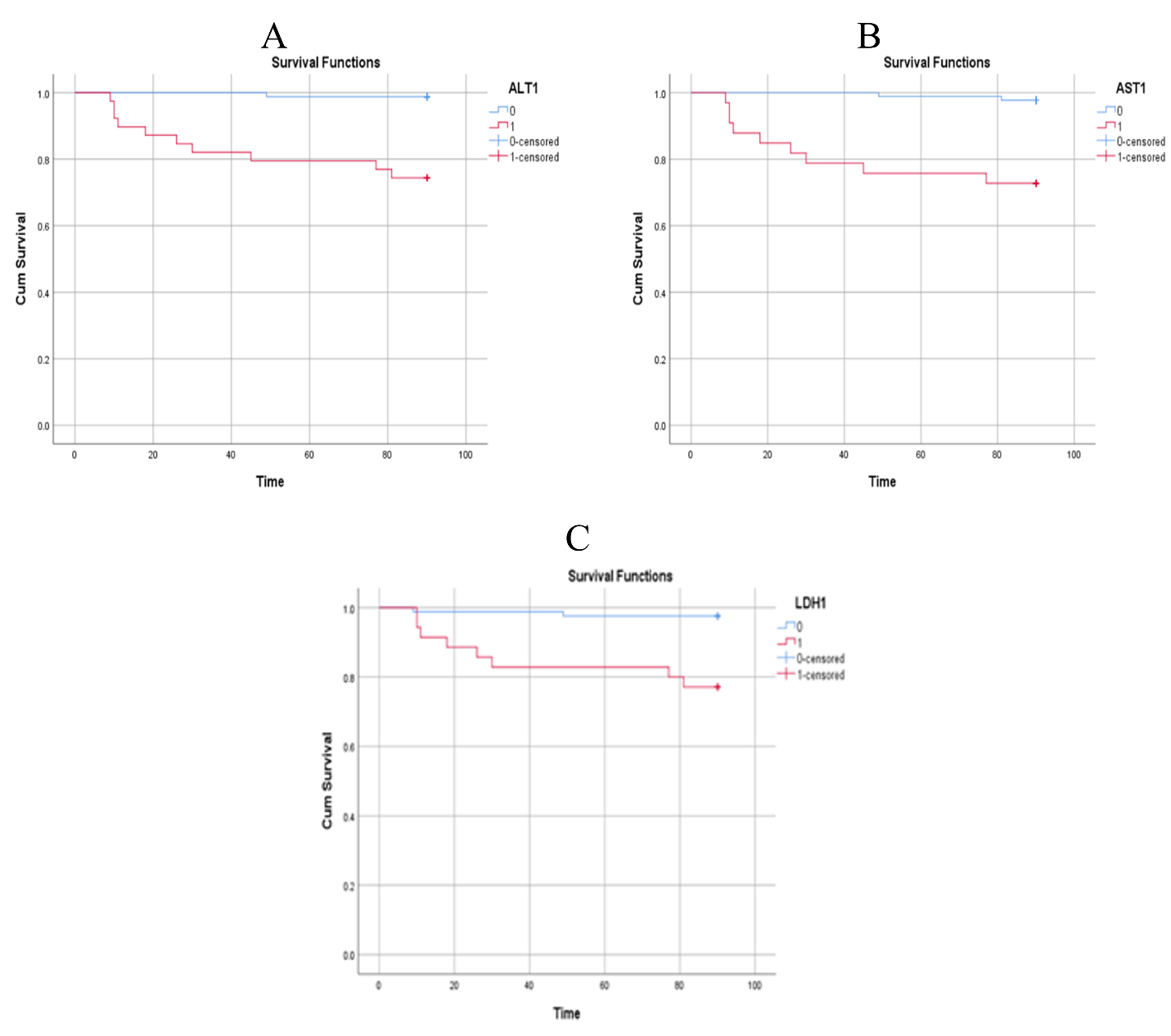

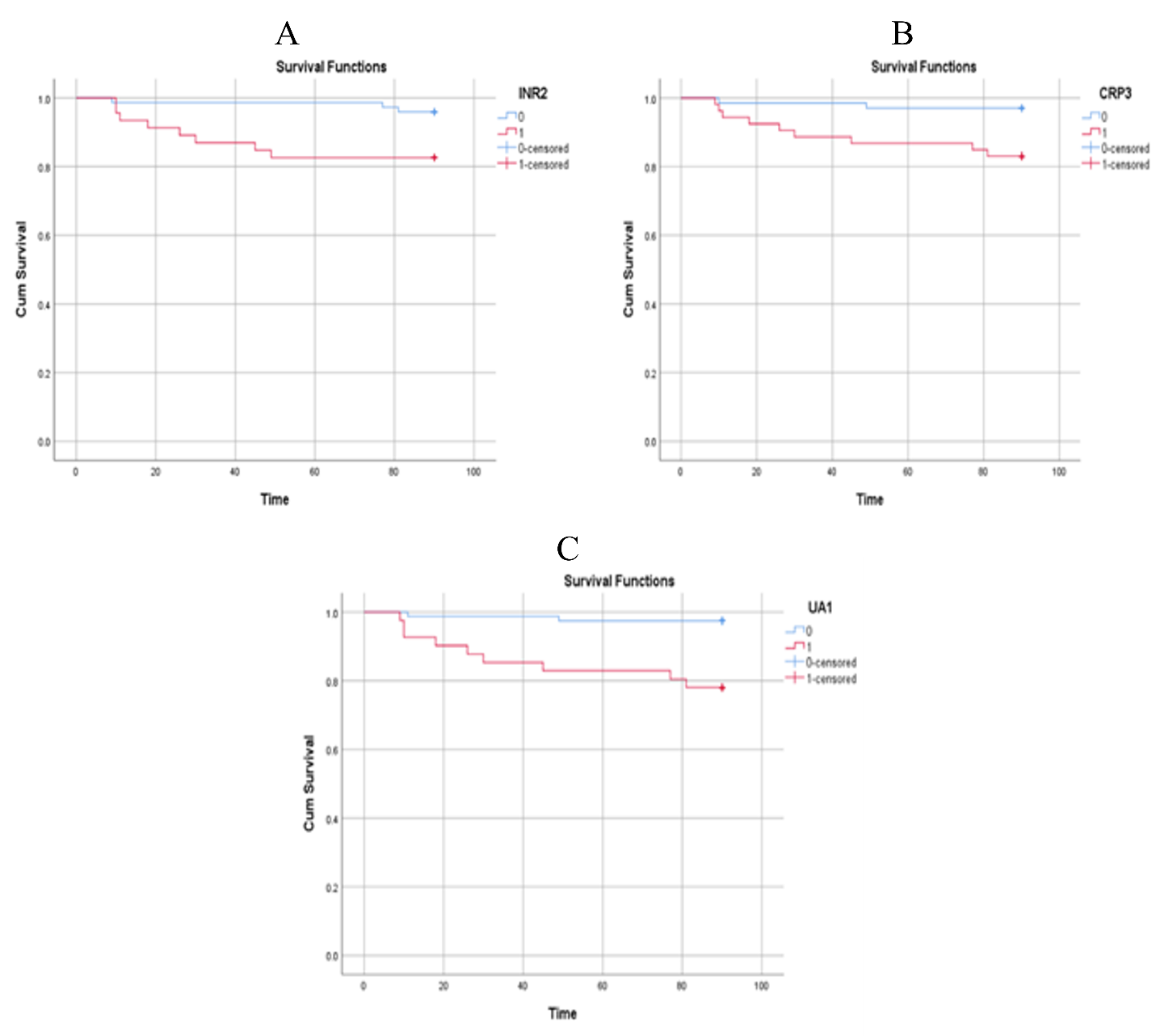

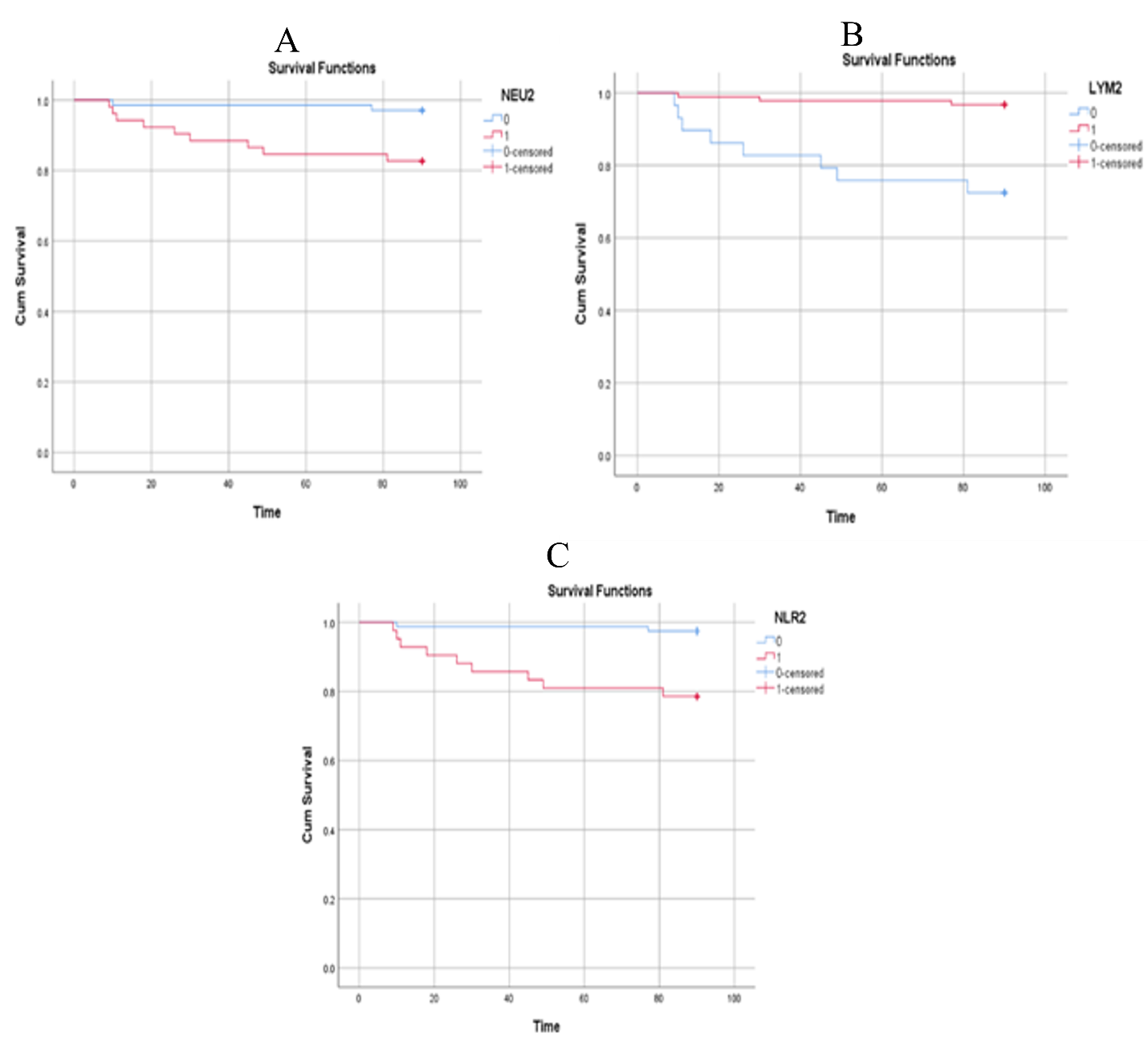

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of the significant biochemical variables determined cut-off values that maximized sensitivity and specificity for predicting 3-month post-LDLT survival. Using these thresholds, patients were stratified into two groups; the findings are presented in Tables S2 and S3 of the Supplementary Material and depicted in Figure 1. The optimal cut-off values were ALT1 481 U/L; AST1 421.5 U/L; LDH1 463 U/L; INR2 1.85; CRP3 47.5 mg/L; UA1 5.25 mg/dL; Neu2 84.85 %; Lym 4.75 %; and NLR 15.83 (P < 0.05). The corresponding accuracy values for these predictors were 80.75 %, 77.6 %, 83.2 %, 71.9 %, 68.6 %, 75.2 %, 69.1 %, 76.7 %, and 74.3 % (Table S2 of the Supplementary Material).

