Transitioning from conventional therapies to nanomedicine-based therapeutics for major depressive disorder

- Department of Biotechnology, Saveetha School of Engineering, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS), Saveetha Nagar, Thandalam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu – 602105, India

- Medical Bionanotechnology, Faculty of Allied Health Sciences (FAHS), Chettinad Hospital & Research Institute (CHRI), Chettinad Academy of Research and Education (CARE), Kelambakkam, Chennai, TN-603013, India

- Medical Bionanotechnology Lab, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Centre for Global Health Research, Saveetha Medical College, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Thandalam, Chennai, 602105, India

Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common, debilitating psychiatric disorder characterized by persistent sadness, anhedonia, and functional impairment, affecting millions of individuals worldwide and constituting a leading cause of disability. This review summarizes conventional approaches for the prevention and treatment of MDD, encompassing pharmacotherapy with various classes of antidepressants and psychotherapeutic interventions such as cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT). Although these interventions demonstrate efficacy, their clinical utility is frequently constrained by delayed onset of action, adverse effects, and partial or absent response in a substantial proportion of patients. Nanomedicine has emerged as a promising therapeutic avenue for MDD; it entails the use of neuro-targeted nanoparticles to enhance drug bioavailability. Such nanosystems may overcome limitations of conventional therapies by enabling spatiotemporally controlled release of antidepressants within the brain. Nevertheless, before widespread clinical adoption, the safety profile, long-term sequelae, and complex biocompatibility of these materials require rigorous elucidation. The review additionally discusses the contribution of animal models, particularly zebrafish, to neurobiological investigations of depression. Such models are indispensable for recapitulating depressive phenotypes, delineating MDD pathophysiology, and assessing candidate therapeutics, including nanomedicines. In conclusion, although established MDD therapies remain fundamental, nanomedicine offers substantial promise; however, additional research and optimization are imperative to ensure its safe and efficacious clinical translation.

Introduction

The term ‘depression’ encompasses multiple concepts: transient low mood is common and often physiologic, whereas Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) denotes a distinct, severe, and clinically diagnosable illness. MDD affects mood, energy, sleep, appetite, cognitive function, psychomotor activity, and frequently induces pervasive guilt and worthlessness. The presence of manic or hypomanic episodes reclassifies the condition as Bipolar Disorder, while episodes limited to depression define Unipolar Depression. Although the DSM-IV (and DSM-5) provide operational diagnostic criteria for MDD, the disorder exhibits marked heterogeneity in symptomatology, trajectory, and treatment responsiveness; consequently, diagnostic boundaries remain porous. Debate persists as to whether MDD represents a discrete disease entity or the extreme end of a continuous mood-regulation spectrum 1. In addition to profound personal morbidity, MDD imposes substantial economic costs; The Lancet Global Health estimates annual productivity losses from depression and anxiety at ≈ US$1 trillion, with cumulative costs projected to reach US$16 trillion by 2030. The absence of fully effective treatments partly reflects incomplete elucidation of depressive pathophysiology, which spans monoaminergic dysregulation, altered neurogenesis, neuroinflammation, stress-axis dysfunction, and associated neurochemical, immunological, and anatomical changes. Key mechanistic domains include perturbed neurotransmitter levels, structural brain alterations, neuroinflammatory processes, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation, impaired neurogenesis, and disrupted neuroplasticity 2. Early hypotheses focused on serotonergic deficiency, but the monoamine theory was subsequently broadened to implicate three principal neurotransmitters—serotonin (5-HT), dopamine (DA), and noradrenaline (NA)—in mediating depressive symptomatology. Beyond neurochemistry, alterations in grey- and white-matter volumes and other macrostructural brain changes have been documented. Neuroimaging demonstrates volumetric and functional abnormalities in the hippocampus, amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex, ventromedial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices, lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and ventral striatum—regions integral to mood and stress regulation 3. Psychotherapeutic interventions, ranging from classical psychoanalysis to contemporary modalities, constitute core treatment options, differentiated primarily by theoretical orientation and technique. Psychoanalysis seeks to elucidate unconscious conflicts, whereas the umbrella term ‘psychotherapy’ encompasses diverse evidence-based methods such as cognitive therapy, behavioural therapy, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), dialectical behaviour therapy, psychodynamic therapy, and interpersonal therapy. While psychoanalysis may benefit selected patients, it is frequently criticised for limited empirical support. Conversely, many psychotherapies enjoy stronger empirical validation yet face practical barriers. Access can be constrained by cost and, in some settings, by concerns regarding confidentiality. Ultimately, therapeutic outcome depends on patient engagement and therapist competence 4.

Besides psychotherapy, antidepressant medications represent an additional therapeutic option for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). The predominant theoretical basis for antidepressant development is the monoamine hypothesis, which posits that symptom relief results from inhibition of neurotransmitter reuptake. Among the various classes of these agents, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are generally considered first-line therapies. Norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs) are classified as atypical antidepressants that predominantly affect dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine (NE) neurotransmission in the brain. These agents are employed to alleviate depressive and anxiety symptoms and to manage certain attentional disorders. NDRIs block the reuptake of NE and DA at presynaptic terminals, thereby increasing synaptic concentrations of these neurotransmitters and enhancing neurotransmission, which can elevate mood and improve cognitive clarity 5. Unlike SSRIs and SNRIs, NDRIs exert minimal influence on serotonin, making them a valuable alternative for patients who do not respond to, or cannot tolerate, serotonergic drugs. Nevertheless, NDRIs are associated with adverse effects; the most common with bupropion are insomnia and xerostomia, while high doses may precipitate dose-dependent seizures. Consequently, careful clinical monitoring and dose optimisation are required. Overall, NDRIs provide an effective fallback strategy when conventional regimens are ineffective or poorly tolerated. At present, bupropion is the only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved NDRI—marketed as Wellbutrin for depression and Zyban for smoking cessation—and is also prescribed for MDD, seasonal affective disorder, and as an adjunct in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Its antidepressant efficacy is attributed to its dual action on NE and DA, neurotransmitters that modulate mood and motivation. Because bupropion is the sole licensed NDRI, patients requesting this class are effectively limited to this agent. The limited efficacy and safety of conventional antidepressants have stimulated interest in alternative drug-delivery strategies. Intranasal administration is promising because it bypasses the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and delivers drug directly to the central nervous system. The BBB, composed of endothelial cells, pericytes, astroglia, and mast cells, restricts CNS entry of most drugs after oral or intravenous administration; additionally, efflux transporters such as P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance proteins actively extrude antidepressants, further diminishing their intracerebral concentrations 6.

Novel drug-delivery systems, including liposomes, microemulsions, mesoporous nanoparticles, and other lipid-based carriers, have been developed to enhance the solubility, bioavailability, and absorption of pharmaceutical agents by circumventing physiological barriers. Niosomes represent a nanovesicular platform capable of crossing the blood–brain barrier (BBB); they can encapsulate both hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs and enable controlled release, thereby making them particularly suitable for brain-targeted therapy. Compared with liposomes, niosomes are more stable and less expensive because they are assembled from non-ionic surfactants 7. Owing to their small size and modifiable surface chemistry, niosomes can penetrate the brain directly, and receptor-mediated transport may confer improved therapeutic efficacy with fewer adverse effects. Bilosomes and niosomes also provide prolonged drug release and can consequently improve patient compliance in neurological disorders. Zebrafish, which constitute an important model of depression because of their genetic and neurochemical homology to humans, are increasingly employed to evaluate these nanodelivery systems in vivo. The present review summarizes the limitations of conventional antidepressant therapy, discusses recent nanomedicine advances for depression, and underscores the value of the zebrafish model for developmental neurobiology and translational research. Specifically, it provides a comprehensive overview of nanomedicine applications for major depressive disorder (MDD), with emphasis on targeted antidepressant delivery, safety considerations, and findings obtained in zebrafish. By integrating preclinical data with prospective research directions, this work aims to offer a distinct and timely contribution. Drawing on conventional pharmacology, nanotechnology, and zebrafish-based neurobehavioral evidence, the review seeks to bridge mechanistic insight and translational potential.

Methodology

We conducted this narrative review to systematically present and compare nanomedicine-based therapeutic strategies with current conventional modalities for major depressive disorder (MDD). We searched PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar using combinations of the following keywords and Boolean operators appropriate to each database: “major depressive disorder,” “conventional therapy,” “antidepressant,” “nanopsychiatry,” “drug delivery,” “blood–brain barrier,” and “zebrafish model.” Publications dated 2014–2024 were prioritised to capture both foundational data and the most recent technological advances; one earlier seminal article was retained for context. Eligible studies included peer-reviewed originals and reviews addressing prevention, diagnosis, pharmacotherapy, or nanomedical interventions for depression, whereas editorials and mechanistically irrelevant articles were excluded. Relevance was established through sequential screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts. From each included study we extracted the nanoparticle type, the mechanism of blood–brain barrier traversal, zebrafish behavioural paradigms, and reported advantages over conventional therapy.

