Computational analysis on FR258900 as dual-target inhibitor of bace-1 and acetylcholinesterase in treatment of Alzheimer's disease: A combined molecular docking and ADMET study

- Department of Pharmacy, Al-Zahrawi University College, Karbala, Iraq

Abstract

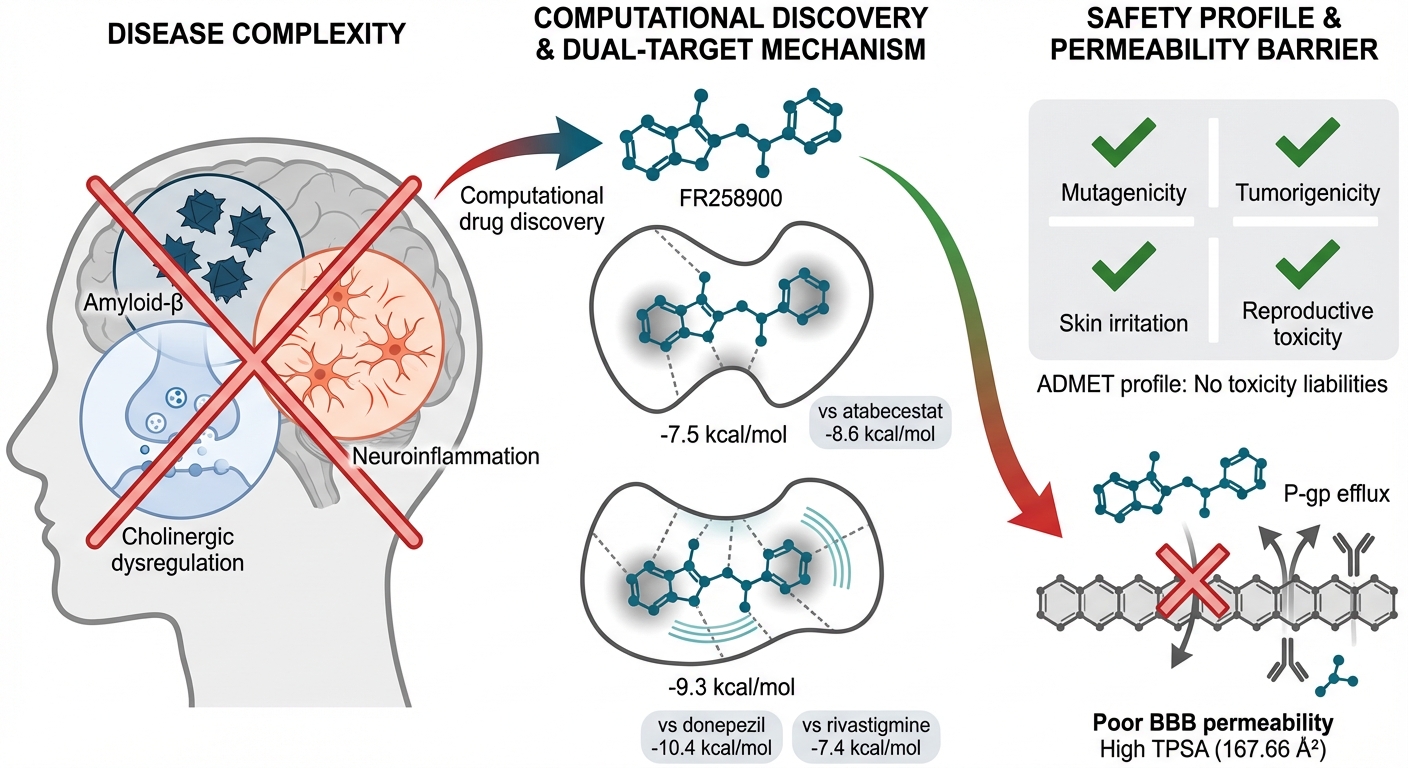

Introduction: Alzheimer's disease (AD) has a multifactorial pathogenesis. Single-target agents targeting amyloid-β accumulation or cholinergic dysfunction have limitations, necessitating novel therapeutic strategies. This study investigates the novel compound FR258900 to evaluate its dual-target inhibitory potential against BACE-1 and AChE.