Patient survival according to significant biochemical predictors within 3 months after LDLT is summarized in Table S3 of the Supplementary Material. For ALT, 80 patients (98.8 %) with a postoperative day (POD) 1 value <481 IU/L survived, whereas only 29 patients (74.4 %) with ALT ≥481 IU/L survived (log-rank = 19.77; P < 0.001; Figure 1A). Similarly, 85 patients (97.7 %) with AST <421.5 IU/L and 24 patients (72.7 %) with AST ≥421.5 IU/L survived (log-rank = 19.59; P < 0.001; Figure 1B). For LDH on POD1, survival rates were 97.6 % for values <463 IU/L and 77.1 % for values ≥463 IU/L (log-rank = 13.36; P < 0.001; Figure 1C). With respect to INR on POD2, survival was 95.9 % for INR <1.85 and 82.6 % for INR ≥1.85 (log-rank = 6.23; P = 0.013; Figure 2A). Higher survival was also observed in patients with CRP on POD3 <47.5 mg/L (97.0 %; log-rank = 6.96; P = 0.008) and serum uric acid on POD1 <5.25 mg/dL (97.5 %; log-rank = 13.19; P < 0.001) (Figure 2B,C). Figure 3A shows a 97.1 % survival rate for neutrophil count on POD2 <84.85 × 10/L (log-rank = 7.34; P = 0.007), whereas Figure 3B demonstrates a 96.7 % survival rate for lymphocyte count on POD2 >4.75 × 10/L (log-rank = 16.64; P < 0.001). Finally, patients with an NLR on POD2 <15.83 had a 97.4 % survival rate compared with 78.6 % for NLR ≥15.83 (log-rank = 11.96; P < 0.001; Figure 3C).

Serum levels of different biochemical parameters on postoperative days from day one to day four (1-4) in patients with and without rejection after 3 months of living donor liver transplantation

| Variable | No rejection (n = 95) | Rejection (n = 25) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AST4 | 40(30–64) | 66(44.5–95) | 0.016 |

| TB1 | 3.1(2.1-4.7) | 4.5(2.55-5.85) | 0.026 |

| TB2 | 2.4(1.5-3.6) | 4.2(2.35-6.2) | 0.004 |

| TB3 | 2.6(1.8-4.6) | 5.7(3.15-8) | 0.001 |

| TB4 | 3(1.8-4.9) | 7.5(4.3-9) | <0.0001 |

| DB2 | 1.4(0.9-2.6) | 2.7(1.2-4.7) | 0.013 |

| DB3 | 1.7(1-3.5) | 4(1.65-6.2) | 0.003 |

| DB4 | 2.1(1.2-3.4) | 6.3(2.55-7.65) | <0.0001 |

| GGT2 | 23(17-33) | 31(19-57) | 0.043 |

| INR1 | 2(1.6-2.6) | 2.3(2-2.8) | 0.039 |

Area under curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity of statistically significant variables for prediction of rejection after 3 months in patients underwent living donor liver transplantation

| Variable | AUC | Cutoff | Sensitivity% | Specificity% | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST4 | 0.657 | 53.5 | 68 | 66.3 | 0.538– 0.776 | 0.016 |

| TB1 | 0.645 | 3.85 | 68 | 69.5 | 0.516 – 0.775 | 0.026 |

| TB2 | 0.689 | 3.65 | 68 | 75.8 | 0.565 – 0.814 | 0.004 |

| TB3 | 0.712 | 4.35 | 72 | 72.6 | 0.593 – 0.831 | 0.001 |

| TB4 | 0.774 | 4.35 | 76 | 71.6 | 0.672-0.877 | <0.0001 |

| DB2 | 0.661 | 1.95 | 68 | 64.2 | 0.527-0.796 | 0.013 |

| DB3 | 0.696 | 3.1 | 68 | 71.6 | 0.577-0.815 | 0.003 |

| DB4 | 0.762 | 3.35 | 72 | 72.6 | 0.658-0.867 | <0.0001 |

| GGT2 | 0.632 | 23.5 | 68 | 55.8 | 0.501-0.763 | 0.043 |

| INR1 | 0.635 | 2.15 | 64 | 61.1 | 0.523-0.745 | 0.039 |

Simple logistic regression of some variables for prediction of rejection

| Variable | B | SE | OR | 95% CI (OR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST4 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.098 | 1.005 | 0.999– 1.012 |

| TB1 | 0.193 | 0.085 | 0.023 | 1.213 | 1.028 – 1.431 |

| TB2 | 0.263 | 0.095 | 0.006 | 1.301 | 1.079 – 1.568 |

| TB3 | 0.201 | 0.065 | 0.002 | 1.222 | 1.075– 1.390 |

| TB4 | 0.245 | 0.069 | <0.0001 | 1.277 | 1.117 – 1.461 |

| DB2 | 0.351 | 0.125 | 0.005 | 1.421 | 1.111-1.817 |

| DB3 | 0.220 | 0.077 | 0.004 | 1.246 | 1.071-1.449 |

| DB4 | 0.292 | 0.081 | <0.0001 | 1.339 | 1.141-1.570 |

| GGT2 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.41 | 1.004 | 0.994-1.014 |

| INR1 | 0.441 | 0.296 | 0.136 | 1.555 | 0.87-2.778 |

Simple Cox regression analysis of statistically significant variables for prediction of survival after 3 months in patients underwent living donor liver transplantation

| Variable | B | SE | HR | 95% CI (HR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ALT1 ALT1 > 481 |

