Limitations of artificial intelligence in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine

- Department of Regenerative Medicine, National Medical Research Radiological Centre of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 249031 Obninsk, Russia

- Obninsk Institute for Nuclear Power Engineering, National Research Nuclear University MEPhI, Obninsk, Russia

- Department of Engineering, Russian University of Transport (MIIT), Moscow, Russia

- Scientific and Educational Resource Center for Innovative Technologies of Immunophenotyping, Digital Spatial Profiling and Ultrastructural Analysis, Patrice Lumumba Peoples Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), 117198 Moscow, Russia

- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), 119435 Moscow, Russia

- Institute for Systems Biology and Medicine, Russian University of Medicine, Moscow, Russia

Abstract

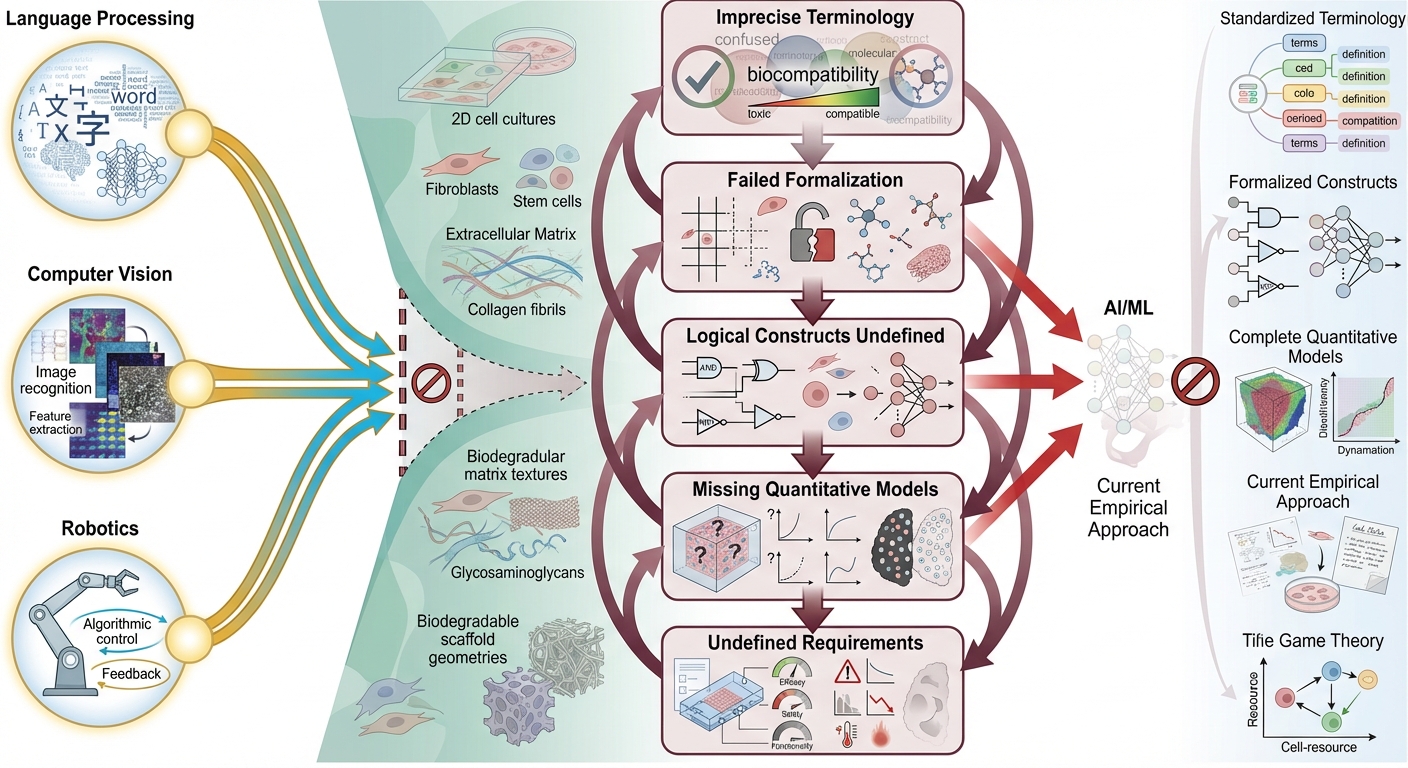

Designing and understanding the organizational principles of living tissues requires the integration of diverse knowledge and skills owing to the extreme complexity of biological systems. This complexity makes predicting tissue behavior and dynamic properties particularly challenging. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have emerged as powerful tools for addressing these challenges. They have demonstrated success in fields including natural language processing, computer vision, fraud detection, autonomous systems, and robotics. However, their application to tissue engineering and regenerative medicine (TERM) presents unique domain-specific challenges that remain unresolved. This narrative review identifies and discusses five critical limitations that currently hinder the effective integration of AI and ML into TERM, namely: (1) imprecise terminology in biology, (2) lack of formalized concepts and terminology in TERM, (3) absence of clear logical constructs in the field, (4) limited development of quantitative physiology, and (5) lack of quantitative requirements for applying engineering principles.

Introduction

A deep understanding of the principles underlying living organisms remains elusive, and novel approaches are needed. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) has given researchers hope of applying these technologies to various fields, including tissue engineering and regenerative medicine 1,2. To date, AI-based solutions, such as ChatGPT and DeepSeek, have already been applied to natural language processing, computer vision, fraud detection, virtual assistants, autonomous vehicles, and robotics. Studies on AI applications in tissue engineering currently focus on solutions for structure-function relationships, material design, scaffold and device fabrication, and cell patterning 3,4,5. Most studies have concluded that machine learning models are well-suited for analyzing large, high-dimensional data, and that certain biological relationships can be readily analyzed using traditional statistical methods 1,6.