Methods: The inhibitory profile of FR258900 was assessed by in silico molecular docking using the prepared crystal structures of human BACE-1 (PDB ID: 5HDZ) and AChE (PDB ID: 6TT0), from which non-essential atoms had been removed. Reference inhibitors were included for comparison. A comprehensive ADMET profile was generated using computational tools to evaluate pharmacokinetic properties, safety, ADME characteristics, and toxicity risks.

Results: The docking studies demonstrated favorable binding affinities of FR258900 for both BACE-1 and AChE. ADMET analysis forecasted low gastrointestinal absorption and poor blood-brain barrier penetration—probably attributable to P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux. The compound exhibited a satisfactory cytochrome P450 interaction profile and no predicted toxicity liabilities.

Conclusion: Although FR258900 exhibits unfavorable pharmacokinetic properties hindering central nervous system penetration, its low toxicity and dual-target inhibition of BACE-1 and AChE position it as a promising lead compound. Further optimization is warranted to advance FR258900 as a multitarget-directed ligand for the treatment of AD.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a multifaceted, progressive neurodegenerative disorder with a complex pathogenesis involving amyloid-β (Aβ) deposits, neurofibrillary tangles, cholinergic dysregulation, and neuroinflammation 1. The complex pathogenic factors of AD have led researchers to shift their approach from a one-drug, one-target model to a multi-target-directed ligand (MTDL) approach, targeted at modulating multiple disease pathways 2. Current therapeutic strategies for AD primarily employ a symptomatic approach, using agents targeted at enhancing cholinergic transmission, such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChE Inhibitors), for example, Donepezil, Rivastigmine, and galantamine, although these agents alleviate symptoms but do not alter the underlying disease process 2. The failure of monotherapeutic interventions has become increasingly apparent following the disappointing outcomes of single-target clinical trials, notably the multiple failures of β-site amyloid precursor protein cleavage enzyme 1 (BACE-1) inhibitors (verubecestat, lanabecestat, and atabecestat) 3. Multitarget-directed ligands (MTDLs) have emerged as novel drug leads for AD therapy, capable of acting synergistically by targeting multiple pathological pathways simultaneously 4. Dual targeting of AChE and BACE-1 represents the most popular and widely studied strategy for developing dual-target drugs that inhibit AChE and BACE-1 simultaneously. This approach addresses both cholinergic dysfunction through inhibition of AChE and amyloidogenic processing through inhibition of BACE-1 5.

Early successes in developing dual-target drugs have shown that preclinical studies can achieve promising results. The success of combination therapies, including the FDA-approved Namzaric™ (memantine and Donepezil), confirms the value of a multitargeting approach and provides a basis for creating single-molecule, multitarget-directed designs 6. Combining computational methods with natural product screening offers unique opportunities unavailable to traditional medicinal or combinatorial chemistry 7. FR258900, first isolated and purified from the fungal strain No. 138354, is a prime example of rediscovering natural products for multi-target therapies 8. Initially identified as a potent glycogen phosphorylase inhibitor with a K = 0.46 ± 0.06 μM, FR258900 exhibited potent hypoglycemic effects in diabetic animals through its allosteric inhibition of glycogen phosphorylase 9. The compound binds to the allosteric activator site, to which the physiological activator AMP binds, and induces conformational changes that favor the inactive T-state of the enzyme 10. The repurposing of FR258900 from diabetes to Alzheimer disease, as a second indication, underscores the potential of computational drug repurposing methods. The complex molecular architecture (C₂₃H₂₀O₁₀, MW 456.4 Da) and polypharmacological nature of the compound make it a promising dual-target inhibitor candidate for evaluation against both BACE-1 and acetylcholinesterase 11. Computational assessment of FR258900 as a dual-target inhibitor is a significant step forward in the multitarget-directed discovery of AD drugs. Such a strategy is of great importance, as one of the most critical issues in treatment is ensuring that the drug has favorable pharmacokinetic properties and can modulate multiple signaling pathways simultaneously 12. In this context, combining natural product chemistry with computational drug design offers valuable approaches for designing more effective drugs to treat AD, a multifactorial disease 13.