Conventional approaches

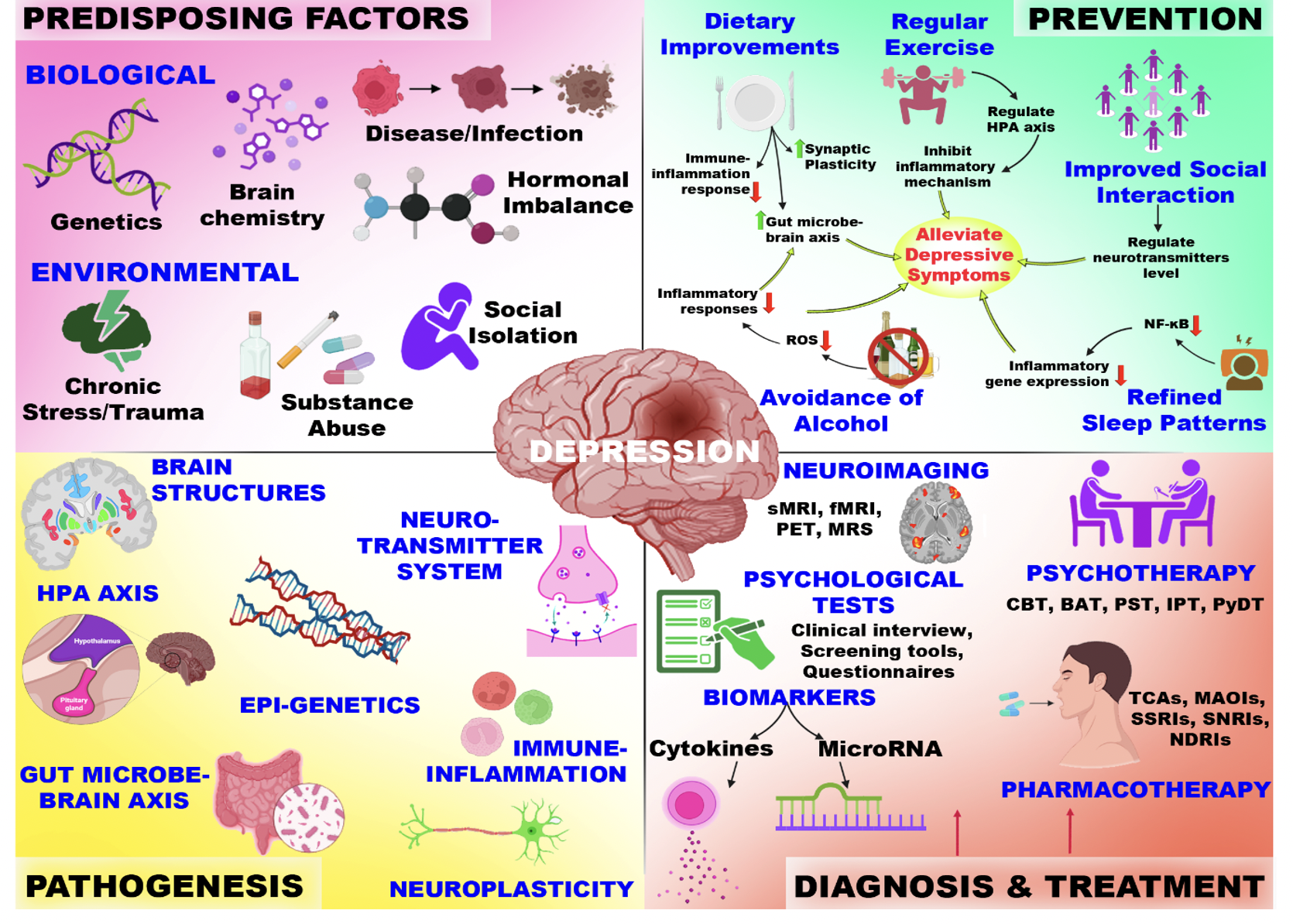

Prevention of MDD: Occurrence and recurrence

Given the substantial morbidity and global burden associated with major depressive disorder (MDD), preventive strategies are of considerable interest. Although depression cannot be completely prevented, modifications in overall lifestyle can markedly attenuate its impact 8. Lifestyle medicine—encompassing sleep hygiene, dietary patterns, regular physical activity, reduced sedentary behaviour, robust social support, and mood regulation—is summarised in Figure 1. Evidence indicates that individuals at elevated risk for MDD may lower their probability of onset and recurrence by adopting positive behaviours and sustainable lifestyle practices, underscoring the importance of proactive, preventive mental-health interventions.

Diet patterns

Dietary interventions are safe, effective, and broadly applicable means of preventing MDD by attenuating pathological inflammation. Certain nutrients possess anti-inflammatory properties, whereas diets rich in refined starches, sugars, and saturated fats and poor in fibre and omega-3 fatty acids activate pathways that maintain the body in a state of chronic inflammation, thereby increasing the risk of major depressive disorder. Adoption of a pro-inflammatory diet enhances depression risk by inducing chronic low-grade inflammation via activation of innate immune responses. Neuronal activity and synaptic plasticity are likewise modulated by such diets and may contribute to the development of MDD. Conversely, a healthy, anti-inflammatory, nutrient-dense diet can markedly reduce this risk, underscoring the integral role of nutrition in both prevention and treatment of the disorder. More importantly, the gut–microbiota–brain (GMB) axis has been implicated in MDD, because alterations in gut bacterial composition, barrier permeability, and immune-inflammatory signalling influence brain function and mood 9. Restoring eubiosis through probiotics and dietary modification therefore represents a promising therapeutic strategy. For example, a gluten-free diet supplemented with probiotics may modulate the GMB axis by attenuating immune-inflammatory mechanisms and alleviating common MDD symptoms 10. Kachlíková et al. hypothesised that a low-carbohydrate, high-fat regimen such as the ketogenic diet could promote neuroplasticity by increasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), whose expression is reduced during depression 11. Accordingly, targeting BDNF elevation via carbohydrate restriction may offer a rational approach for treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Complementing this, Zhao et al. demonstrated an inverse association between the Composite Dietary Antioxidant Index (CDAI) and depression in overweight and obese U.S. adults 12; however, this relationship plateaued at higher antioxidant intakes. Although the two studies address distinct mechanisms—BDNF-mediated neuroplasticity versus oxidative-stress reduction—both highlight the central role of diet in depression pathophysiology. Collectively, the evidence suggests that nutritional pathways, including neurotrophic and antioxidant effects, interact to promote mood regulation and resilience to depression.

The figure depicts a conceptual overview of MDD, explaining predisposing factors, such as biological and environmental, that influence the central pathogenic domains. The figure also highlights the prevention strategies based on lifestyle diagnostic tools and established therapeutic approaches in clinical practice.

Sleep patterns

Insomnia is a cardinal symptom of major depressive disorder (MDD), and its increased risk and recurrence are tightly associated with dysregulated inflammation; consequently, optimizing sleep quality may constitute a central strategy for depression prevention. Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) effectively targets maladaptive cognitions, sleep hygiene, and circadian timing to improve sleep and mood 13. In addition, circadian rhythm support (CRS), including morning bright-light exposure, regular physical activity, and passive body warming, can further enhance CBT-I effectiveness 14. Although the causal relationship between sleep disturbance and MDD has not been fully elucidated, accumulating evidence indicates that disrupted sleep alters monoaminergic neurotransmission and activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, thereby inducing hyperarousal and a pro-inflammatory state that promotes depressive pathology. Hyper-activation of the HPA axis and diminished negative feedback sensitivity have been repeatedly linked to MDD and are considered maladaptive mechanisms that perpetuate depressive symptoms. A 17-year cohort study of 5,547 older men conducted by Hill-Almeida et al. reported that sleep difficulties increased depression risk by 67 %, independent of age, education, smoking, or frailty 15. A subsequent meta-analysis of 14 studies confirmed this link with a pooled risk ratio of 1.82, emphasizing sleep as a key intervention target in older adults. Additionally, Didikoglu et al.'s longitudinal study of 6,375 participants demonstrated that depression prevalence declines until approximately 80 years of age and then rises, conferring a 10 % increase in mortality risk 16. Shorter sleep duration and early depression signs predicted future sleep disturbances. Post-mortem studies have further revealed reduced synaptic density, especially in the frontal lobe, associated with depression. Collectively, these findings highlight the imperative for early detection and integrated interventions addressing sleep disruption, depression, and cognitive decline across the ageing trajectory.

Physical activities and exercises

Physical exercise is a well-established preventive factor for cardiovascular disease, and emerging evidence also implicates it in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD). Accumulating data indicate that exercise exerts antidepressant effects through complex molecular and cellular mechanisms. For instance, physical activity up-regulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), thereby enhancing angiogenesis, delivery of neurotrophic factors, oxygen availability, synaptogenesis, and neurogenesis. These changes ultimately improve hippocampal function, a brain region critical for mood regulation and the stress response. Exercise is also associated with reduced concentrations of pro-inflammatory mediators and increased levels of anti-inflammatory molecules, further contributing to protection against MDD. Observational studies suggest that engaging in approximately 45 min of vigorous aerobic exercise—or lower-intensity yoga and stretching—on most days substantially decreases the risk of developing MDD 17. In a murine study, Su et al. demonstrated that voluntary wheel running for two weeks attenuated stress-induced learned helplessness and completely abolished kynurenine (KYN)-induced depressive-like behavior 18. Similarly, Martins et al. established a reserpine-induced zebrafish model of depression and showed that both fluoxetine and exercise reversed the associated behavioral alterations 19.

Avoidance of alcohol and drug usage

Limiting alcohol consumption and avoiding illicit drug use are crucial for reducing the risk of major depressive disorder (MDD) and preventing relapse. Excessive alcohol and drug use markedly increases the likelihood of developing or worsening depressive symptoms. In a cross-sectional study involving over 19,000 Hispanic adults, Jetelina et al. reported that individuals with MDD were nearly four times more likely to meet criteria for alcohol dependence, particularly among Puerto Ricans and Mexican Americans 20. Early onset of alcohol use further heightened the risk of MDD, while alcohol dependence was a more robust predictor of depression than binge drinking or total alcohol consumption. Pathophysiologically, alcohol disrupts neurotransmitter homeostasis, sleep patterns, and mood regulation, exacerbating depressive symptoms and potentially reducing treatment efficacy.

Building a strong social support system

The influence of social support—provided by family, friends, coworkers, and the broader community—on mental health is critical for the management and prevention of major depressive disorder (MDD). Reduced social contact and loneliness exacerbate depressive symptoms, whereas a strong perceived support network enhances stress resilience and improves treatment outcomes. In a meta-analysis of 53 studies encompassing 40,929 older adults, Wen et al. reported that loneliness was directly associated with depression, with social support and resilience acting as mediators 21. The association was stronger in samples composed of >60 % women. These findings underscore the need for policies and interventions that foster social support and resilience to mitigate depression and promote healthy ageing.

