Analysis of JAK2, TET2 and MYD88 gene mutations in BCR-ABL–negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms

- Hematology Department and Transfusion Medicine Unit, School of Medical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia

- UKM Medical Molecular Biology Institute (UMBI), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Jalan Yaacob Latif, Bandar Tun Razak, 56000 Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- Department of Biomedical Science and Physiology, School of Life Sciences, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton, WV1 1LY, UK

Abstract

Introduction: BCR-ABL-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs)—including polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET) and primary myelofibrosis (PMF)—together with myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDS/MPNs), are clinically heterogeneous chronic myeloid disorders. These entities are predominantly driven by somatic mutations in Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), calreticulin (CALR) and myeloproliferative leukemia (MPL) genes. Although JAK2 exon 12 and MYD88 mutations are reported less frequently, they may still contribute to disease pathogenesis and progression. This study aimed to investigate the mutational landscape of JAK2 (V617F and exon 12), TET2 and MYD88 in a Malaysian cohort of patients with BCR-ABL-negative MPNs or MDS/MPNs.

Methods: A total of 54 patients with BCR-ABL-negative MPNs (n = 48) or MDS/MPNs (n = 6) were prospectively enrolled between 2015 and 2018. Genomic DNA isolated from peripheral blood was analyzed by polymerase chain reaction followed by Sanger sequencing.

Results: The JAK2 V617F mutation was identified in 81.5 % of cases, including 90 % of PV, 84.6 % of ET and 80 % of PMF patients. Among the JAK2 exon 12 variants detected, D544N and c.1194+12G>A were consistently observed on repeat sequencing. These variants, previously reported by other investigators, were likewise present in our cohort, reinforcing their potential relevance to the molecular profile of MPNs. No pathogenic variants were found in TET2 exons 1 or 7. In addition, a known MYD88 intronic single-nucleotide polymorphism (rs4988457) was detected in three MPN patients (PV = 2, ET = 1), all of whom were co-mutated for JAK2 V617F and/or an exon 12 variant.

Conclusion: This study confirms the central role of JAK2 V617F in BCR-ABL-negative MPNs and documents rare but potentially significant JAK2 exon 12 co-mutations. The presence of the MYD88 rs4988457 variant supports a possible inflammatory component in MPN pathogenesis. Together, these findings underscore the value of comprehensive mutational screening and provide further insight into the molecular complexity of MPNs, with implications for diagnosis, risk stratification and the development of targeted therapies.

Introduction

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) — comprising polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF) — are rare clonal myeloid disorders originating in the bone marrow 1. These disorders are classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as BCR-ABL-negative MPNs 2 and are frequently complicated by thromboembolic events, with potential progression to myelofibrosis or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) 3. A related category, myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDS/MPNs), exhibits overlapping features of both dysplasia and myeloid proliferation 4,5.

Somatic mutations constitute a cornerstone of the pathogenesis and classification of these disorders 6. The JAK2 V617F mutation is detected in nearly all PV patients and in more than half of those with ET or PMF 7,8,9. Other driver mutations occur in the CALR and MPL genes, each converging on the JAK-STAT signaling pathway that regulates hematopoiesis 10,11. The less common JAK2 exon 12 mutation, highly specific for PV, facilitates the diagnosis of JAK2 V617F-negative patients 12,13,14. Additional mutations in ten-eleven translocation 2 (TET2), an epigenetic regulator acting downstream of JAK2 15, are particularly observed in PMF 16,17 and MDS/MPNs 5. Myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88), an adaptor protein within the Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathway, is classically associated with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM) 18, but recent studies have reported MYD88 variants in a subset of ET cases 19, raising questions about their broader role in myeloid disorders.

Aberrant activation of both JAK-STAT and TLR signaling pathways has been implicated in abnormal hematopoiesis and immune dysfunction in these disorders 20,21.

In the present study, we characterize the mutational profiles of JAK2, TET2, and MYD88 in a cohort of BCR-ABL-negative MPN and MDS/MPN patients, thereby contributing to the existing knowledge of these disease conditions.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This prospective cohort study enrolled patients treated at Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) over a three-year period (2015–2018). Eligibility criteria comprised individuals with BCR-ABL-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs)—PV, ET, and PMF—patients who subsequently progressed to secondary myelofibrosis, and those with MDS/MPNs. Diagnostic criteria followed the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues for myeloid neoplasms and acute leukaemia, 2008 edition and its 2016 revision.