0.001 3.167 |

<0.0001 1.049 |

<0.0001 0.003 |

1.001 23.742 |

1.001– 1.002 3.037– 185.576 |

|

AST1 AST1 > 421.5 |

0.001 2.635 |

<0.0001 0.782 |

<0.0001 0.001 |

1.001 13.945 |

1.001– 1.002 3.009 – 64.617 |

|

LDH1 LDH1 > 463 |

0.001 2.328 |

<0.0001 0.791 |

0.01 0.003 |

1.001 10.260 |

1.000– 1.002 2.177 – 48.348 |

|

INR2 INR2 > 1.85 |

1.464 1.535 |

0.435 0.677 |

0.001 0.023 |

4.323 4.642 |

1.842– 10.145 1.231– 17.506 |

|

CRP3 CRP3 > 47.5 |

0.012 1.805 |

0.004 0.782 |

0.001 0.021 |

1.012 6.082 |

1.005– 1.02 1.314– 28.157 |

|

UA1 UA1 > 5.25 |

0.547 2.299 |

0.185 0.782 |

0.003 0.003 |

1.728 9.962 |

1.202-2.485 2.151-46.128 |

|

Neu2 Neu2 > 84.85 |

0.152 1.845 |

0.059 0.782 |

0.01 0.018 |

1.164 6.326 |

1.037-1.307 1.366-29.287 |

|

Lym2 Lym2 > 4.75 |

-0.411 -2.255 |

0.139 0.677 |

0.003 0.001 |

0.663 0.105 |

0.505-0.87 0.028-0.396 |

|

NLR2 NLR2 > 15.83 |

0.051 2.219 |

0.018 0.782 |

0.005 0.005 |

1.052 9.2 |

1.016-1.09 1.987-42.6 |

Patient survival rates according to alanine aminotransferase on postoperative day 1 (ALT1) (< 481 U/L vs ≥ 481 U/L,

Patient survival rates according to international normalized ratio on postoperative day 2 (INR2) (< 1.85 vs ≥ 1.85,

Patient survival rates according to neutrophil count on postoperative day 2 (Neu2) (< 84.85 % vs ≥ 84.85 %,

Discussion

Liver transplantation (LT) remains a life-saving therapy for patients with acute or chronic liver failure, and for those with hepatic malignancies such as hepatocellular carcinoma. Nevertheless, LT can be offered to only a small proportion of candidates because of the persistent shortage of donor organs 14. Furthermore, the procedure is not invariably successful; acute graft rejection (GR) still develops in 2.7–6.9 % of recipients 14. Although multiple investigators have proposed predictive models for GR, no consensus model has been universally adopted. Therefore, the present study aimed to construct a pragmatic model to predict both GR and patient survival using a limited set of variables measured from postoperative day (POD) 1 to POD 4 and at three months after living-donor LT (LDLT).

According to our evaluation of hepatic function, assessed via aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), AST levels on postoperative day 4 (POD4) were significantly associated with three-month graft regeneration (P = 0.016) in recipients of living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT). Conversely, both AST and ALT measured on POD1 demonstrated the strongest correlation with patient survival (P = 0.004 and P = 0.006, respectively). This pattern is compatible with the well-documented kinetic profile in which ALT and AST reach their maximal concentrations on POD1 and POD2 after transplantation, respectively, followed by a progressive decline; any secondary elevation may signal graft rejection 14,15. Throughout the observation period, the trajectories of AST and ALT during graft regeneration were comparable.