Diagnosis of MDD

Depression can be difficult to diagnose because its symptoms are heterogeneous and may even be contradictory, ranging from apathy and anhedonia to irritability as well as changes in eating or sleeping patterns. Accurate diagnosis is important because depression affects physical, emotional, cognitive, and behavioural domains, with the degree of impact varying among individuals. A thorough medical evaluation combined with family history can help differentiate between major depressive disorder (MDD), persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia), bipolar disorder, and depressive disorder not otherwise specified, thereby allowing the treatment approach to be individualized according to the patient’s clinical context. Assessment of MDD can be broadly divided into clinical evaluation and laboratory investigation. The clinical evaluation includes a thorough history of symptoms and comorbid medical conditions, along with a physical examination; additional studies—such as blood tests, neuroimaging, or other specialized investigations—may be conducted to exclude underlying conditions that can precipitate or mimic depressive symptoms.

Psychological tests and clinical interviews

Diagnosis of depression is a comprehensive process that must be conducted by a qualified healthcare professional, such as a psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, or primary care physician. Clinicians apply standardized criteria delineated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), to establish the diagnosis. The assessment typically begins with a detailed clinical interview during which the practitioner obtains information regarding the patient’s symptoms, medical and psychiatric history, and current mental status. In addition to the interview, validated screening instruments and questionnaires are routinely administered to quantify the severity and functional impact of depressive symptoms. Frequently used measures include the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Major Depression Inventory (MDI), Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), and Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD). These instruments assist in detecting core depressive features. For a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, symptoms must persist for a minimum of two weeks and cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning 22.

Neuroimaging

Advanced neuroimaging modalities, including structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI), functional MRI (fMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), are being employed to delineate the neural substrates of major depressive disorder (MDD). By interrogating the neurobiological mechanisms underlying disease pathogenesis, these approaches aim to identify biomarkers that refine diagnosis, monitor illness trajectory, and anticipate therapeutic response 23. sMRI studies consistently demonstrate region-specific anatomical alterations in MDD, most prominently within the orbitofrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex—regions integral to affective processing and decision-making. In contrast to the diffuse volumetric reductions characteristic of bipolar disorder, structural changes in MDD are largely circumscribed, with robust evidence for hippocampal atrophy and sporadic alterations in hippocampal morphology. Findings regarding amygdalar volume remain heterogeneous, likely reflecting methodological heterogeneity and sample variability. Although sMRI furnishes valuable pathophysiological insight, its stand-alone prognostic utility for treatment outcomes is limited, underscoring the necessity for multimodal models that integrate neuroimaging with clinical, demographic, and genetic variables to facilitate precision care.

Functional MRI further elucidates MDD pathophysiology by revealing aberrant connectivity within large-scale networks, most notably the default mode network (DMN), which subserves self-referential cognition and emotional regulation 24. Amygdalar hyper-responsivity observed in untreated patients frequently normalizes following effective antidepressant therapy, providing a putative neural correlate of clinical improvement. PET investigations demonstrate disturbed cerebral perfusion and glucose metabolism, particularly within the medial prefrontal cortex; these abnormalities often revert towards baseline after successful pharmacological or psychotherapeutic intervention. Nevertheless, PET assessments of 5-HT1A receptor binding have yielded inconsistent findings, highlighting the neurochemical heterogeneity of MDD. Finally, MRS offers a non-invasive means of interrogating brain biochemistry by quantifying hydrogen- and phosphorus-containing metabolites, thereby exposing neurochemical dysregulation associated with depression and deepening our understanding of its molecular underpinnings.

Biomarkers as a diagnostic tool

Biomarkers provide a convenient, cost-effective, and rapid alternative to classical diagnostic methods, enabling repeated assessments and faster clinical decision-making. A promising strategy is to construct a multimarker biomarker panel that integrates proteomic, metabolomic, growth-factor, cytokine, and hormone indicators 25. However, a major limitation of current biomarker research is the incomplete characterization of the relationships between major depressive disorder (MDD) and other depressive conditions. Moreover, recent advances have identified numerous plasma biomarkers capable of quantifying growth factors, hormones, cytokines, and proteomic markers. Such multimarker panels may facilitate the modulation of dysregulated cytokine or growth-factor profiles, thereby enabling personalized interventions. A study by Xu et al. measured serum cytokine levels in 59 MDD patients and 61 healthy controls to identify diagnostic biomarkers and predict the response to antidepressant therapy 26. Significant baseline differences in several cytokines were observed between groups, suggesting that specific cytokine signatures may help discriminate patients with MDD from healthy subjects.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) as a potential biomarker

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are promising biomarkers for major depressive disorder (MDD). In the brain, miRNAs play essential roles in neural development, including growth, connectivity, experience-dependent neuronal adaptation, the regulation of synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmitter release. Disruption of miRNA function may therefore interfere with these processes and contribute to psychiatric disorders. Both brain function and treatment outcomes for MDD may be influenced by imbalances in miRNA activity; indeed, research supports a connection between miRNA and MDD. Liu et al. systematically investigated the participation of miRNAs in the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying MDD as well as their influence on response to therapy, thereby highlighting novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches 27. An initial examination of blood samples from patients diagnosed with depression and healthy controls identified five miRNAs with altered expression in depression. Mendes-Silva et al. performed high-throughput miRNA sequencing in late-life depression (LLD) 28. Compared with controls, hsa-miR-184 was significantly down-regulated in LLD patients. For functional examination, a Drosophila melanogaster model was used in which the knockout of the hsa-miR-184 orthologue caused reduced locomotor activity and memory impairments, particularly in older flies, mirroring depressive-like behaviors. These findings indicate that hsa-miR-184 may be involved in the pathophysiology of LLD and could provide a potential biomarker for diagnosing LLD. Fan et al. examined the miRNAs in PBMC samples as potential diagnostic biomarkers for MDD. In a sample of 81 patients with MDD, five miRNAs (miRNA-26b, miRNA-1972, miRNA-4485, miRNA-4498, and miRNA-4743) were found to be significantly up-regulated relative to 46 matched healthy controls based on Affymetrix microarray and RT-qPCR analysis 29. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis revealed a combined area under the curve of 0.636, demonstrating moderate diagnostic accuracy. Collectively, the findings suggest that aberrant miRNA expression in PBMCs represents a unique biomarker for the diagnostic evaluation of MDD.

Integrated diagnostic tools

A combinational diagnostic approach employing two or more neuroimaging modalities may improve diagnostic accuracy. Greicius et al. combined PET and fMRI to examine default-mode network (DMN) connectivity in major depressive disorder (MDD), thereby corroborating earlier PET findings of increased thalamic and subgenual cingulate activity 30. Their analysis further demonstrated that these seemingly isolated foci of hypermetabolism belong to a broader disrupted neural network. Accumulating evidence indicates that patients with MDD exhibit not only altered functional brain activity but also aberrant concentrations of several peripheral proteins compared with healthy controls. Consequently, a key question is whether such biological signals, when integrated with neuroimaging, can yield a precise and reliable diagnostic instrument for MDD. Chen et al. addressed this issue by integrating resting-state fMRI with a panel of serum protein biomarkers 31. Using linear discriminant analysis (LDA), they built diagnostic models showing that the combined multi-protein and neuroimaging feature set attained significantly higher accuracy than any single protein, isolated neuroimaging marker, or other one-dimensional combination. These findings underscore the potential of multidimensional, multimodal strategies to substantially enhance diagnostic precision in MDD.

Treatment strategies of MDD

Depression is a chronic condition that rarely remits spontaneously; if left untreated, it may persist for months or even years, disrupting daily functioning. Identifying an optimal treatment plan often requires time and iterative adjustment, yet this process is critical for successful disease management. Therapeutic selection is primarily determined by the subtype and severity of the depressive episode. In cases of mild depression, patient education, lifestyle modification, and psychotherapy alone may suffice. By contrast, moderate-to-severe episodes usually necessitate pharmacological treatment, often in combination with psychotherapy. Overall, therapeutic approaches are classified into two main categories: psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.

Psychotherapy

Major depressive disorder (MDD) responds positively to several psychotherapies rooted in different theoretical models and mechanisms. Robust evidence demonstrates that psychotherapy is effective for MDD, and no single approach is significantly more effective than any other. This observation has elicited two primary hypotheses to explain why distinct psychotherapies share common therapeutic benefits.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) assists individuals with MDD in identifying and challenging the negative thought patterns that perpetuate depression. Behavioral activation therapy (BAT) is a goal-oriented intervention that encourages depressed patients to increase engagement in rewarding activities, thereby enhancing pleasure and reducing depressive symptoms. BAT also addresses avoidance by detecting and targeting maladaptive avoidance patterns, enabling patients to break debilitating cycles and develop more adaptive coping strategies, resulting in improved mood and greater participation in life roles 32.

Owing to its exploratory nature, psychodynamic therapy (PyDT) allows patients to clarify links between past and present experiences and to recognize how their emotions and thoughts—often unconsciously—shape current functioning. Problem-solving therapy (PST) provides a systematic framework for confronting challenges, helping patients to generate novel solutions, identify implementation barriers, and plan and execute the necessary steps 33.

Interpersonal therapy (IPT) focuses on identifying interpersonal problems and addressing them with specific strategies 10. IPT is a time-limited, goal-oriented approach that helps patients recognize relationship and social patterns that may contribute to psychopathology, including unresolved conflicts, recent life transitions, and unsatisfying or unstable connections 34.

Pharmacotherapy

Despite considerable advances, the pharmacological management of depression continues to depend predominantly on agents discovered several decades ago that target monoaminergic neurotransmitter systems. These antidepressants increase synaptic concentrations of one or more monoamines by either inhibiting their re-uptake or preventing their enzymatic degradation. However, this mechanism represents only a partial explanation of the disorder's pathophysiology. Emerging evidence indicates that antidepressants also enhance neuroplasticity, leading to enduring structural and functional changes within the brain. Consequently, modulation of monoamines should be viewed merely as an initial step, underscoring the need for more sophisticated, multimodal therapeutic strategies that align with the heterogeneous clinical presentation of depression.