Patient samples

The study enrolled patients diagnosed with either BCR-ABL-negative MPNs or MDS/MPNs who underwent JAK2 V617F mutation analysis at Hospital USM. Hematological parameters, including hemoglobin (Hb), platelet, red blood cell (RBC) and white blood cell (WBC) counts, as well as JAK2 V617F mutation status, were retrieved from the Hematology Laboratory Information System (LIS) of Hospital USM. Peripheral blood specimens from healthy controls (n = 12) were also collected. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the USM Human Research Ethics Committee guidelines (USM/JEPeM/20020079).

Genetic Analyses

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral whole blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Mutational analysis was performed on JAK2 exon 12, TET2 exons 1 and 7, and MYD88 exons 3, 4, and 5 using Sanger sequencing. Primers for JAK2 exon 12 were adopted from dos Santos et al. 2014 22, whereas primers targeting TET2 exons 1 and 7 and MYD88 exons 3–5 were designed de novo with Primer3Plus (primer3plus.com) and validated with NCBI BLAST. Target fragments were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with exTEN II PCR Master Mix (1st Base, Singapore) containing 100 ng of template DNA per reaction. Amplicons were verified on 1 % agarose gels and then sent to 1st Base (Singapore) for capillary Sanger sequencing. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are provided in Additional File—

Data and statistical analysis

Sequencing data analysis was conducted using Sequence Scanner software 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The identified sequence variations were cross-referenced with the single nucleotide polymorphism database (dbSNP) online tool to identify any existing polymorphisms. Statistical analysis was conducted utilizing the statistical software package GraphPad Prism version 9 (GraphPad Software, USA). Continuous variables are expressed as medians and ranges, whereas categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages. The comparison of continuous variables was performed using an independent t test, whereas Fisher’s exact test was applied for categorical variables. A p value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Demographics and Hematological Profiles

In this prospective study, a total of 54 patients were enrolled, comprising 48 with BCR-ABL-negative MPNs—20 with PV, 13 with ET, 11 with PMF, and 4 with post-PV MF—and 6 with MDS/MPNs. The median age was 63 years (range, 30–90 years), with 56.3 % male predominance. Hematologic parameters varied according to disease subtype. PV patients exhibited significantly elevated RBC counts (median, 6.9 × 10/L), WBC counts (median, 15.9 × 10/L), and platelet counts (median, 520.5 × 10/L). Patients with ET had a median platelet count of 789.0 × 10/L, whereas those with PMF presented with anemia (median hemoglobin, 10.0 g/dL), lower RBC counts (median, 4.1 × 10/L), and variable leukocytosis and thrombocytosis. Compared with BCR-ABL-negative MPNs, MDS/MPN cases demonstrated higher WBC and platelet counts (p = 0.0054), consistent with the hyperproliferative phenotype of this entity. The demographic and hematologic characteristics of the patients are summarized in

Demographics and hematological profiles of

| Patient’s characteristic and hematological profiles | MPN (n=48) | PV (n=20) | ET (n=13) | MF (n=15) | p-value (PV and ET) | p-value (PV and MF) | p-value (ET and MF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gendera | |||||||

| Male | 27 (56.3) | 11 (55.0) | 7 (53.8) | 9 (60.0) | >0.9999 | >0.9999 | >0.9999 |

| Female | 21 (43.7) | 9 (45.0) | 6 (46.2) | 6 (40.0) | |||

| Age (years)b | 63.0 (30.0-90.0) | 65.0 (40.0-79.0) | 55.0 (30.0-90.0) | 61.0 (43.0-71.0) | 0.1303 | 0.2119 | 0.4737 |

| Age (years)a | |||||||

| ≤59 | 18 (37.5) | 4 (20.0) | 8 (61.5) | 6 (40.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| 60-69 | 19 (39.5) | 10 (50.0) | 2 (15.4) | 7 (46.7) | |||

| 70-79 | 9 (18.8) | 6 (30.0) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (13.3) | |||

| ≥80 | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Complete blood countsb | |||||||

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.1 (5.4-23.4) | 14.8 (8.8-23.4) | 13.4 (10.2-14.8) | 10.0 (5.4-16.5) | 0.0184* | 0.0001*** | 0.0138* |

| RBC count (x 1012/L) | 5.3 (1.9-9.4) | 6.9 (4.4-9.4) | 5.0 (3.6-5.8) | 4.1 (1.9-7.6) | <0.0001**** | <0.0001**** | 0.4196 |

| WBC count (x 109/L) | 13.7 (4.0-82.8) | 15.9 (7.1-31.3) | 10.9 (7.2-36.5) | 14.4 (4.0-82.8) | 0.3185 | 0.0465* | 0.0545 |

| Platelet count (x 109/L) | 516.0 (50.0-1752.0) | 520.5 (195.0-1388.0) | 789.0 (297.0-1611.0) | 387.0 (50.0-1752.0) | 0.0276* | 0.1725 | 0.0068** |