Methodology

Software and Hardware

A range of computational tools and online databases were used in the present study to perform molecular docking. Ligands and 3D target protein structures were retrieved from PubChem 14 and the Protein Data Bank (PDB; ID 15), respectively. The pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles of the hit compounds were estimated using SwissADME 16 and DataWarrior 4.7.3 (OSIRIS). All molecular docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Tools 1.5.6, and the proteins and ligands were visualized and optimized using BIOVIA Discovery Studio.

Protein Target Selection and Preparation

The protein targets selected for this study were BACE-1 (β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1; PDB ID: 5HDZ) and AChE (acetylcholinesterase; PDB ID: 6TT0), both of which play demonstrable roles in the neurodegenerative disease pathophysiology. Human (Homo sapiens) proteins were exclusively selected to ensure biological relevance. Before docking, all water molecules and heteroatoms were removed from the protein structures to prevent interference with the ligand-binding simulations.

Retrieval and Preparation of Ligands

The ligands subjected to docking were Atabecestat, FR258900, Donepezil, Rivastigmine, and Physostigmine. Each ligand retrieved from the PubChem database was downloaded in SDF format, subsequently converted to PDB format, and optimized using BIOVIA Discovery Studio. This preparation was necessary to achieve appropriate geometry and reduce steric clashes, thereby improving the accuracy of docking outcomes.

Identification of Active Sites and Grid Box Size Definition

The active sites of the two proteins were identified using the PDBsum database 17, which provides information on protein–ligand binding sites. The identified active-site residues were used to define each protein's docking grid box parameters. For BACE-1 (PDB ID 5HDZ), the grid box was centered at 19.9762 Å (X), 8.4827 Å (Y), and 25.0480 Å (Z), with 29.6790 Å × 20.7029 Å × 25.0000 Å as the dimensions, while for AChE (PDB ID 6TT0), the grid box was centered at −1.5667 Å (X), 63.6226 Å (Y), and 293.1143 Å (Z), with dimensions of 31.8679 Å × 32.8510 Å × 32.7097 Å. The grid spacing was 0.375 Å to ensure full coverage of the binding sites.

Molecular Docking Procedure

To evaluate the binding strength and inhibitory potential of the selected ligands against BACE-1 and AChE, molecular docking studies were performed using AutoDock Tools 1.5.6. The docking process was optimized using the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA), a robust approach that enables efficient exploration of ligand conformations. Each ligand underwent 100 independent docking runs to ensure thorough sampling of possible binding poses. The LGA parameters were set to 2.5 × 10⁶ energy evaluations and 27,000 generations per run, yielding reliable, reproducible results. Before docking, all protein structures were prepared by adding polar hydrogens and assigning Kollman-united-atom partial charges. A grid box was defined to encompass the active site region, ensuring accurate docking simulation accuracy. After the docking runs completed, the results were ranked by binding free energy. The conformation with the lowest binding free energy was considered the most favorable and selected as the optimal binding pose.

ADME Properties Assessment

The SwissADME web server was used to evaluate the ADME profiles of the selected ligands. Ligand structures were prepared and converted to SMILES, which were then submitted to the SwissADME server to generate advanced ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) profiles. These data were reviewed in a structured manner to support the identification of promising drug candidates with appropriate pharmacokinetic profiles.

Toxicity Risk Evaluation

The potential toxicity hazards of each ligand were evaluated using DataWarrior 4.7.3 (OSIRIS). Mutagenicity, tumorigenicity, irritancy, and reproductive toxicity were assessed using their corresponding ligand SMILES representations. These assessments were recorded and compared to determine which compounds were the safest.