Mechanism of action

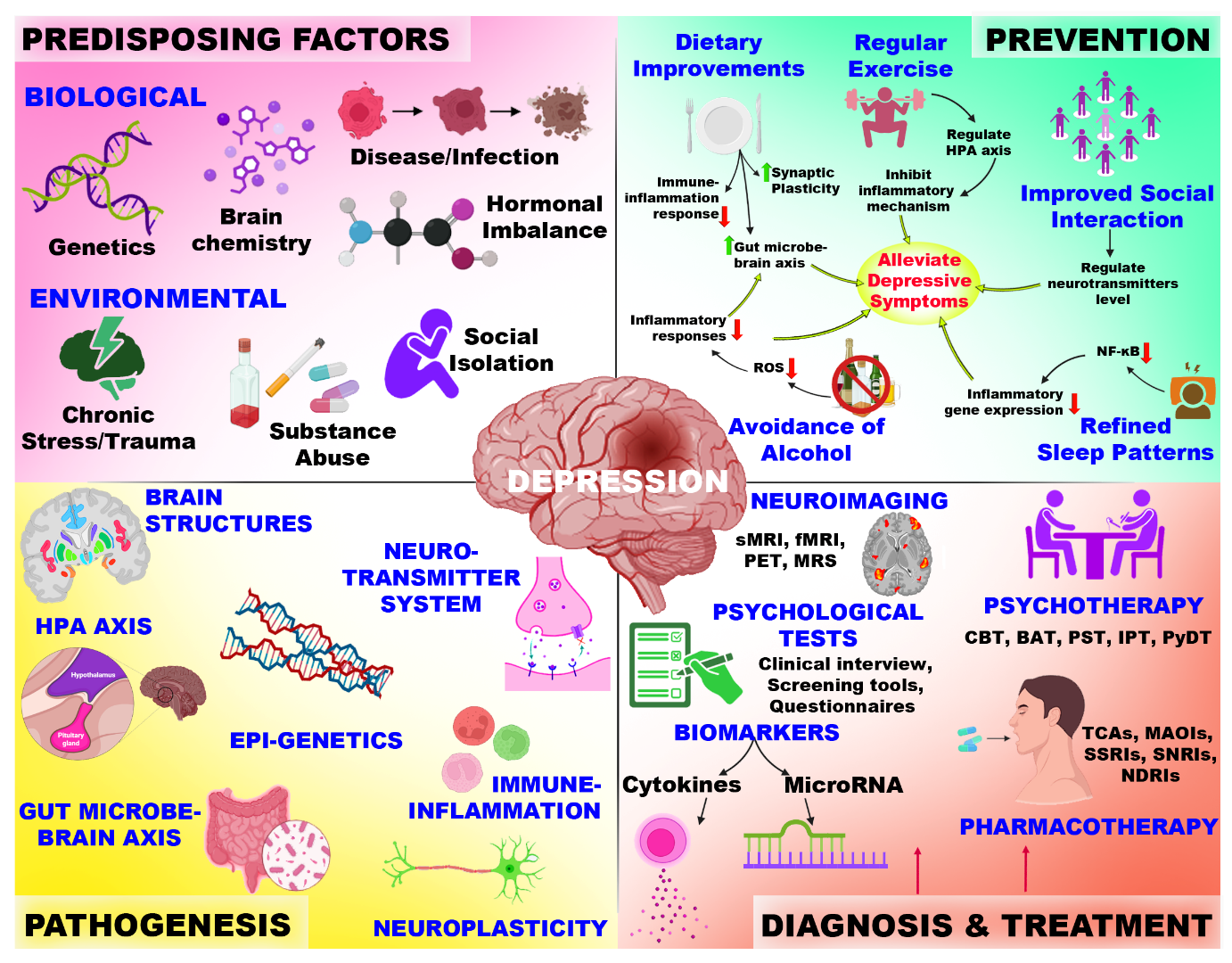

Monoaminergic neurotransmission constitutes a complex system encompassing the synthesis, vesicular release, uptake/reuptake, and enzymatic degradation of the monoamines serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, together with their associated transporters and receptors (Figure 2). This intricate network remains difficult to dissect when attempting to define its functional architecture and assess its druggability. Antidepressants that modulate monoaminergic tone induce adaptive neuronal responses, leading to changes in signal-transduction cascades, gene-expression profiles, synaptic plasticity, and hippocampal neurogenesis. Although the precise mechanisms underlying these alterations are not yet fully elucidated, they likely contribute to the therapeutic effect. The classical monoamine-based classification of antidepressants, despite its limitations, remains useful for predicting adverse-effect profiles and for elucidating drug mechanisms.

Mechanistic and key signaling pathways involved in the action of antidepressants at the synaptic core. The figure illustrates the influence of different categories of antidepressants on monoamine transmission by targeting various systems, including presynaptic transporters, metabolic enzymes, and postsynaptic receptors.

Classification of antidepressants

Antidepressant medications are widely prescribed and comprise several pharmacological classes, including tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), atypical antidepressants, and tetracyclic antidepressants. This classification reflects their mechanisms of action 35 (Figure 2). These agents primarily act within the central nervous system, altering the concentrations of the principal monoamine neurotransmitters—serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine (NE), and dopamine (DA). Although each class possesses a distinct pharmacodynamic profile, their shared therapeutic objective is to restore monoaminergic homeostasis and thereby mitigate depressive symptomatology.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs): MAOIs, once pioneering agents in antidepressant therapy, exert their effect by irreversibly inhibiting the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO), thereby increasing synaptic monoamine concentrations. However, their use is now currently restricted because of potentially severe food- and drug-related interactions, which generally relegates them to third- or fourth-line therapy in patients who do not respond to other antidepressants. Despite this, MAOIs retain robust efficacy in atypical depression, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, treatment-resistant depression, and bipolar depression, highlighting their value when other treatments fail 36.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): SSRIs are a class of agents routinely used to treat major depressive disorder and a range of other psychiatric conditions. They are considered first-line therapies owing to their well-established safety, efficacy and favorable tolerability profiles. According to the monoamine hypothesis, increasing synaptic serotonin levels may alleviate depressive symptoms 37. SSRIs achieve this by selectively inhibiting the serotonin transporter (SERT) on presynaptic neurons, thereby preventing serotonin reuptake. Consequently, serotonergic concentrations in the synaptic cleft rise, permitting prolonged stimulation of postsynaptic receptors. Unlike other antidepressant classes, SSRIs exhibit high selectivity for serotonin with negligible direct effects on dopamine or norepinephrine.

Serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) block presynaptic serotonin and norepinephrine transporters, increasing synaptic concentrations of both neurotransmitters and enhancing postsynaptic receptor activation. Individual agents within the class differ in transporter affinity; whereas duloxetine, venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine exhibit greater serotonergic than noradrenergic potency, milnacipran and levomilnacipran display the opposite profile, favoring norepinephrine inhibition. Despite their efficacy, SNRIs are associated with various adverse effects. Common reported events include nausea, xerostomia, dizziness, and headache 38.

Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs): Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs) are primarily employed for major depressive disorder (MDD) and as an aid to smoking cessation. They inhibit presynaptic reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine, neurotransmitters integral to mood, motivation, attention and reward pathways. This action elevates synaptic concentrations of these catecholamines, thereby enhancing neurotransmission and stabilizing mood. Bupropion is the prototype of this class and is approved for MDD and seasonal affective disorder (SAD). Marketed as Zyban for smoking cessation, bupropion attenuates nicotine craving and withdrawal symptoms. Mechanistically, bupropion preferentially inhibits dopamine reuptake and, to a lesser extent, norepinephrine, with negligible serotonergic activity; this pharmacological profile renders it suitable for patients seeking to avoid serotonin-mediated adverse effects. NDRIs are generally well tolerated, although adverse effects may still arise. Potential reactions include xerostomia, insomnia, headache and weight loss. Because of its stimulant-like properties, bupropion may increase energy and precipitate anxiety or agitation in some individuals. It can also elevate blood pressure and heart rate. Conversely, bupropion carries a low risk of sexual dysfunction, making it a valuable alternative for patients troubled by SSRI- or SNRI-induced sexual adverse effects 39. Clinicians should avoid bupropion in individuals with a history of seizures or eating disorders, as the drug lowers the seizure threshold. Accordingly, seizure risk increases with higher doses and in predisposed patients.

Concerns in Pharmacotherapy: The Role of Antidepressants

The array of antidepressants available today is extensive; however, their clinical use is fraught with challenges. Notably, most antidepressants require prolonged administration to achieve therapeutic effects, with intranasal esketamine representing a noteworthy exception. Furthermore, their use is often accompanied by adverse effects, including weight gain, sexual dysfunction, dizziness, headache, anxiety, psychosis, and cognitive impairment40. Patients with comorbidities face significant challenges when using antidepressants due to substantial contraindications related to potential drug–drug interactions. Co-prescription of antidepressants with other medications can be hazardous, particularly in complex polypharmacy regimens and during extended treatment periods41. Research highlights the concerns surrounding drug–drug interactions, emphasizing the need for cautious prescribing practices and thorough monitoring. The concurrent use of antidepressants and cardiac medications poses significant pharmacokinetic risks due to shared hepatic cytochrome P450 pathways42.

Despite the availability of these therapies, limitations and challenges persist with current depression treatments, highlighting the need for novel, more effective options43. Physiological barriers constitute another obstacle for drug delivery. The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is a key interface between the bloodstream and the brain, yet it presents a major hurdle for pharmacotherapy in neurological diseases. Comprised of tightly arranged endothelial cells, astrocytes, and pericytes, the BBB regulates molecular transit by size, charge, and lipophilicity. Numerous neurotherapeutic agents fail to traverse this barrier, thereby narrowing their therapeutic window. Molecular size, lipophilicity, and electrostatic charge, together with efflux transporters such as P-glycoprotein, are primary impediments. Specifically, tight junctions hinder the passage of large molecules, the lipid bilayer restricts hydrophilic drugs, and the negatively charged endothelial surface repels cationic compounds, collectively impeding effective drug delivery to the brain.