Demographic and hematological profiles of PMF, Post-PV MF, and MDS/MPN patients

| Patient’s characteristic and hematological profiles | PMF (n=11) | Post-PV MF (n=4) | p-value (PMF and post-PV MF) | MDS/MPN (n=6) | p-value (MDS/MPN and MPN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gendera | |||||

| Male | 6 (54.5) | 3 (75.0) | 0.6044 | 3 (50.0) | >0.9999 |

| Female | 5 (45.5) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (50.0) | ||

| Age (years)b | 62.0 (43.0-71.0) | 61.0 (55.0-68.0) | 0.7009 | 62.0 (54.0-70.0) | 0.7772 |

| Age (years)a | |||||

| ≤59 | 5 (45.5) | 1 (25.0) | NA | 3 (50.0) | NA |

| 60-69 | 4 (36.4) | 3 (75.0) | 2 (33.3) | ||

| 70-79 | 2 (18.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | ||

| ≥80 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Complete blood countsb | |||||

| Hb (g/dL) | 9.1 (5.4-14.3) | 11.8 (5.4-14.0) | 0.9754 | 11.4 (5.4-14.3) | 0.1509 |

| RBC count (x 1012/L) | 4.1 (1.9-6.9) | 4.8 (3.9-7.6) | 0.1944 | 4.4 (1.1-6.8) | 0.0694 |

| WBC count (x 109/L) | 12.1 (4.0-82.8) | 26.9 (9.0-55.6) | 0.7971 | 18.2 (3.2-318.7) | 0.0054** |

| Platelet count (x 109/L) | 367.0 (50.0-717.0) | 500.0 (385.0-1752.0) | 0.0549 | 699.5 (241.0-1197.0) | 0.9838 |

Mutation Profiling

JAK2 V617F Mutation

JAK2 V617F was identified in 44 patients (81.5%), including 18 with PV (90.0%), 11 with ET (84.6%), 12 with PMF (80.0%), and three with MDS/MPN (50.0%). In PV, mutation-positive individuals exhibited significantly higher platelet counts than mutation-negative counterparts (median 589.0 vs. 207.5 × 10/L; p = 0.0359;

Comparison of demographics, hematological and mutation profiles in

| Patient’s characteristic hematological and mutation profiles | p-value (MDS/MPN) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV (n=18) | ET (n=11) | MF (n=12) | MDS/MPN (n=3) | PV (n=2) | ET (n=2) | MF (n=3) | MDS/MPN (n=3) | |||||

| Gendera | ||||||||||||

| Male | 9 (50.0) | 7 (63.3) | 6 (50.0) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100.0) | 2 (66.7) | 0.4789 | 0.1293 | 0.5147 | >0.9999 |

| Female | 9 (50.0) | 4 (36.4) | 6 (50.0) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | ||||

| Age (years)b | 65.5 (40.0-79.0) | 59.0 (37.0-90.0) | 61.5 (43.0-71.0) | 67.0 (54.0-70.0) | 59.5 (58.0-61.0) | 30.5 (30.0-31.0) | 56.0 (47.0-63.0) | 57.0 (55.0-68.0) | 0.5165 | 0.0469* | 0.3184 | 0.5951 |

| Age (years)a | ||||||||||||

| ≤59 | 3 (16.7) | 6 (54.5) | 5 (41.7) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100.0) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 60-69 | 9 (50.0) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (41.7) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | ||||

| 70-79 | 6 (33.3) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (16.6) | 1 (33.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| ≥80 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Complete blood countsb | ||||||||||||

| Hb (g/dL) | 14.7 (8.8-23.4) | 13.4 (10.2-14.8) | 10.4 (5.4-16.5) | 12.7 (10.0-13.8) | 19.4 (17.6-21.2) | 11.9 (10.6-13.1) | 8.8 (8.4-11.1) | 7.7 (5.4-14.3) | 0.1260 | 0.5225 | 0.6012 | 0.3541 |

| RBC count (x 1012/L) | 6.9 (4.4-9.4) | 5.0 (3.6-5.8) | 4.3 (1.9-7.6) | 5.0 (4.5-6.8) | 6.6 (6.2-7.0) | 4.2 (4.1-4.4) | 4.1 (2.5-4.2) | 3.1 (1.1-4.3) | 0.4535 | 0.2537 | 0.3320 | 0.0934 |

| WBC count (x 109/L) | 15.9 (8.2-31.3) | 12.4 (7.2-36.5) | 26.9 (7.8-82.8) | 23.4 (13.0-49.9) | 12.6 (7.1-18.2) | 7.5 (7.4-7.7) | 8.5 (4.0-14.4) | 10.5 (3.2-318.7) | 0.7492 | 0.2785 | 0.1387 | 0.4765 |