Furthermore, serum concentrations of total and direct bilirubin (TB1–4 and DB2–4) were independent predictors of graft rejection (GR) three months after living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT), with the greatest statistical significance observed on post-operative day 4 (P < 0.0001). Notably, the most widely used Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score incorporates serum TB because bilirubin levels accurately reflect hepatic synthetic and excretory function 16. In grafts that ultimately fail, TB rises slowly and progressively during the clinical course. The early-post-operative TB concentration depends on the pre-transplant value; therefore, both successful and failing transplants show an initial decline, whereas only failing grafts subsequently demonstrate a gradual increase 14. Previous studies have shown that serum DB has a higher prognostic value for predicting one-week survival in patients with liver failure than TB 17. This finding is supported by the observation that direct bilirubin levels rise owing to intrahepatic cholestasis and diminished hepatic bilirubin clearance secondary to portal flow derangement 18.

C-reactive protein (CRP) is a well-established acute-phase inflammatory marker. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of patient survival indicated that serum CRP measured on postoperative day 3 (POD3) exhibited the strongest prognostic value (P = 0.016). Accordingly, CRP may have predictive utility in liver disease, although its performance is not without limitations 13. In patients with hepatic disorders, persistently elevated CRP concentrations have been shown to predict survival more accurately 19. Conversely, even in the presence of overt infection, hepatic synthesis of CRP often results in only modest serum increases 20. Moreover, no universally accepted CRP cut-off currently exists for grading disease severity in organ transplantation 21. Several host factors—including body-mass index, weight loss, smoking, alcohol consumption and diabetes—also influence circulating CRP levels 22.

Most patients with acute liver injury (ALI) exhibit coagulation abnormalities characterized by an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) 23. In our study, INR on postoperative day 1 (POD1) was significantly associated with graft rejection (P = 0.039), whereas the highest INR linked to patient survival was observed on POD2 (P = 0.004) after living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT). Consistent with these data, INR trajectories were broadly similar in functioning and non-functioning grafts; however, absolute values remained higher in non-functioning grafts from POD3 to POD7 14. The timing and magnitude of the INR peak may vary among recipients; therefore, the maximal INR recorded during the early postoperative period is clinically relevant, irrespective of the exact day on which it occurs 14. INR has been incorporated into the diagnostic criteria for liver failure because it reflects severe hepatic injury 24,25,26,27. Consequently, it is included in prognostic models that assess graft rejection and patient survival after LDLT and may serve as a readily accessible biomarker in this setting.

Furthermore, lactate has long been employed in critical care medicine and, more precisely, in liver transplantation, as a biomarker of organ-failure severity and subsequent recovery 28,29. Thus, we measured serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in patients who underwent LDLT and observed that LDH measured on postoperative day 1 (POD1) was significantly associated with patient survival (P = 0.001). However, LDH levels did not predict graft rejection (GR). In contrast, serum lactate is inexpensive, widely available, and routinely monitored after LT. Lactate concentration at the end of transplantation integrates multiple pathologic and technical factors 30. Although findings across studies are heterogeneous, lactate levels have been evaluated as a marker of graft rejection following liver transplantation in both adults and children 31,32. Golse et al. 33 prospectively evaluated the prognostic value of end-of-procedure lactate in LT recipients in 2018. Within their cohort, 90-day mortality was 2.6 %, whereas graft loss occurred in 22.4 % of patients. They concluded that terminal lactate had a strong prognostic performance for postoperative graft loss. Additionally, the investigators found that a threshold of ≥ 5 mmol L at the end of surgery discriminated between graft loss and 90-day survival.

Additionally, uric acid (UA)—a water-soluble compound that accounts for more than half of the total antioxidant capacity of human plasma and is the final product of purine catabolism—has been extensively investigated for its antioxidant properties 34. Notably, low UA concentrations may reflect the extent of initial hepatic injury and the susceptibility to subsequent reperfusion damage after liver transplantation 35. In the present study, the serum UA level measured on postoperative day 1 (POD1) yielded the highest prognostic value for 3-month survival after living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT) (ROC analysis, P = 0.013). Thus, preoperative UA concentration appears to be a promising biomarker for early prediction of graft loss after LDLT, and higher preoperative UA levels may mitigate the development of graft rejection (GR) 36.