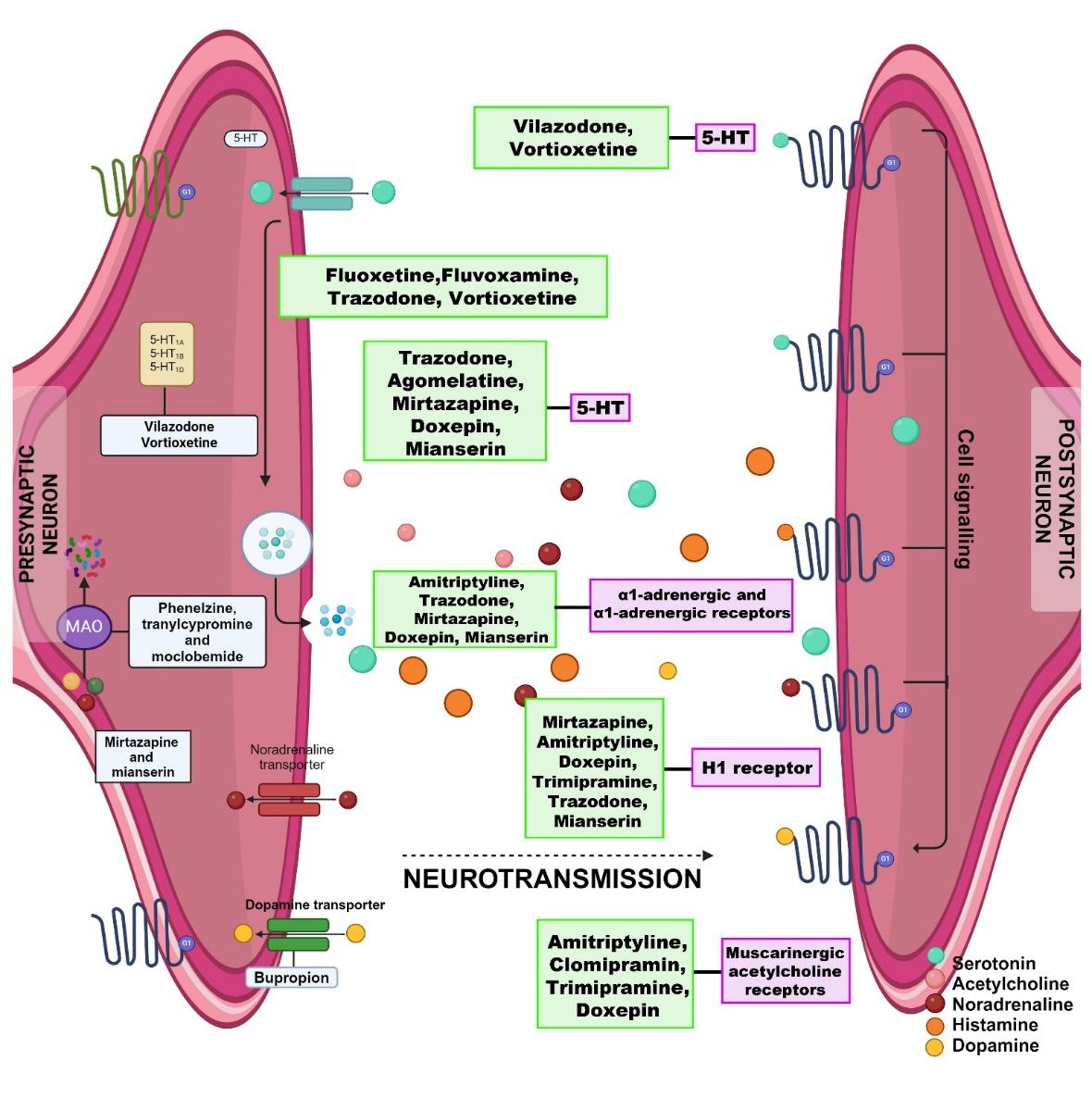

Potential role of nanomedicine

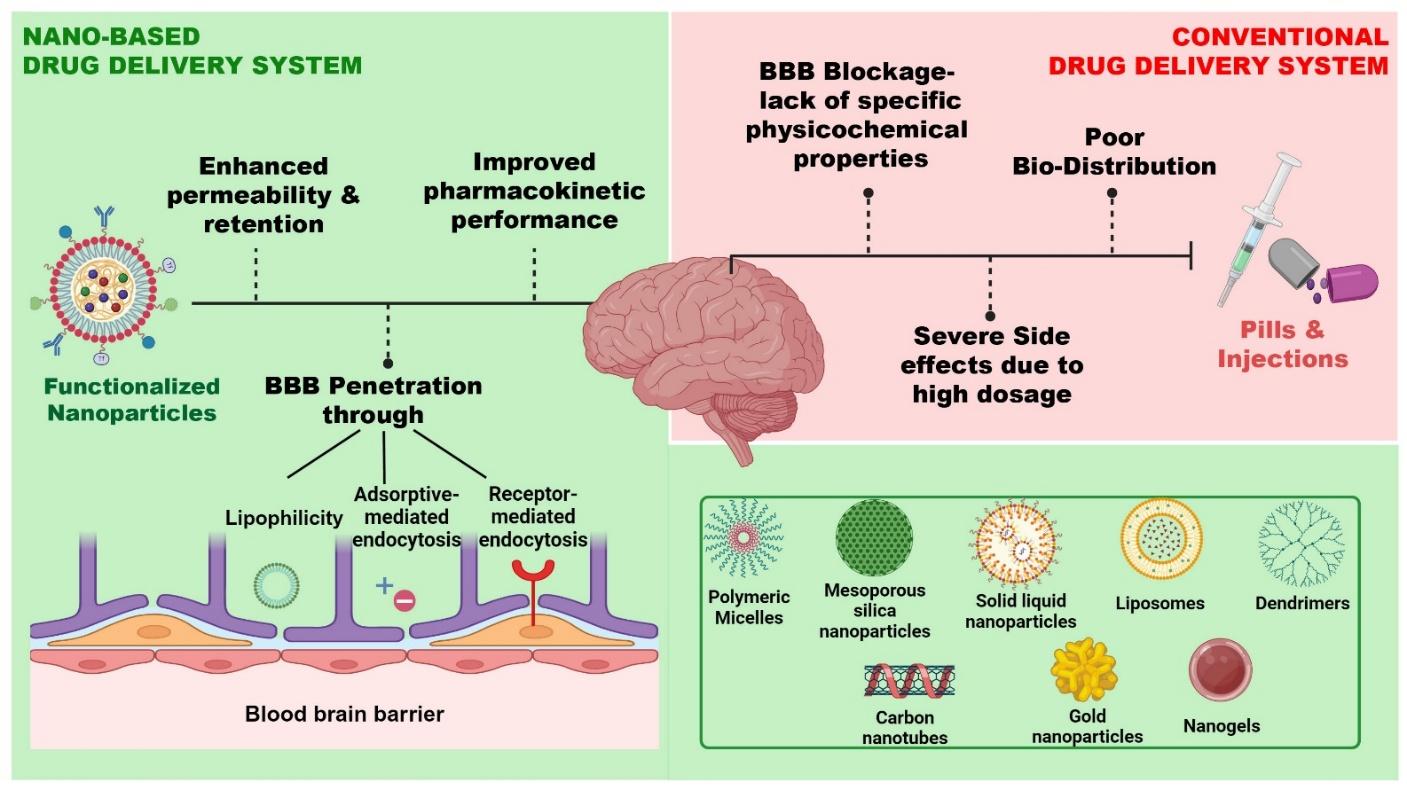

Nanotechnology has evolved over the past few decades from a primarily theoretical concept into a mature, wide-ranging discipline, with nanomedicine emerging as one of its most pivotal applications. A multidisciplinary strategy facilitates the rational design of optimized therapeutics and diagnostic tools, thereby reshaping the healthcare landscape 44. At the nanoscale, materials exhibit physicochemical characteristics that differ markedly from their bulk counterparts; these properties can be finely tuned by modulating particle size and morphology. Consequently, nanoparticles can be engineered into diverse architectures—including nanoflowers, nanostars, nanoboxes, nanospheres, nanochains, and nanorods—to suit specific biomedical purposes 45,46. Broadly, the field encompasses both nanoparticles and nanodevices, the latter comprising specialized particles capable of interacting with cells and tissues in the circulation to monitor drug kinetics, modulate biological pathways, and serve as imaging contrast agents 47. By comparison, nanorobotics—encompassing the design, fabrication, programming, and control of autonomous nanoscale robots—remains largely conceptual because of unresolved safety and regulatory issues. Nonetheless, research momentum has increased substantially, and three principal nanorobot configurations (helices, nanorods, and DNA-based robots) are presently being investigated in vitro for targeted payload delivery 48. The incorporation of nanotechnology has revolutionized pharmacology, oncology, tissue engineering, and biosensing, and has opened novel avenues for interrogating the central nervous system (CNS) (Figure 3). In CNS applications, nanoparticles can traverse biological barriers such as the blood–brain barrier, deliver drugs with high spatial precision, and reduce off-target toxicity by lowering the required dose. Accordingly, nanotechnology is poised to enhance the diagnosis and management of psychiatric disorders and to advance the broader paradigm of precision medicine. Figure 3 schematically contrasts conventional and nano-enabled drug-delivery systems, summarizes the advantages of nanoscale carriers, catalogues representative nanoparticle vehicles, and outlines the mechanisms by which they penetrate the blood–brain barrier.

Comparative schematic representation highlighting the conventional vs. the nanoparticle drug delivery system for CNS delivery. The figure depicts the limitations of the conventional delivery systems, including poor bio-distribution and severe side effects. It also highlights the advantages of nano-based delivery systems, focusing on enhanced BBB penetration.