| Platelet count (x 109/L) | 589.0 (363.0-1388.0) | 867.0 (297.0-1611.0) | 446.0 (80.0-1752.0) | 723.0 (367.0-1197.0) | 207.5 (195.0-220.0) | 487.0 (472.0-502.0) | 231.0 (50.0-271.0) | 680.0 (241.0-719.0) | 0.0359* | 0.1160 | 0.1960 | 0.4915 |

| Gene mutationsa | ||||||||||||

| 8 (44.4) | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4737 | >0.9999 | 0.2000 | >0.9999 | |

| 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | >0.9999 | >0.9999 | >0.9999 | >0.9999 | |

| 2 (11.1) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | >0.9999 | >0.9999 | >0.9999 | >0.9999 | |

JAK2 Exon 12 Mutation

JAK2 exon 12 mutations, D544N and c.1194+12G>A, were detected in six patients (11.1%): five with PV and one with ET. A compound mutation involving both D544N and c.1194+12G>A was identified in one PV patient (PV3) (Additional File S2), whereas an isolated D544N mutation was observed in another PV patient (PV5) (Additional File S3); the latter finding was confirmed on repeat sequencing. The c.1194+12G>A mutation alone was detected in four patients (three with PV and one with ET) (Additional Files S5, S6, S7, and S9); this result was likewise confirmed in a second sequencing run. The allelic and predicted amino-acid sequences of the wild-type gene and the identified JAK2 exon 12/intron 12 variants are presented in

Allele and predicted amino acid sequences of wild-type and detected

| Exon 12 | Intron 12 | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | ATG | AAC | CAA | ATG | GTG | TTT | CAC | AAA | ATC | AGA | AAT | GAA | GAT | TTG | ATA | TTT | GTA | AGT | CAT | TAG |

| M | N | Q | M | V | F | H | K | I | R | N | E | D | L | I | F | - | - | - | - | |

| V1 | ATA | AAC | CAA | ATG | GTG | TTT | CAC | AAA | ATC | AGA | AAT | GAA | GAT | TTG | ATA | TTT | GTA | AGT | CAT | TAG |

| M532I | I | N | Q | M | V | F | H | K | I | R | N | E | D | L | I | F | - | - | - | - |

| V2 | ATG | AAC | CAA | AGG | GTG | TTT | CAC | AAA | ATC | AGA | AAT | GAA | GAT | TTG | ATA | TTT | GTA | AGT | CAT | TAG |

| M535R | M | N | Q | R | V | F | H | K | I | R | N | E | D | L | I | F | - | - | - | - |

| V3 | ATG | AAC | CAA | ATG | GGG | TTT | CAC | AAA | ATC | AGA | AAT | GAA | GAT | TTG | ATA | TTT | GTA | AGT | CAT | TAG |

| V536G | M | N | Q | M | G | F | H | K | I | R | N | E | D | L | I | F | - | - | - | - |

| V4 | ATG | AAC | CAA | ATG | GTG | TTT | CAC | AAA | ATC | AAA | AAT | GAA | GAT | TTG | ATA | TTT | GTA | AGT | CAT | TAG |

| R541K | M | N | Q | M | V | F | H | K | I | K | N | E | D | L | I | F | - | - | - | - |

| V5 | ATG | AAC | CAA | ATG | GTG | TTT | CAC | AAA | ATC | AGA | AAT | GAA | AAT | TTG | ATA | TTT | GTA | AGT | CAT | TAG |

| D544N | M | N | Q | M | V | F | H | K | I | R | N | E | N | L | I | F | - | - | - | - |

| V6 | ATG | AAC | CAA | ATG | GTG | TTT | CAC | AAA | ATG | AGA | AAT | GAA | GAT | TTG | ATA | TTT | GTA | AGT | CAT | TAA |

| c.1194+12G>A | M | N | Q | M | V | F | H | K | I | R | N | E | D | L | I | F | - | - | - | - |

| V7 | ATG | AAC | CAA | AGG | TGT | TTC | ACA | AAA | TCA | GAA | ATG | AAG | ATT | TGA | TAT | TTG | TAA | GTC | ATT | AGA |

| c.1157delT | M | N | Q | R | C | F | T | K | S | E | M | K | I | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| V8 | ATG | AAC | CAA | ATG | GGT | TTC | ACA | AAA | TCA | GAA | ATG | AAG | ATT | TGA | TAT | TTG | TAA | GTC | ATT | AGA |

| c.1160delT | M | N | Q | M | G | F | T | K | S | E | M | K | I | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

TET2 Mutation

No mutations were detected in exons 1 or 7 of TET2 in our study cohort.