Visualization and Analysis

The docking simulation results were visualized and analyzed using BIOVIA Discovery Studio. The ligand–protein interactions and binding poses were carefully scrutinized, binding affinities compared, and the most promising compounds selected for further investigation. This comprehensive strategy enabled us to elucidate molecular interactions that mediate ligand efficacy and specificity.

Results

This study aims to evaluate the therapeutic potential of FR258900 by comparing its molecular recognition and AutoDock binding affinities to two AD-relevant enzymes, AChE (PDB ID: 6TT0) and BACE-1 (PDB ID: 5HDZ), and by assessing its inhibitory efficacy relative to known inhibitors, such as Atabecestat for BACE-1. Simultaneously, for AChE, Donepezil, Rivastigmine, and Physostigmine were selected to enable an objective comparison.

The molecular properties of FR258900 and the reference compounds are presented in

List of Investigated Compounds and Their Molecular Properties

| Ligand | Molecular formula | PubChem CID |

|---|---|---|

| Atabecestat | C18H14FN5OS | 68254185 |

| FR258900 | C23H20O10 | 11669698 |

| Donepezil | C24H29NO3 | 3152 |

| Rivastigmine | C14H22N2O2 | 77991 |

| Physostigmine | C15H21N3O2 | 5983 |

Detailed physicochemical properties of all compounds are summarized in

Physicochemical Properties of the Selected Compounds

| Ligand | MW | No Rotatable bonds | NoH-bond acceptors | NoH-bond donors | Consensus Log P | Log S | TPSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atabecestat | 367.4 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2.23 | -3.44 | 129.46 |

| FR258900 | 456.4 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 2.02 | -3.82 | 167.66 |

| Donepezil | 379.49 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 4 | -4.81 | 38.77 |

| Rivastigmine | 250.34 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 2.34 | -2.69 | 32.78 |

| Physostigmine | 275.35 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1.65 | -2.57 | 44.81 |

ADMET Properties of FR258900. The ADMET parameter values listed in

Predicted Absorption, Distribution, and Metabolism (ADM) Parameters

| Ligands | GI absorption | BBB permeant | Pgp substrate | CYP1A2 inhibitor | CYP2C19 inhibitor | CYP2C9 inhibitor | CYP2D6 inhibitor | CYP3A4 inhibitor | log Kp (cm/s)(Skin permtion) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atabecestat | High | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | -7.14 |

| FR258900 | Low | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | -7.2 |

| Donepezil | High | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | -5.58 |

| Rivastigmine | High | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | -6.2 |

| Physostigmine | High | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | -6.86 |

As shown in

Toxicity Assessment of Compounds Using In Silico Methods

| Ligand | Mutagenicity | Tumorigenicity | Skin irritation | Reproductive effective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atabecestat | Safe | Safe | Safe | Safe |

| FR258900 | Safe | Safe | Safe | Safe |

| Donepezil | Safe | Safe | Safe | Safe |

| Rivastigmine | Safe | Safe | Safe | Safe |

| Physostigmine | Safe | Safe | Safe | Safe |

The AutoDock binding energy scores of FR258900 and its reference compounds to the target enzymes are presented in

Autodock Binding Energy Scoring Values of Compounds on AChE and BACE-1

| Protein (PDB ID) | Ligands | Binding Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| BACE-1(5HDZ) | Atabecestat | -8.6 |

| FR258900 | -7.5 | |

| AChE(6TT0) | Donepezil | -10.4 |

| FR258900 | -9.3 | |

| Rivastigmine | -7.4 | |

| Physostigmine | -8.5 |

This observed difference falls within the typical error range of docking tools such as AutoDock and AutoDock Vina, so it is not necessarily indicative of a genuine affinity improvement or reduction but could be within computational uncertainty.