Advantages of nanomedicine in drug delivery

Nanostructured delivery carriers confer two principal advantages related to drug stability. First, nanoparticles protect encapsulated agents from in-vivo degradation, thereby preserving their potency and therapeutic efficacy. Drug entrapment within nanocarriers prevents premature enzymatic or physicochemical breakdown. Second, these systems can bypass the first-pass effect—a rapid hepatic metabolism that markedly reduces the bioavailability of especially water-insoluble compounds. By avoiding this barrier, nanocarriers facilitate sufficient delivery of the active substance to the intended tissues 49. In addition, the release kinetics of the payload can be precisely modulated by tailoring the carrier composition, a feature that mitigates untargeted, premature off-site release and consequently diminishes systemic toxicity while enhancing therapeutic outcomes.

The primary advantage of nanoscale drug-delivery systems is their capacity for precise targeting, enabling site-specific drug deposition. Such smart delivery is made possible by nanoparticles due to their diminutive size, amenability to surface functionalization, and high drug-loading capability. Through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, nanoparticles preferentially accumulate within tumours or inflamed tissues. In addition, conjugated surface ligands mediate receptor-specific recognition of target cells, while stimuli-responsive matrices trigger cargo release in defined microenvironments (e.g., pH, enzymatic activity, temperature). Collectively, these features increase therapeutic efficacy and minimize systemic exposure and off-target toxicity 50,51,52. By concentrating the pharmacological payload at the site of action, nanomaterial-based delivery both augments therapeutic outcomes and diminishes adverse events, an approach that continues to attract intense investigative and clinical interest. For accurate cellular targeting, researchers engineer surface modifications with high-affinity ligands that promote selective accumulation and uptake by diseased cells. This “active targeting” strategy entails decorating the nanovehicle with moieties capable of binding specific receptors overexpressed on pathological cells, thereby ensuring localized drug distribution and optimal therapeutic benefit 53. Furthermore, particle size reduction to the nanoscale dramatically enhances apparent solubility owing to the increased surface-area-to-volume ratio. The expanded interfacial area facilitates greater solvent access, accelerating dissolution kinetics and, consequently, improving bioavailability.

The biocompatibility of nanoparticles is a crucial advantage in drug delivery, ensuring minimal toxicity and adverse reactions, thereby enhancing patient safety, and improving the efficacy of therapeutic agents. Biocompatible nanoparticles interact favorably with biological systems, do not trigger inflammatory responses, and maintain structural integrity in biological environments, facilitating targeted drug delivery and enabling repeated administration without adverse effects. Key factors influencing nanoparticle biocompatibility include material composition, surface chemistry, size, shape, charge, hydrophobicity, and the degree of functionalization or surface modification 54. Their nanoscale dimensions enable nanoparticles to evade the reticuloendothelial system (RES), which filters foreign substances from the bloodstream. This evasion allows nanoparticles to remain in circulation for extended periods, thereby increasing drug exposure and potentially improving therapeutic efficacy. Appropriate surface modifications further enhance stealth properties, prolong circulation time, and facilitate targeted delivery. By dodging immune detection, nanoparticles maintain bioavailability, ensuring that therapeutic agents reach the intended tissues. Rationally designed nanoparticles with optimized surface properties can revolutionize drug delivery, offering improved treatment outcomes and patient benefit. This strategic design enables nanoparticles to outsmart the body’s defense mechanisms, maximizing therapeutic potential. As noted above, nanoparticles enable precise targeting of specific cells or tissues, delivering drugs directly to their intended sites of action; this approach minimizes exposure to healthy tissues and organs, thereby reducing the risk of harm. As a result, lower doses are often required, leading to fewer side effects and improved patient outcomes. By combining targeted delivery, improved bioavailability, and reduced dosing, nanoparticles significantly minimize systemic toxicity. This synergistic effect enhances the safety and efficacy of drug delivery, revolutionizing treatment outcomes.

A study by Haque et al. formulated and evaluated venlafaxine-loaded alginate nanoparticles (VLF-AG-NPs) for intranasal brain delivery in the treatment of depression. The nanoparticles were characterized with respect to their physicochemical properties 55. Pharmacodynamic effects were assessed in albino Wistar rats via the forced-swim test (FST) and locomotor activity assay. Intranasal administration of VLF-AG-NPs significantly improved behavioral outcomes—increased swimming and climbing and reduced immobility—compared with free VLF solution and oral VLF tablets; locomotor performance was likewise enhanced. Direct brain targeting was confirmed by confocal laser-scanning microscopy of Rhodamine-123-loaded alginate nanoparticles 55. These experiments demonstrated efficient nanoparticle distribution to the brain after intranasal dosing. Pharmacokinetic analysis showed that brain-to-blood VLF ratios were markedly higher after intranasal VLF-AG-NPs than after intranasal or intravenous VLF solution, particularly at the 30-min time point, indicating augmented direct brain transport. Overall, intranasal VLF-AG-NPs achieved greater cerebral uptake, superior pharmacodynamic activity, and improved targeting efficiency, suggesting alginate-based nanoformulation as a promising strategy for depression therapy 55.

In a separate investigation, Gao et al. developed docetaxel-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (DSNs) and rigorously assessed their preclinical safety 56. DSNs produced no hypersensitivity or vascular irritation at clinically relevant concentrations. In acute toxicity studies, the maximum tolerated dose in mice reached 400 mg kg⁻¹, markedly exceeding the lethal dose of Taxotere (LD₅₀ = 149.3 mg kg⁻¹). In a 28-day repeated-dose study in beagle dogs, Taxotere (1 mg kg⁻¹) induced flushing, vocalization, and salivation, whereas DSNs at four-fold higher doses elicited no abnormal responses. At equivalent dosing, DSNs caused only minor reductions in weight gain and significantly less hematotoxicity, cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and myelosuppression than Taxotere 56, underscoring their superior safety and handling profile.

Cayero-Otero et al. fabricated venlafaxine-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles via a double-emulsion solvent-evaporation method 57. The formulation achieved 55–65 % entrapment efficiency, 190–210 nm particle diameter, a polydispersity index < 0.2, and a zeta potential of ≈ –20 mV. In vitro exposure of human olfactory neuroepithelial cells preserved > 90 % viability across all concentrations, exhibited no cytotoxicity, and demonstrated clear nanoparticle internalization. In vivo, seven-day intranasal delivery ameliorated depressive-like behavior in rodents, as shown by open-field, sucrose-preference, and tail-suspension tests, with significantly stronger antidepressant-like effects than free venlafaxine 57. These findings indicate that this nanoparticle platform is a safe and effective vehicle for nose-to-brain venlafaxine delivery.

Nano-mediated approaches for depression

Nano-mediated approaches exploit nanoparticles to create innovative therapeutics, diagnostic modalities, and drug-delivery platforms for neurological and psychiatric disorders, thereby conferring distinct advantages. Because of their diminutive dimensions, nanoparticles can traverse biological barriers such as the blood-brain barrier (BBB), rendering them well-suited for targeted CNS delivery. Their high surface-to-volume ratio further facilitates efficient drug loading and transport. Conventional antipsychotic and antidepressant agents frequently encounter the BBB, which limits central penetration, diminishes efficacy, and increases systemic adverse effects 58. The nanoscale dimensions of these carriers permit circumvention of such barriers, potentially transforming psychiatric pharmacotherapy. This integration has given rise to the field of “nanopsychiatry,” underscoring its emerging clinical relevance. Nanomaterials already play a crucial role in experimental neurophysiology, allowing precise interrogation of normal and pathological neural circuits. In addition, drug-loaded nanocarriers can be engineered to modulate specific signaling pathways as agonists or antagonists, while simultaneously enabling real-time monitoring of associated physiological processes. Currently approved antidepressants are hampered by limited BBB penetration, dose-related toxicity, and suboptimal bioavailability. Consequently, nearly one-third of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) exhibit inadequate therapeutic response. Several compounds are also vulnerable to gastrointestinal enzymatic degradation, further curtailing their efficacy. Nano-enabled delivery systems offer a feasible strategy to overcome these limitations. Diverse nanocarriers are under investigation for BBB translocation, capitalising on their physicochemical attributes. Such platforms enhance solubility and stability, provide stimulus-responsive or sustained release, and decrease dosing frequency as well as off-target toxicity. Moreover, nanocarriers shield encapsulated agents from enzymatic degradation, thereby augmenting antidepressant efficacy. A recent triple-blind randomised controlled trial by Noormohammadi et al. evaluated nano-selenium supplementation as an adjunct therapy for MDD. The investigators examined effects on the JAK/STAT pathway; participants received nano-selenium 55 µg day⁻¹ or placebo in conjunction with standard antidepressants. Nano-selenium produced a numerically greater down-regulation of JAK2 and STAT3 expression, although inter-group differences did not reach statistical significance. This trial constitutes one of the earliest first-in-human evaluations of a nanoparticle-based intervention for depression, yielding preliminary evidence of safety and biological activity 59.

Nano-based drug delivery carriers to deliver across the BBB

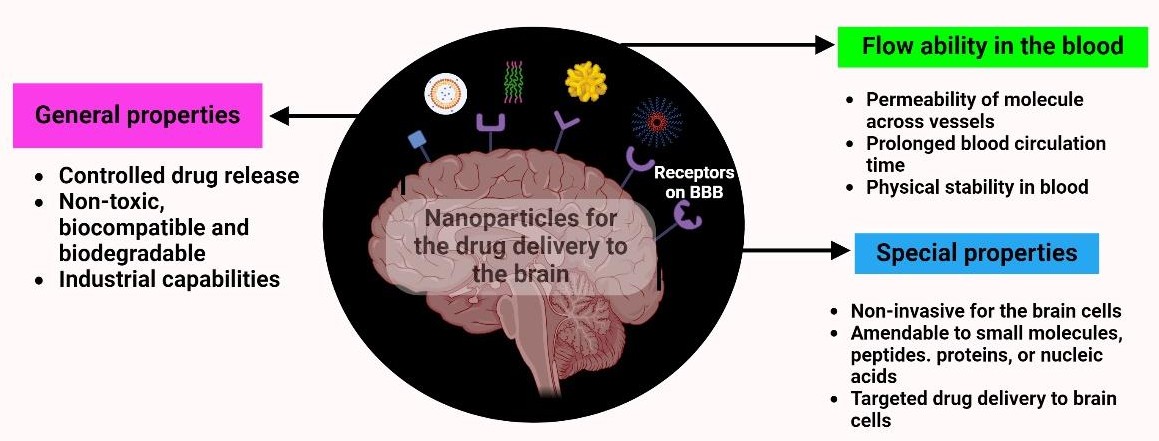

Nanotechnology-based drug-delivery carriers are synthetic constructs characterized by unique physicochemical attributes that revolutionize pharmacotherapy by improving bioavailability, shielding therapeutic agents from enzymatic degradation, and facilitating sustained systemic circulation (Figure 4). By fine-tuning their composition and architecture, these platforms enhance drug stability and allow controlled release kinetics, thereby prolonging the antidepressant effect and decreasing dosing frequency. Moreover, nanocarriers can be engineered for site-specific delivery through the incorporation of target-directing surface ligands, enabling the preferential accumulation of antidepressants in pathological brain regions, maximizing therapeutic efficacy while limiting off-target toxicities.