MYD88 Mutation

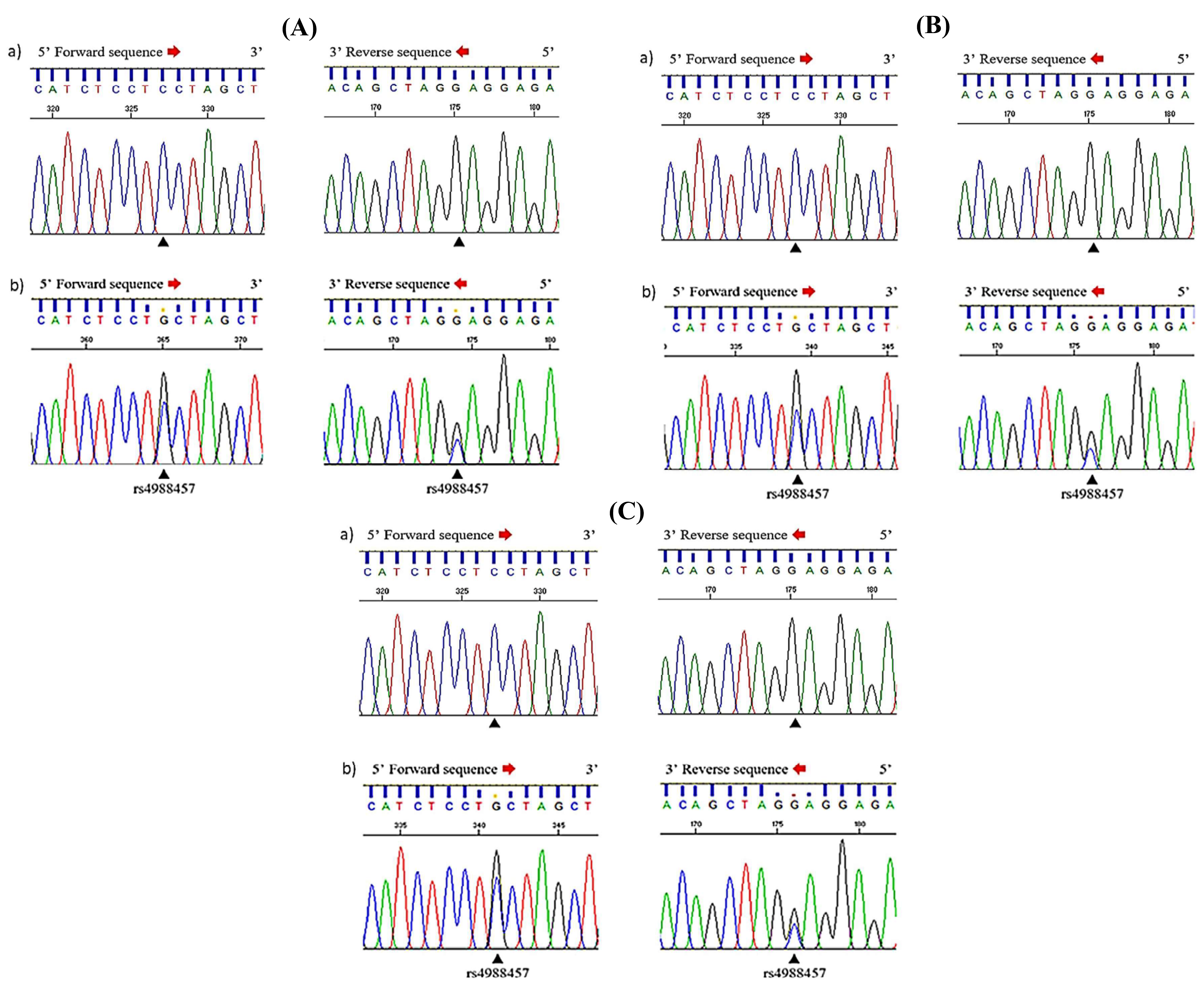

We detected an intronic SNP, rs4988457 (1944C>G), in three MPN patients (PV = two patients; ET = one patient) (Figure 1A, 1B, 1C), all co-mutated with JAK2 V617F and/or exon 12. No MYD88 variants were found in PMF or MDS/MPNs. Correlation study with hematological parameters observed no significant differences between MYD88-positive and MYD88-negative patients within the PV and ET groups (

Chromatograms showing the MYD88 rs4988457 (1944C>G) intronic variant. Sequencing analysis of MYD88 gene in (A) PV6, (B) PV11, and (C) ET8 patients with BCR-ABL-negative MPNs. a) Chromatogram in a normal control, b) Detection of the intronic variant rs4988457 (1944C>G), indicated by the arrowhead, confirmed through both forward (5→3) and reverse (3→5) sequencing.