Therefore, AI holds promise as a unique tool for advancing the development of artificial organs and tissues, which are currently facing considerable challenges. Initially, it was expected that neural network models would contribute significantly to the development of bioengineering techniques7, but relevant principles have not yet been developed. Only a few such models based on engineered principles can be found in tissue engineering applications, such as finite element models 8,9,10, the phase space method 11, the minimax method 12, failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) 13, reliability engineering 14, and design for manufacturability 15,16. The absence of AI-based generative models for tissue engineering and the design of human organs has led to substantial restrictions in this field. On the other hand, synthetic morphogenesis is a promising concept for overcoming limitations in tissue engineering approaches 17, but it has encountered challenges in genome organization and has yet to lead to significant breakthroughs in the field.

There are some interesting studies on the applications of AI in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine (TERM). For instance, computational methods are used to model scaffolds for neural tissue engineering. The finite element method (FEM) has been identified as an essential tool for modeling the boundaries and initial value problems that are characteristic of many physical processes related to the functioning of tissue-engineered scaffolds 18. However, FEM is a standard mathematical modeling procedure, so the benefits of AI integration are unclear.

A created convolutional neural network architecture is efficient at detecting and predicting continuous values for DNA and protein concentrations 19; however, this method is related to regression analysis because it is questionable and depends on initial conditions. A deep learning–based inverse design framework for disordered cellular materials (Voronoi lattices) with the desired target relative density and Young's modulus was developed for three-dimensional architected cellular materials 20. The applications and implications of artificial intelligence in regenerative medicine state that ‘AI has emerged as a powerful tool that analyzes the physicochemical and biological properties of a wide range of materials to predict the most successful outcomes’ and that ‘AI algorithms can identify patterns and associations in cellular behavior and interactions, thereby enabling the prediction of cell behavior in different environments’; however, these claims are not presented with evidence to support them 21. For example, studies on resorbable scaffolds for oral and maxillofacial tissue engineering have not offered examples or approaches for scaffold design 22.