It presents the key physicochemical and functional advantages of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems. This summarizes general properties of nano-based systems such as controlled drug release, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and scalability.

Types of nanocarriers for antidepressants

A wide variety of nanoparticles are under active investigation as nanocarriers for drug delivery, particularly for crossing the blood–brain barrier (BBB). These platforms encompass lipid-based nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, metallic nanoparticles, ceramic nanoparticles, quantum dots, dendrimers, nanocapsules and nanoemulsions, each possessing distinct physicochemical properties that can be leveraged for targeted brain delivery. Although most nanoparticles do not readily breach the BBB, carriers fabricated from biodegradable polymers display superior permeability owing to their colloidal stability. These polymers can evade the reticuloendothelial system (RES), thereby extending systemic circulation and allowing the encapsulated drug to reach its site of action. Furthermore, biodegradable polymer-based nanocarriers exhibit minimal toxicity, making them a promising platform for the development of safe and effective drug-delivery systems.

Compilation of nanocarriers used to encapsulate the commercial antidepressants

| Nanocarrier | Synthesis method | Cargo | Test model | Key outcomes | Size/PDI/Charge | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nano-transethosome | Hot method | Agomelatine | Swiss albino mice | Higher skin permeation, prolonged release, and improved behavior | 156.8 nm | - | |

| Liposomes | Thin lipid film hydration method | Vortioxetine hydrobromide | Mice model | Stability, no acute toxicity, and improved antidepressant effect | 176.74 nm ± 2.43 | 2.5 mg/kg to 10 mg/kg | |

| Polymer- Poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid- | Nanoprecipitation method | Agomelatine | Ex vivo study- goat nasal mucosa and in vivo- Rats | Sustained release, high permeability, no nasal toxicity | <200 nm/ -22.7 mV | - | |

| Bio-nano gels- biopolymer | - | Escitalopram | Ex vivo study- goat skin | Higher stability | - | - | |

| Nanocapsules with a biodegradable polymeric shell | Nanoprecipitation technique | Trazodone hydrochloride | Mice model | Controlled release and enhanced antidepressant efficacy | 172.4 ± 2.2 nm/ PDI- <0.3/ ± 20 mV | 5 mg/kg | |

| Solid Lipid Nanoparticles | Hot homogenization method | Sertraline hydrochloride | Rat model | Reduced immobility duration | - | 20 and 50 mg/kg | |

| Solid lipid nanoparticles | Nano-template engineering technology | Duloxetine | In vivo study | Reduced depressive behavior, suppressed the inflammatory markers | 114.5 nm/PDI-0.29/-18.2 mV | - | |

| Nanostructured lipid carriers | Melt Emulsification-Ultrasonication process | Venlafaxine | Ex vivo- sheep nasal mucosa | Prolonged release with higher permeability. | 155 and 293 nm/ 213±4.3/ -35 mV | - |

Lipid-based nanocarrier systems

Lipid-based nanocarrier systems have emerged as a promising platform for delivering therapeutic agents to the central nervous system (CNS) by circumventing the restrictive blood–brain barrier (BBB). By optimizing the physicochemical composition and surface properties of these nanocarriers, investigators have successfully enhanced trans-BBB permeability, thereby enabling efficient delivery to brain parenchyma. This advancement has important implications for the treatment of numerous neurological disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD), Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis. Collectively, lipid-based nanocarriers may provide a viable solution to the challenges inherent in CNS drug delivery, thereby paving the way for more effective therapies and improved patient outcomes.

Liposomes: Liposomes are versatile, spherical vesicular carriers typically composed of phospholipid bilayers 68. Their bilayer, with hydrophilic headgroups oriented toward the inner and outer aqueous phases and hydrophobic acyl chains sequestered within the membrane, permits the encapsulation of hydrophilic drugs within the aqueous core as well as the incorporation of lipophilic molecules into the lipid bilayer. This structural flexibility enables liposomes to deliver a broad spectrum of therapeutic agents effectively 69. Consequently, liposomes have been employed in the treatment of a variety of diseases, including malaria and several cancers, by virtue of their capacity for targeted delivery, controlled release, reduced systemic toxicity, and enhanced in-vivo stability.

Khute and Jangde, using an in-silico approach, designed a venlafaxine-loaded liposomal formulation that exhibited high entrapment efficiency (~90 %) and a mean particle diameter of approximately 190 nm 70. In vitro release studies demonstrated superior drug release kinetics relative to the free drug. These data suggest that liposomal venlafaxine constitutes a promising nose-to-brain delivery platform capable of improving pharmaceutical performance, therapeutic efficacy, and bioavailability in the management of depression. Furthermore, the intranasal administration route appeared robust and may translate into enhanced clinical outcomes.

Chawla formulated and characterized sertraline hydrochloride-loaded liposomes via the thin-film hydration method 71. The resultant vesicles exhibited controlled drug release and enhanced antidepressant-like activity. In a stress-induced rat model, liposomal sertraline significantly improved behavioral parameters—increasing swimming and decreasing immobility and struggling durations—relative to a commercial sertraline preparation. These observations indicate that liposomal sertraline represents a promising strategy for the treatment of depression.

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs): SLNs are unilamellar, discoidal-to-spherical particles composed of solid lipids stabilized by surfactants. Drugs can be embedded within the lipid core or adsorbed onto the particle surface, thereby enabling targeted delivery and improved tissue penetration. SLNs afford several benefits, including enhanced pharmacological efficacy, reduced hepatic clearance, and straightforward encapsulation of amphiphilic drugs. They have been extensively investigated as carriers in vaccines, anticancer therapy, antimicrobial treatment, and gene delivery, confirming their potential as an effective and efficient drug-delivery system. Rana et al. evaluated duloxetine-loaded SLNs with the aim of maximizing antidepressant activity in a lipopolysaccharide-induced rat model of depression 66. Particles were produced via nano-template engineering. Behavioral assays (forced-swim and tail-suspension tests) demonstrated superior antidepressant effects, while ELISA indicated increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) concentrations in brain and plasma. Immunohistochemistry further revealed attenuated inflammation, supporting SLNs as promising carriers for brain-targeted delivery of antidepressant drugs.

Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs): To overcome these limitations, second-generation NLCs were developed. NLCs incorporate a mixture of solid and liquid lipids, offering greater drug loading and improved in vitro performance. Compared with SLNs, NLCs provide superior stability, more precise release kinetics, and higher drug loads, thereby delivering an attractive system for various therapeutic purposes. Gul et al. formulated agomelatine-loaded NLCs to enhance the drug’s therapeutic effectiveness 72. The formulation exhibited favorable physicochemical properties, sustained in vitro release, and superior in vivo antidepressant efficacy in mice. These findings confirm that NLCs represent a potential nanocarrier for effective brain delivery of antidepressants.

Polymer-based nanocarriers

Continuous efforts are under way to combine psychiatric drugs with polymeric nanoparticles to overcome major barriers in antipsychotic therapy 85,86. The primary goals include enhancing bioavailability, increasing therapeutic efficacy, and diminishing adverse effects associated with long-term antipsychotic use, particularly extrapyramidal symptoms. Ultimately, researchers aim to exploit polymeric nanoparticles to create more effective psychiatric formulations that minimize side-effects and improve patients’ quality of life.

Polymeric micelles are self-assembled nanostructures formed by amphiphilic block copolymers when their concentration exceeds the critical micellar concentration, yielding thermodynamically stable particles. They possess a hydrophobic core and hydrophilic shell, enabling controlled release of poorly soluble drugs and enhanced bioavailability. Their small diameter (10–200 nm), structural stability, and low toxicity render them well-suited for drug delivery. The hydrophobic core sequesters the drug, acting as a sustained-release reservoir, whereas the hydrophilic shell mitigates serum protein adsorption and complement activation, thereby limiting premature drug loss. Hydrophilic moieties such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) are commonly incorporated to evade the reticuloendothelial system, prolong circulation, and improve stability. Inherent to PEG is its capacity to penetrate mucus, facilitating trans-mucosal transport and further justifying its inclusion in micellar designs 73. El-Helaly et al. encapsulated mirtazapine within polymeric micelles, resulting in improved solubility and enhanced bioavailability 74. The formulation exhibited satisfactory stability, indicating that polymeric micelles can serve as an efficient carrier system.

Dendrimers: Dendritic macromolecules, characterized by their unique spherical, highly branched architecture and numerous active sites, offer a versatile platform for drug delivery. These hyperbranched structures can encapsulate drugs within their interior or attach them to their surface through hydrophobic interactions or covalent bonding, depending on the physicochemical stability of the payload. The unique structure and functional surface groups of dendrimers provide several key benefits, including improved biocompatibility, prolonged systemic circulation, and precise targeting, making them promising tools for advanced therapeutic delivery. Consequently, efficient and controlled drug release can be achieved, minimizing potential side effects and improving therapeutic efficacy. Fard et al. synthesized polyester dendrimers functionalized with graphene oxide and loaded with venlafaxine 75. The formulation displayed a sustained-release profile and showed enhanced biocompatibility after conjugation with 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid. In cytotoxicity assays, the system maintained high cell viability. Overall, dendrimers represent biocompatible and biodegradable nanocarriers capable of transporting antidepressants.