Comparison of demographics, hematological and mutation profiles in

| Patient’s demographics, hematological and mutation profiles | MYD88-positive | MYD88-negative | p-value (PV) | p-value (ET) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV (n=2) | ET (n=1) | PV (n=18) | ET (n=12) | |||

| Gendera | ||||||

| Male | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (55.6) | 7 (58.3) | >0.9999 | 0.4615 |

| Female | 1 (50.0) | 1 (100.0) | 8 (44.4) | 5 (41.7) | ||

| Age (years)b | 69.0 (66.0-72.0) | 42.0 | 64.5 (40.0-79.0) | 57.0 (30.0-90.0) | 0.4006 | 0.5000 |

| Age (years)a | ||||||

| ≤59 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 4 (22.2) | 7 (58.3) | NA | NA |

| 60-69 | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (50.0) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| 70-79 | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (27.8) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| ≥80 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| Complete blood countsb | ||||||

| Hb (g/dL) | 17.5 (16.4-18.6) | 13.4 | 14.7 (8.8-23.4) | 13.3 (10.2-14.8) | 0.4394 | 0.6588 |

| RBC count (x 1012/L) | 6.6 (6.2-7.1) | 4.6 | 6.9 (4.4-9.4) | 5.0 (3.6-5.8) | 0.7531 | 0.8508 |

| WBC count (x 109/L) | 14.5 (10.4-18.5) | 7.2 | 15.9 (7.1-31.3) | 11.7 (7.2-36.5) | 0.7586 | 0.4428 |

| Platelet count (x 109/L) | 759.0 (475.0-1043.0) | 867.0 | 520.5 (195.0-1388.0) | 779.0 (297.0-867.0) | 0.5238 | 0.9136 |

| Gene mutationsa | ||||||

| JAK2 V617F | 2 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 16 (88.9) | 10 (83.3) | >0.9999 | >0.9999 |

| JAK2 exon 12 | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (38.9) | 3 (25.0) | 0.1895 | >0.9999 |