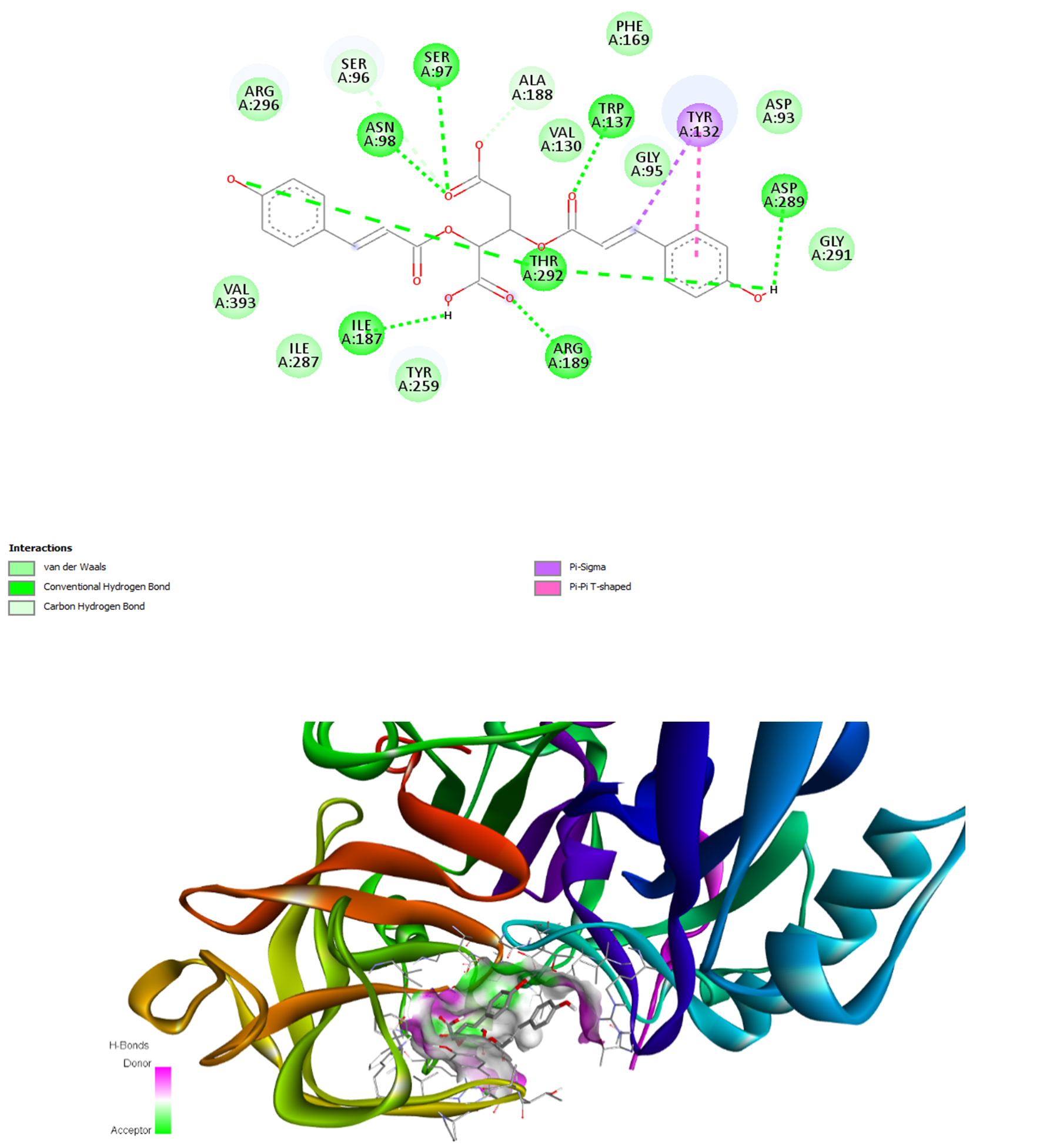

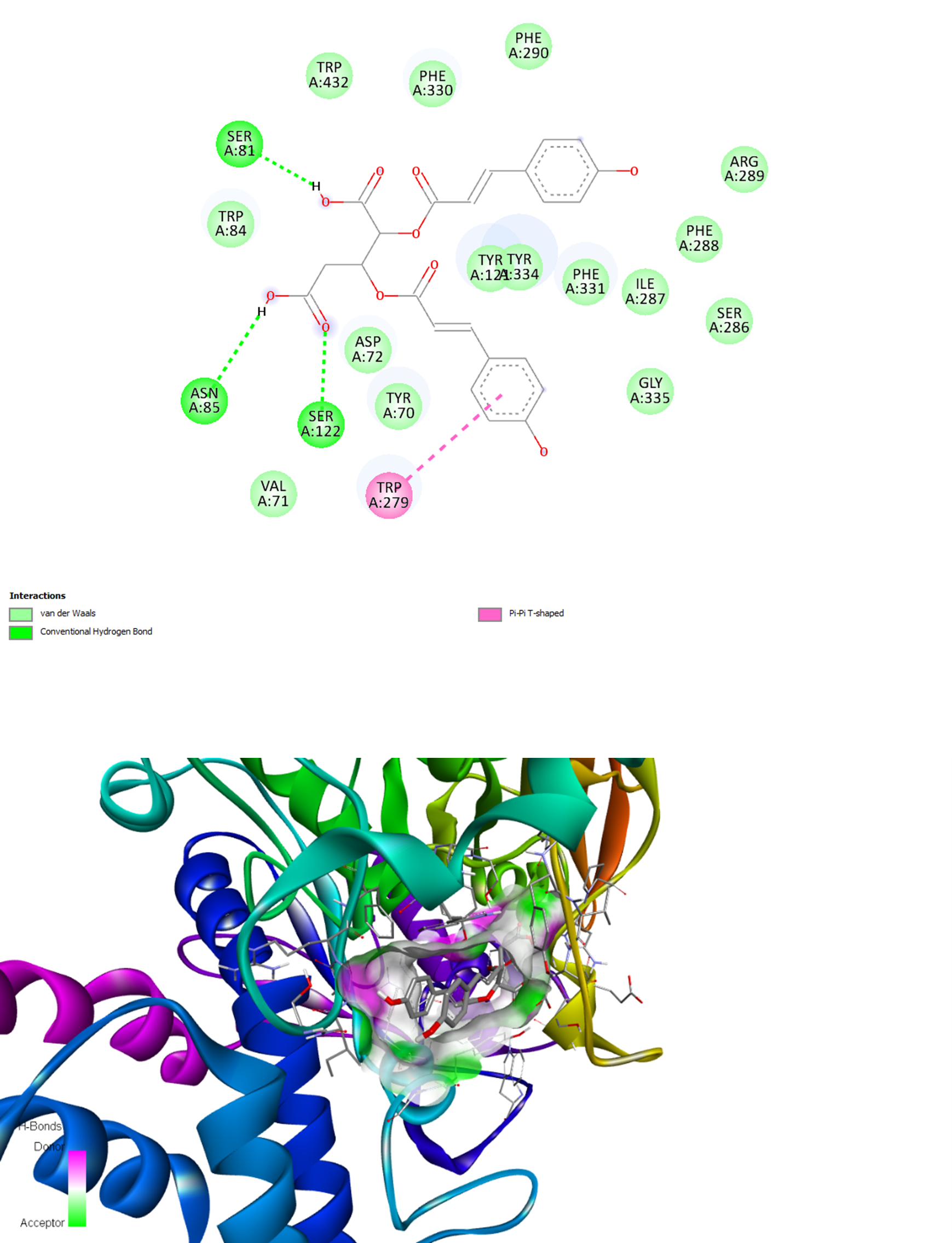

The binding interactions of FR258900 with the two target enzymes are visualized in Figures 1 and 2. In the BACE-1 complex, FR258900 participates in numerous stabilizing interactions, including van der Waals, conventional hydrogen bonds, and carbon–hydrogen bonds. The compound further establishes pi–pi T-shaped interactions with Tyr292 and pi–sigma interactions with Tyr132, thereby forming a complete active-site binding network. As shown in Figure 2, the binding interactions of the AChE complex demonstrate equally intense intermolecular contacts through conventional hydrogen bonds, extensive van der Waals contacts, and a pi-pi T-shaped interaction with Trp279. These interaction modes are consistent with those of known inhibitors, demonstrating that FR258900 can interact with the conserved active-site residues of both target enzymes.