Chitosan: Chitosan, a naturally derived biopolymer, exhibits exceptional biocompatibility and biodegradability, rendering it suitable for biomedical applications, particularly within the central nervous system (CNS). Its degradation products are non-toxic, non-accumulating, and non-antigenic, ensuring safe elimination from the body. These favorable properties enhance chitosan’s ability to traverse the blood–brain barrier (BBB), facilitating targeted delivery of therapeutic agents to the CNS. Accordingly, chitosan has emerged as a promising vector for CNS-oriented drug-delivery systems. Saeedi et al. developed Tween 80-coated chitosan nanoparticles to enhance the brain distribution of venlafaxine 76. The nanoparticles were non-toxic and demonstrated improved biodistribution in mice. Relative to uncoated nanoparticles or an aqueous venlafaxine solution, Tween 80-coated nanoparticles increased venlafaxine concentrations in brain tissue within 1 h after administration, indicating enhanced cerebral uptake. These findings suggest that surface-modified, venlafaxine-loaded chitosan nanoparticles may improve brain delivery and therapeutic efficacy, offering a promising strategy for the management of generalized anxiety disorder. Additional nanocarrier systems that efficiently encapsulate active agents and yield improved outcomes are summarized in

Potential nanocarriers used to encapsulate the active agents that act as an antidepressant

| Nanocarrier | Synthesis method | Cargo | Surface Functionalization | Test model | Key outcomes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid-based, polymer-based, and polymer/lipid hybrid | - | Curcumin | - | Sprague-Dawley male rats | increased weight, improved sucrose consumption, and restored normal behavior | |

| Nanogels | Reverse microemulsion method | Icariin | NGSTH- for thermosensitivity | Mice model | Increased weight, improved sucrose consumption, and normalized testosterone levels | |

| Quercetin-based alginate nanogels | - | BDNF | Poloxamer- for thermosensitivity | Sprague-Dawley rats | Improved bioavailability with slow and sustained release, and reversed depressive behavior | |

| Cyclic RGD liposomes | - | Edaravone | - | Rat model | Improved behavioral activity and normalized cytokine levels | |

| Liposomes | - | Oxytocin | N-Acetyl Pro-Gly-Pro (PGP) peptides | Rat model | Increased neutrophil levels, bioavailability, and improved behavioral measurements. | |

| Liposomes | - | Amphotericin B | - | Mice model | Reversed depression behavior and increased sucrose preference test scores | |

| Liposome | - | Nimodipine | - | Mice model | Decreased MAOB activity and reduced immobility | |

| Chitosan nanoparticles | Ionic gelation method | Tramadol HCl | Pluronic and HPMC-based mucoadhesive thermo-reversible gel | In vitro study | Increased locomotor activity, body weight, and showed significant alterations in biochemical parameters. | |

| Nanostructured lipid carriers | Nanotemplate engineering technique | Curcumin | Poloxamer 188, Tween 80, and Span 80- as stabilizers | Rat model | Exhibited biphasic release, with an initial burst followed by sustained release, demonstrated a neuroprotective effect. | |

| Hydroxylpropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD) | - | Berberine | Poloxamer- as thermosensitivizer | Rat model | High therapeutic efficiency at a low dose and restored mitochondrial dysfunction | |

| Solid lipid nanoparticles | - | Curcumin | - | Mice model | Higher permeability with improved bioavailability | |

| Solid lipid nanoparticles | Dexanabinol and Curcumin | Increased mRNA and protein expression with enhanced locomotion profile |

Surfactants based nanocarriers

Nanoparticles possess an exceptionally high surface-to-volume ratio that confers distinct physicochemical advantages relative to bulk materials. The functional performance of these nanostructures can be further optimized through the adsorption of surfactants—amphiphilic molecules that lower interfacial tension—thereby improving their colloidal stability and drug-loading capacity. Consequently, surfactant-modified nanoparticles constitute the foundation of next-generation drug-delivery platforms, providing improved pharmacokinetics, targeting accuracy, and bioavailability.

Niosomes are non-ionic surfactant-based vesicles that have gained attention as carriers for central nervous system (CNS) therapeutics. Their closed bilayer architecture allows simultaneous entrapment of hydrophilic solutes in the aqueous core and lipophilic compounds within the bilayer, safeguarding the payload from enzymatic degradation and enhancing systemic bioavailability. Reported advantages include increased permeability across the blood–brain barrier (BBB), site-specific delivery within the CNS, superior drug solubility and physicochemical stability, diminished off-target toxicity, and sustained release kinetics 89.

Bilosomes—vesicular systems composed of bile salts and phospholipids—also demonstrate promise for CNS drug delivery. The incorporation of bile salts confers membrane fluidity and resistance to intestinal bile-salt-induced lysis, enabling efficient trans-BBB transport of both hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs. In preclinical studies, bilosomes improved drug solubility, stability, and bioavailability while minimizing systemic adverse effects. Post-synthetic surface functionalization with targeting ligands further facilitates region-specific delivery within the CNS 90. Bilosomes have been investigated for the transport of neuroprotective agents, chemotherapeutics, and antivirals aimed at major depressive disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, brain tumours, and other neurological pathologies. Owing to their intrinsic biocompatibility and biodegradability, bilosomes represent a versatile platform for CNS-directed nanotherapeutics. A comparative summary of recent vesicle-based nanocarriers (bilosomes and niosomes) and their respective advantages is provided in

Development of Niosomal and Bilosomal nanocarriers for encapsulating antidepressants

| Nanocarrier | Synthesis | Reactants | Functionalization | Antidepressants | Test model | Key outcomes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Niosomes | Ether injection method | Span 40, span 60, span 80 | - | Setraline hydrochloride | In vitro | Promising transdermal delivery | |

| Thin film hydration | Span 60 | - | Desvenlafaxine succinate | In vitro | High stability | ||

| Ether injection method | Span 80 | - | Venlafaxine hydrochloride | - | High bioavailability and sustained release | ||

| Bilosomes | Thin film hydration | Span 60, sodium deoxycholate | - | Sertraline hydrochloride | In vivo | High oral bioavailability and reduced gastric upset. | |

| Thin film hydration | Span 60, and sodium deoxycholate | - | Desvenlafaxine succinate | In vivo | Increasing bioavailability and effectiveness | ||

| Thin film hydration | Sodium deoxycholate | Hyaluronic acid | Venlafaxine | In vitro | High bioavailability | ||

| Ethanol injection technique | Sodium deoxycholate, sodium cholate, sodium taurocholate | Hyaluronic acid | Agomelatine | In vivo | Higher elasticity, improved ocular delivery, and bioavailability |

Metallic nanocarriers

Metallic nanoparticles enhance the therapeutic efficacy of drugs by facilitating targeted delivery and mitigating multidrug resistance. They are widely employed as vehicles for delivering various therapeutic agents, including antibodies, nucleic acids, and chemotherapeutic drugs. Metallic nanocarriers, such as gold, silver, iron oxide, and zinc oxide nanoparticles, have emerged as versatile platforms for enhancing drug delivery. By increasing solubility, prolonging systemic circulation, and reducing renal clearance, these nanocarriers provide a promising approach to optimizing pharmacological efficacy. Although the nanocarrier systems discussed—including solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs), niosomes, and polymeric formulations—have demonstrated considerable promise for antidepressant delivery, identifying a universally superior vehicle remains challenging. The performance of each system depends primarily on the physicochemical properties of the encapsulated drug, which govern its encapsulation efficiency, stability, and release kinetics. In general, lipid-based carriers afford prolonged release and enhance bioavailability, whereas polymeric systems offer greater tunability for targeted delivery. Nevertheless, these advantages are context-dependent, and the optimal nanocarrier must ultimately be selected empirically through iterative optimization tailored to the specific drug and therapeutic objective.

Route of nanocarrier administration

Several administration routes have been systematically explored for the deployment of nanocarriers in depression management, and the selected route profoundly influences absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination (ADME). Oral delivery remains the predominant option because it is non-invasive, convenient, and cost-effective; however, extensive pre-systemic metabolism in the gastrointestinal mucosa and liver markedly diminishes bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy. In addition, the blood–brain barrier (BBB) poses a formidable obstacle to central nervous system (CNS) exposure. To address these limitations, researchers have engineered next-generation oral nanocarriers that improve stability, enhance intestinal uptake, and increase neuroavailability, thereby potentially augmenting clinical outcomes.

Parenteral administration bypasses first-pass metabolism and enables rapid systemic exposure. Intravenous (IV) injection provides immediate access to the circulation and an accelerated onset of action, whereas intramuscular (IM) injection supports slower, sustained absorption 98. Although both routes permit subsequent BBB penetration, distribution remains largely non-selective and may precipitate peripheral adverse effects; current investigations are focusing on surface functionalization and ligand-mediated targeting to optimize CNS delivery.

Intranasal administration offers a minimally invasive alternative that combines rapid systemic absorption with direct nose-to-brain transport via the olfactory and trigeminal pathways. This strategy circumvents gastrointestinal and hepatic metabolism as well as the BBB, leading to a faster pharmacodynamic response, higher brain bioavailability, and fewer systemic interactions 99.

Animal model for neurological studies

Animal models remain indispensable tools in contemporary neurological research, furnishing critical insights into the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of a wide spectrum of nervous-system disorders. By recreating complex biological processes under controlled laboratory conditions, investigators can dissect disease mechanisms, evaluate candidate interventions, and identify contributory genetic determinants. Genetically engineered animals reproduce discrete human phenotypes, thereby enabling detailed exploration of gene–environment interactions. Moreover, animal models permit systematic assessment of toxins, lifestyle factors, and additional environmental exposures on cerebral integrity. The knowledge generated with these systems informs the development of more effective therapeutics and ultimately improves clinical outcomes.