| TET2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | >0.9999 | >0.9999 |

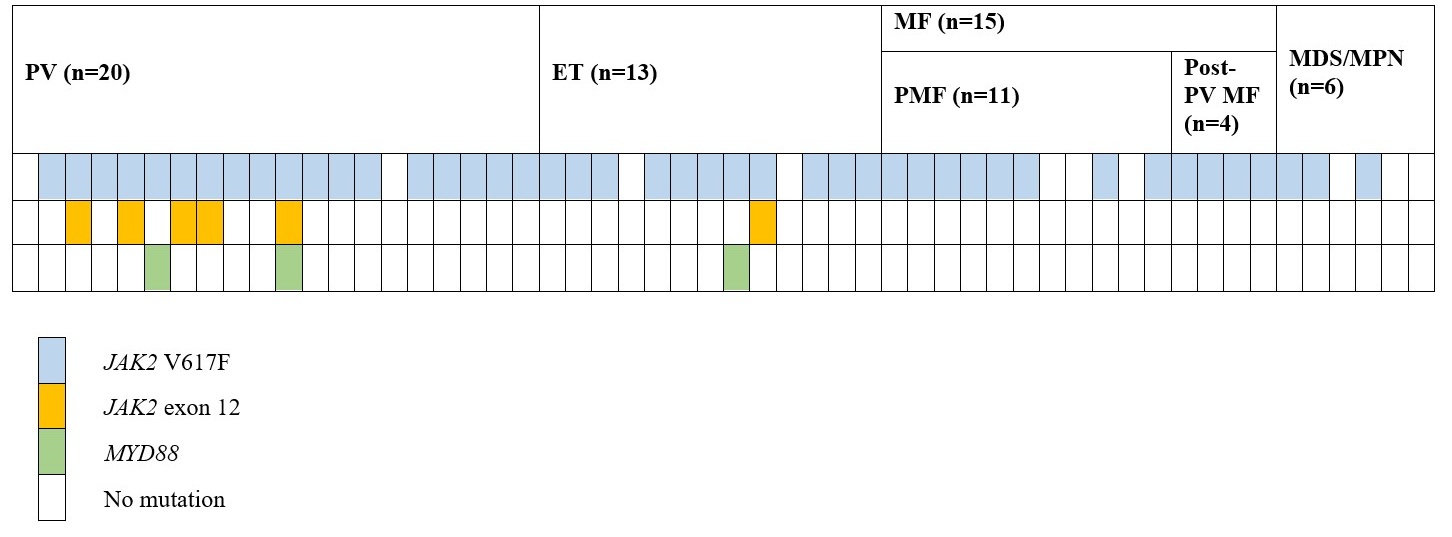

Mutation distribution. Mutation distribution across BCR-ABL-negative MPN and MDS/MPN subtypes. Each column represents an individual patient categorized by diagnostic subgroup: polycythemia vera (PV) (1-20), essential thrombocythemia (ET) (1-13), primary myelofibrosis (PMF) (1-11), post-PV myelofibrosis (Post-PV MF) (1-4), and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDS/MPN) (1-6). The presence of specific mutations is indicated by color: JAK2 V617F (blue), JAK2 exon 12 (orange), and MYD88 (green). TET2 mutation was not detected in this dataset. White boxes denote patients with no detectable mutations. The distribution highlights the predominance of JAK2 V617F mutations and the limited presence of JAK2 exon 12 and MYD88 variants.

Discussion

This study evaluates the mutation profile of JAK2 V617F, JAK2 exon 12, TET2 and MYD88 among MPN and MDS/MPN patients.

JAK2 V617F mutation

The high prevalence of JAK2 V617F in our cohort (81.5%) is consistent with its well-established diagnostic value in BCR-ABL-negative MPNs according to WHO criteria 23,24. A separate Malaysian series documented the mutation in 73.6% of patients with MPN 25. Relative to neighbouring populations, the frequency was lower in Thailand (32.9%) 26, comparable in Singapore (77.5%) 27, and ranged from 56% to 67% in Chinese cohorts 28,29,30. The markedly elevated platelet counts observed in PV cases harbouring JAK2 V617F imply a higher thrombotic risk, in line with previous evidence of JAK2-driven platelet activation 31,32,33. Among patients with ET, mutation-positive individuals were significantly older, supporting an age-related accumulation of the mutation as reported in earlier studies 34,35. Although earlier publications demonstrated significant differences in haematological indices between MDS/MPN patients stratified by JAK2 status 36, the present work detected no such differences, probably because of the small sample size (n = 6). Overall, the robust association between JAK2 V617F and BCR-ABL-negative MPNs underscores its diagnostic and prognostic importance, although its precise relationship with clinical phenotype and thrombosis remains incompletely defined 17,37,38,39.

JAK2 exon 12 mutation

The analysis revealed that six patients (five with PV and one with ET) harbored a JAK2 exon 12 mutation. Worldwide, JAK2 exon 12 mutations account for approximately 2–5 % of PV cases, occur almost exclusively in JAK2-V617F–negative disease, and are exceedingly rare in ET/PMF and MDS/MPN 40,41.

Among the identified variants, D544N and c.1194+12G>A were consistently detected in repeat sequencing runs, suggesting that these variants are highly reliable. Previous literature has documented more than ten distinct sequence variations within the JAK2 exon 12 region, the majority of which cluster between codons 536 and 544 42, which is a recognized mutation hotspot 43,44,45. Mutations occurring in this region may disrupt the JH2 pseudokinase domain, analogous to V617F, thereby resulting in constitutive activation of JAK–STAT signaling 46,47. Notably, alterations involving the E543–D544 sequence have been reported in multiple studies 48,49, and the specific D544N variant has been detected in the Chinese population 28. The c.1194+12G>A variant, located 12 nucleotides downstream of exon 12 within intron 12, lies in close proximity to a previously described variant, c.1194+6T>C, identified in the same genomic region 22.

Interestingly, all JAK2 exon 12-positive cases also harbored the JAK2 V617F mutation. This co-occurrence is atypical, as exon 12 mutations are generally considered mutually exclusive with V617F in classical MPNs 50. Nonetheless, familial and complex PV cases with such co-mutations have been reported 48,51. A study from Qatar (Western Asia) likewise reported a high frequency of JAK2 exon 12 mutations in PV and ET that co-occurred with JAK2 V617F 52, suggesting possible geographical variation. The co-detection of JAK2 V617F and exon 12 variants may indicate subclonal heterogeneity arising from clonal mosaicism and disease evolution, although such events are rare 53. Because our analysis relied on Sanger sequencing—which is less sensitive than next-generation sequencing (NGS) and susceptible to artefacts—accurate quantification of low-level variant allele frequencies (VAF < 15–20 %) was not feasible. Accordingly, definitive conclusions cannot be drawn, and this observation warrants further investigation.