The limited results obtained in these studies are unsurprising. A little-known property of complex systems is that “several simulation studies have found that using logistic regression for propensity score modeling can result in biased treatment effect estimates when the model is misspecified, especially in complex data where non-linear and non-additive terms are not included in the propensity score model. This situational bias occurs because parametric models, such as logistic regression, require assumptions about covariates’ functional form and distribution. When estimating propensity scores with many covariates, this problem can be particularly pronounced” 23. This means that the use of AI-based models for analyzing complex systems is preconfigured and thus subject to configuration-related limitations. For instance, Catalanotti, G. (2024) demonstrated success in contexts where the functions of relations between parameters have clear definitions 24. Unfortunately, this principle, rooted in information theory, is often overlooked by some researchers. Essentially, the critical question is whether physiological responses can be categorized as definite or indeterminate.

Moreover, the problem may be more profound because some researchers believe that modern mathematics is ineffective in biology 25, and that applying AI to biological problems is unsuccessful by definition, primarily due to the absence of a new kind of AI that uses methods of proof theory to provide justifications along with answers. This approach differs from calculation-based AI, machine learning, and data science methods.

Current AI models use correlation matrices to analyze large datasets, which are sensitive to initial values and boundary conditions 26. This highlights the intricate relationship between data structure and predictive accuracy. This sensitivity underscores the importance of carefully selecting and processing initial data because minor variations can lead to significantly different outcomes. Previous studies have shown the ineffectiveness of applying mathematical approaches in biology 25,27, indicating that understanding biological processes requires developing a new mathematical language 27. These aspects are likely the main cause of mathematics' unreasonable ineffectiveness in biology 25,28. The challenge lies in capturing the dynamic and often nonlinear nature of biological processes and translating these complex phenomena into a precise and flexible mathematical language that can capture the nuances of living systems.

Currently, approaches are being developed for designing and producing biological networks from high-level program specifications 29. However, the absence of engineering approaches in tissue engineering makes it seemingly impossible to adequately apply these methods 30. This review describes essential steps for applying machine learning and AI to achieve breakthroughs in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Advances and limitations of AI in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine

Imprecise Terminology in Biology and Tissue Engineering

The efficacy of AI models, particularly large language models, relies heavily on precise and standardized terminology. The absence of commonly accepted terminology and standards can render machine learning applications inadequate. For example, the concept of biocompatibility has multiple interpretations 31, thereby complicating biomaterial development absent detailed descriptions ensuring interpretability.

An additional barrier to AI applications arises from terminological imbalance. Recognizably, advances in the previous four critical areas remain predominantly introductory, such that machine learning models remain constrained by prevailing terminology. Correlational AI solutions trained on existing datasets are thus limited by such terminology and cannot achieve substantive breakthroughs. For example, employing AI to analyze complex systems featuring parameters with indeterminate distribution functions, coupled with unknown a priori causal relationships—e.g., in quantitative physiology, morphogenesis, and gene regulation, wherein inter-parameter relationships remain unknown—is unlikely to confer significant benefit 32. Conversely, beneficial results manifest primarily when underlying functions are well defined, even if distribution functions remain indeterminate 22,24,33,34. Moreover, where causal relationships are firmly established, AI applications demonstrate efficacy 35,36, as predicted by information theory. Consequently, existing studies and reviews on AI in tissue engineering tend to be superficial and lack novelty.

Prior to implementing machine learning for feature analysis and extraction from tissue-level data, elucidating simple structure–function relationships in biological systems, or employing machine learning to correlate tissue-level findings with clinical data, precise resolution of imprecise terminology in biology, tissue engineering, physiology, and medicine is essential to enable term formalization.

Lack of Term Formalization

Physiology is a broad and interdisciplinary field that has evolved over centuries. Terms and concepts derive from various languages, cultures, and historical periods in physiology and related fields, yielding diverse yet complex terminology. The historical evolution of physiology and biology has produced synonymous terms for multiple concepts or organisms, contributing to confusion and inefficiency in communication and learning 37. This interplay of science, history, and language highlights the dynamic nature of physiology as a discipline shaped by its history yet advancing knowledge.

Understanding the principles of physiology requires a focus on the deep underlying mechanisms, potentially based on symmetries and conservation laws in biological systems 38. Symmetries in living organisms are well-known and elucidated, as are those in biochemical reactions 39. Noether's theorem states that every symmetry corresponds to a conservation law, which could apply to macroscopic pubs or their properties40; thus, there are no theoretical limits to formalizing biological interactions in biological systems. This lack of term formalization is evident in the AI-based development of organoids, where AI integration enables efficient organoid construction, multiscale image analysis, and precise preclinical evaluation 41.