Integrated 2D and 3D Visualization of FR258900 Binding Mode As Well as Interactions with Human β-Secretase 1 (BACE-1, PDB ID: 5HDZ)

Total 2D and 3D View of the FR258900 Binding to Human AChE (PDB ID: 6TT0)

Discussion

Results from this systematic analysis of FR258900 as a dual-indication therapeutic candidate for AD provide practical insights into the complexity and opportunities of multitargeted drug discovery for AD. This work exemplifies the potential and limitations of multitargeted AD treatment. It emphasizes the key pharmacokinetic obstacles that must be overcome to successfully translate it to the clinic.

The molecular docking results reveal that FR258900 exhibits a balanced dual-target inhibition profile, with binding affinities of -7.5 kcal/mol for BACE-1 and -9.3 kcal/mol for AChE. This dual engagement represents a significant conceptual advance over single-target approaches, as it simultaneously addresses both the cholinergic dysfunction and amyloidogenic processing pathways implicated in AD pathogenesis. The compound outperforms established AChE inhibitors such as rivastigmine (-7.4 kcal/mol) and physostigmine (-8.5 kcal/mol) while maintaining moderate BACE-1 inhibition, suggesting potential therapeutic advantages over current monotherapies. The multi-target drug design (MTDD) strategy used in this study is consistent with the increasing awareness that AD therapy may need to progress from single-target interventions to balanced, multi-target approaches3,4. Some single-target drugs, such as BACE-1 inhibitors, have repeatedly failed in clinical trials despite excellent target engagement in the brain 18. The inability of compounds such as lanabecestat, atabecestat, and solanezumab to affect disease progression has highlighted the narrow scope of targeting single pathways 18,19. Conversely, FR258900's dual-targeting profile may exert synergistic effects by reducing amyloid production and enhancing cholinergic function, thereby more effectively addressing AD's complex pathophysiology. Numerous dual-targeting compounds have demonstrated preclinical efficacy in recent years. Sharma et al. (2022) synthesized caffeine-based triazole derivatives with dual inhibition. Their representative compound 6d simultaneously inhibited AChE and BACE-1 with IC values of 1.43 and 10.9 μM, respectively20. Similarly, Zhai et al. synthesized dual-target inhibitors through structural modification of baicalein, yielding arylcoumarin derivatives that exhibited enhanced potency against both targets21. These results suggest that FR258900's dual-targeting ability offers a promising clinical strategy. Extensive molecular interaction networks underlie FR258900's duality, as evidenced by the alignment of its complex structures with BACE-1 and AChE. The compound binds to the BACE-1 active site through stabilizing hydrogen bonds and π-π interactions. This binding mode resembles that of known BACE-1 inhibitors, further supporting the compound's capacity to engage the catalytic machinery. Likewise, the AChE binding involves hydrogen bonds, van der Waals contacts, and a π-π (T-shaped) interaction with aromatic residues. These interactions resemble the binding modes of the clinically approved AChE inhibitor donepezil, which displays multiple binding modes in the AChE active site gorge and adopts varied conformations22, indicating that FR258900 functions as an AChE modulator. Recent computational studies demonstrate that dual-target ligands must possess sufficient conformational flexibility to accommodate varying binding-site geometries 23. Although this may pose selectivity challenges, the 12 rotatable bonds in FR258900 facilitate fitting into both target sites. Such flexibility is an essential consideration in designing multi-target compounds, enabling adaptation to various binding pocket geometries without sacrificing affinity at any single target.