TET2 mutation

A recent meta-analysis reported TET2 mutation prevalences of 20.8 % in Asia, 17.4 % in North America, 13.0 % in Europe, and 7.0 % in Australia 54. Although TET2 is a common epigenetic modifier in MPNs, we did not detect mutations in exons 1 or 7 within our cohort. This observation aligns with prior studies demonstrating that pathogenic variants cluster predominantly in exons 3 and 11 55. Exon 1 contains promoter sequences that regulate gene expression, whereas exon 7 resides within a conserved domain. The absence of variants in these exons may therefore reflect either a low mutation frequency or epigenetic silencing mechanisms that are not detectable by conventional sequencing 56,57,58. Moreover, previous reports suggest that TET2 mutations alone are insufficient to initiate the MPN phenotype, although they may facilitate genomic instability and disease progression 3. The apparent absence of TET2 variants in our series may thus stem from the restricted exon coverage rather than their true biological absence. Comprehensive sequencing of the entire coding region will therefore be required to delineate the full TET2 mutational landscape.

MYD88 mutation

We identified three patients with MPNs—two with PV and one with ET—harboring the rare rs4988457 (c.1944C>G) MYD88 variant. Consistent with previous reports, MYD88 mutations are exceedingly uncommon in BCR-ABL–negative MPNs. In large sequencing series, including a cohort of 303 individuals, no MYD88 alterations were detected 59, with the exception of a single ET case complicated by Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM), in which a MYD88 variant was observed 19. Accordingly, our study is among the first to evaluate MYD88 mutations in BCR-ABL-negative MPNs and in MDS/MPN overlap syndromes. Although the pathobiological significance of rs4988457 remains undefined, MYD88 aberrations have been implicated in multiple other hematologic malignancies, including T-cell lymphomas 60, activated B-cell–type diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (ABC-DLBCL) 61, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) 62, and AML 63.

Conclusions

This report provides insights into the mutational landscape of BCR-ABL-negative MPNs and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDS/MPNs) in a Malaysian cohort, with an emphasis on JAK2, TET2, and MYD88 alterations. The overall mutational profile is illustrated in Figure 2. The high prevalence of the JAK2 V617F mutation confirms its pivotal diagnostic role across PV, ET, PMF, and MDS/MPNs. JAK2 exon 12 variants, specifically D544N and c.1194+12G>A, previously reported in other studies, were likewise identified in our cohort. Finally, identification of the intronic MYD88 variant rs4988457 in three MPN cases suggests a potential inflammatory contribution to MPN pathogenesis and warrants further investigation.

Consent

The study protocol was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of University Sains Malaysia (USM) (Reference number: USM/JEPeM/20020079). Informed consent was obtained from the MPN and MDS/MPN patients prior to sample collection.

Abbreviations

ABC-DLBCL: Activated B-cell diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; AML: Acute myeloid leukemia; BCR-ABL: Breakpoint cluster region–Abelson proto-oncogene; BM: Bone marrow; CALR: Calreticulin; c.1194+12G>A: Intronic substitution in the JAK2 gene, where guanine (G) is replaced by adenine (A) at 12 nucleotides downstream of coding position 1194 (intron 12); CLL: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia; D544N: Aspartic acid (D) to Asparagine (N) substitution at codon 544 of the JAK2 gene; ET: Essential thrombocythemia; Hb: Hemoglobin; JAK2: Janus kinase 2; MF: Myelofibrosis; MPL: Myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene; MPN: Myeloproliferative neoplasm; MDS/MPN: Myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm; MYD88: Myeloid differentiation primary response 88; NGS: Next-generation sequencing; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; PMF: Primary myelofibrosis; Post-PV MF: Post-polycythemia vera myelofibrosis; PV: Polycythemia vera; RBC: Red blood cell; SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism; TLR: Toll-like receptor; VAF: Variant allele frequency; V617F: Valine (V) at amino acid position 617 is replaced by Phenylalanine (F); WBC: White blood cell; WHO: World Health Organization; WM: Waldenström's macroglobulinemia

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of the laboratory staff at the Department of Hematology, School of Medical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), and Hospital USM.

Author’s contributions

M.R, M.A.I and M.F.J conceptualized the study and designed the methodology, Y.C.C performed the data collection, M.J.S.A and Y.C.C performed the data analysis and wrote the main manuscript text, M.J.S.A wrote the final manuscript revision, M.J.S.A and M.A.I checked for intellectual content and editing. M.R, R.H, and M.F.J supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Research University Grant (No. 1001/PPSP/812187), Universiti Sains Malaysia.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that they have not used generative AI (a type of artificial intelligence technology that can produce various types of content including text, imagery, audio and synthetic data. Examples include ChatGPT, NovelAI, Jasper AI, Rytr AI, DALL-E, etc) and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process before submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.