Additionally, the neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) warrants further investigation in liver-transplant recipients 13. The NLR, a readily obtainable indicator of systemic inflammation, is derived from the differential peripheral blood count and reflects the interplay between innate and adaptive immune pathways. Persistent dysregulated inflammation is mirrored by an elevated neutrophil count, whereas the compensatory immunoregulatory response is represented by the lymphocyte count 13. In the present study, a lower NLR on post-operative day 2 (NLR₂ < 15.83) was independently associated with improved patient survival. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) and Cox regression analyses identified POD2 as the most informative time-point for predicting 3-month survival after living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT), with p-values of 0.008 and 0.005, respectively. The NLR is preferable to alternative inflammatory markers because it is inexpensive, easy to calculate, and routinely measured as part of the standard post-transplant laboratory panel 37. In agreement with our findings, Abrol et al. 13 reported that both survivors and non-survivors exhibited higher NLRs on POD1 than those obtained pre-operatively, presumably owing to the physiological stress response to surgery. Thereafter, the NLR in survivors declined steadily from POD2 onward, whereas that in non-survivors plateaued on POD1 and subsequently rose sharply until POD8 13. These data suggest that survivors mounted a more effective immunoregulatory response than non-survivors 38.

Clinically, elevated serum gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels are commonly used as a marker of hepatic dysfunction 39. However, increased GGT concentrations have also been observed in patients exhibiting vigorous parenchymal regeneration after liver transplantation (LT) 40. Thus, an early postoperative rise in GGT appears to represent a physiological response to hepatocyte proliferation, whereas a sustained elevation suggests pathological tissue stress. Experimental work has confirmed that GGT is a reliable indicator of hepatic regeneration in murine models of liver injury 40,41,42. A recent study analyzing receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curves for mean GGT values between postoperative day (POD) 7 and POD14 after LT reported that the enzyme could not discriminate between survivors and non-survivors 43. Consistent with those findings, our ROC analysis detected no association between overall survival and GGT levels measured on POD1–POD4 following living-donor LT (LDLT). Nonetheless, the current study identified a significant correlation between acute graft rejection within three months after LDLT and GGT values on POD2, with the highest statistical significance observed (P = 0.043).

Overall, although some biomarkers exhibited modest AUC values (<0.70), their statistical significance suggests a potential value as early indicators rather than definitive predictors. Given their routine availability and low cost, these parameters may aid in early postoperative risk stratification when interpreted alongside other clinical and biochemical findings. Therefore, these early indicators may help guide intensified monitoring and prompt therapeutic decision-making in patients at an increased risk of adverse graft outcomes.

Conclusions

In summary, our research demonstrates that rising levels of AST4, TB1-4, DB2-4, GGT2, and INR1 are reliable biomarkers for predicting graft rejection in patients with liver disease who undergo living-donor liver transplantation. Additionally, ALT1, AST1, LDH1, INR2, CRP3, UA1, Neu2, Lym2, and NLR2 were statistically evaluated as predictors of 3-month post-transplant survival. Thus, these novel predictive tools are simple, rapid, and inexpensive markers that may help predict postoperative complications in LDLT recipients. These markers may therefore inform clinical decision-making, including transplant allocation. Ultimately, their use could enhance patient care, minimize adverse effects associated with over- or under-immunosuppression, and improve outcomes.

Abbreviations

ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; AUC: Area Under the Curve; CI: Confidence Interval; CRP: C-Reactive Protein; DB: Direct Bilirubin; GGT: Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase; GR: Graft Rejection; HR: Hazard Ratio; INR: International Normalized Ratio; IQR: Interquartile Range; LDH: Lactate Dehydrogenase; LDLT: Living Donor Liver Transplantation; LT: Liver Transplantation; NLR: Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio; OR: Odds Ratio; POD: Postoperative Day; PS: Patient Survival; RAI: Rejection Activity Index; ROC: Receiver Operating Characteristic; TB: Total Bilirubin; UA: Uric Acid.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that there are no acknowledgments to report.

Author’s contributions

-

Mohamed Mohamed Abdel aziz and Mohamed Ali Abdelwahab: Conceptualization and study design.

-

Mohamed Mohamed Abdel aziz and Amina Mohamed Rafat El-Sayed: Clinical data acquisition, verification of patient records, and contribution to data interpretation.

-

Mohamed Mohamed Abdel aziz: Statistical analysis.

-

Weaam Gouda and Lamiaa Mageed: Visualization, writing-original draft, review, and editing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Damietta Faculty of Medicine-Al Azhar University, Egypt under approval number (DFM-IRB 00012367-25-04-007). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

No generative artificial intelligence (AI) or AI-assisted technologies were used in the writing process of this manuscript. The authors reviewed and revised the content as needed and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests related to this work.