FR258900 exhibits suboptimal pharmacokinetic properties despite favorable target engagement—a key barrier to clinical translation. The prediction of non-BBB permeability reflects challenges with other high-molecular-weight molecules in CNS disorders24. The high TPSA value of 167.66 Ų exceeds the typical threshold (<90 Ų) for passive BBB penetration25. The blood-brain barrier, impeding ~98% of small molecules and nearly all large therapeutics26, poses a major obstacle in CNS drug development. For AD therapeutics, poor brain penetration reduces efficacy and increases peripheral side effects27. Notably, several BACE-1 inhibitors failed clinically despite adequate CNS penetration and high peripheral engagement28. Insights into P-glycoprotein function suggest strategies to enhance CNS penetration; carboxylic acid conjugates evade P-gp efflux with >85% probability29. Structural modifications could thus improve FR258900's BBB permeability. Furthermore, novel delivery approaches—nanoparticles, focused ultrasound-mediated BBB disruption, and intranasal administration—show promise for CNS drug delivery30.

FR258900's balanced dual-target profile aligns with the consensus that multitarget therapy is essential for effective AD treatment. Its influence on divergent cholinergic and amyloidogenic pathways marks progress beyond symptom-focused cholinergic therapies. This dual action may enable disease modification by addressing amyloid metabolism and cholinergic deficits. Clinical success of combination therapies, such as FDA-approved Namzaric™ (memantine + donepezil), supports multitarget strategies for AD31. Yet, FR258900's single-molecule approach may confer advantages over combinations, including improved adherence, reduced drug-drug interactions, and simplified dosing. Its favorable toxicological profile (non-mutagenic, -tumorigenic, or -reproductive toxicant) enhances clinical feasibility. Multitarget drug discovery has flourished recently, with multiple successes32. Integration of advanced computational tools, such as machine learning-based ADMET prediction and molecular dynamics simulations, has enhanced design precision33, enabling rational optimization of candidates like FR258900. This study contributes to insights on AD drug discovery needs, emphasizing integration of target engagement and pharmacokinetics. Limitations include reliance on docking, which may not capture protein-ligand dynamics34. In vitro validation via cellular assays is required to confirm activity and selectivity. Future efforts should prioritize medicinal chemistry to mitigate pharmacokinetic deficits. FR258900's pharmacokinetic profile limits CNS potential, primarily due to poor predicted BBB permeability from high TPSA and P-glycoprotein substrate status. This flaw necessitates optimization—structural modifications to reduce polarity, prodrug strategies for lipophilicity, or advanced delivery systems (e.g., nanoparticles, intranasal)—as essential steps toward clinical viability. Ultimately, integrating computational design, delivery innovations, and precision medicine is required to deliver effective AD therapeutics.

Conclusion

FR258900 exhibits promising dual-target inhibitory activity against BACE-1 (–7.5 kcal/mol) and AChE (–9.3 kcal/mol), demonstrating superior AChE binding affinity compared with rivastigmine and physostigmine. The compound exhibits an excellent predicted safety profile, predicting no toxicity and thereby supporting its potential advancement to clinical development. However, significant pharmacokinetic challenges—particularly low blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration arising from a high polar surface area (167.66 Ų) and its P-gp substrate status—necessitate structural optimization. All presented results are based on computational predictions and therefore require validation by experimental methods, such as in vitro enzyme inhibition assays and cell-based BBB permeability studies. These validations are crucial for substantiating the in silico findings and assessing the translational therapeutic potential of FR258900. Despite these limitations, FR258900 represents a promising lead compound for multi-target-directed (MTD) therapy against Alzheimer's disease and can be further developed through medicinal chemistry optimization to improve CNS penetration without compromising its dual-target activity.

Abbreviations

Aβ: amyloid-β; AChE: acetylcholinesterase; AD: Alzheimer's disease; ADME: absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion; ADMET: absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity; BBB: blood-brain barrier; BACE-1: β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1; CNS: central nervous system; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; GI: gastrointestinal; LGA: Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm; MTDL: multi-target-directed ligand; MTDD: multi-target drug design; PDB: Protein Data Bank; P-gp: P-glycoprotein; TPSA: topological polar surface area.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author’s contributions

All authors have contributed equally. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that they have not used generative AI (a type of artificial intelligence technology that can produce various types of content including text, imagery, audio and synthetic data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.