Biochemical symmetry is another potentially fruitful concept for elucidating the persistence and stability of biochemical reactions. Biochemical reaction networks often contain duplication, which manifests as symmetry in the underlying hypergraph 39,42. The nature of biochemical symmetry encompasses both the structural and functional symmetry observed in biological molecules and complexes 43, potentially underpinned by these conservation laws. Therefore, the lack of term formalization prevents the development of the logical constructs required for design and engineering.

Absence of Logical Constructs in Tissue Engineering

Tissue engineering integrates principles of biology, engineering, and computer science to create or repair human tissues. This engineering approach requires formally defined rules and constraints 44. However, developing quantitative physiological models requires specialized logical constructs essential for data markup and comprehensive understanding of underlying processes. Such logical constructs facilitate the design of algorithms for deep learning models that handle data processing, noise filtration, and development of reasoning methodologies.

Although biological rules are grounded in a deep understanding of biological processes and their operational constraints, developing quantitative physiological models remains central, providing a structured framework for exploring and manipulating the intricacies of biological systems. These models rely on specialized logical constructs for data representation and facilitating comprehensive understanding of biological phenomena.

Incorporating logical constructs in tissue engineering and quantitative physiological modeling is indispensable 45. They offer a framework through which data can be annotated and understood, and facilitate the creation of algorithms essential for field advancement. Deep learning models, now increasingly significant, depend on these algorithms to process vast amounts of data, filter out noise, and extract meaningful patterns 46. However, integrating reasoning methodologies in AI systems presents a notable challenge, without which AI struggles to perform critical data analysis tasks such as parsing, clustering, principal component analysis, approximation, and projection. These tasks are essential for interpreting data from tissue engineering research and informing the design of new experiments and interventions.

The robustness observed in living systems, such as genomic stability, hints at undiscovered logical constructs that could play a pivotal role in morphogenesis—the process by which an organism's shape develops 47. This suggests that nature employs complex logical frameworks to govern the growth and development of living organisms, potentially revolutionizing biological understanding and the development of advanced models in tissue engineering.

The absence of logical constructs is not universal in all areas of tissue engineering. In particular, for quantitative physiological models, logical constructs are already a fundamental component. These models inherently incorporate structured logic to simulate physiological processes, thereby distinguishing them from other areas of tissue engineering where their integration remains nascent. Conversely, the lack of reasoning methodologies in AI makes it impossible to adequately conduct parsing, clustering, or principal component analysis, approximation, and projection on data. The observed robustness in living systems, linked to genomic stability, could indicate undiscovered logical constructs that govern morphogenesis 48.

Consequently, the paucity of logical constructs in key areas of tissue engineering limits the development and application of quantitative physiological models.

Insufficiency of Quantitative Physiology

The insufficiency of quantitative physiology not only hampers the development of artificial organs in tissue engineering but also limits the advancement of predictive models essential for preclinical testing of new treatments and interventions 50. The reliance on qualitative descriptions and the absence of precise, numerical data on complex interactions within human tissues have led to significant gaps in our ability to create effective and reliable tissue-engineered products.

One of the critical areas where this insufficiency is particularly evident is in the understanding of the mechanical properties of tissues and their interactions with implanted devices or engineered tissues 51. The biomechanical environment of cells, including such factors as stress, strain, and fluid flow, plays a critical role in cell behavior, differentiation, and tissue development. The dynamic nature of living tissues, characterized by continuous remodeling and regeneration, adds another layer of complexity. Quantitative physiology could provide insights into the kinetics of these processes, enabling the design of engineered tissues that can adapt to and evolve within the host body.

Absence of robust quantitative frameworks leads to an inadequate interface for understanding human physiology, making it impossible to predict the behavior of implanted artificial organs. Quantitative human physiology is an approach that could greatly contribute to tissue engineering , extending beyond classic human anatomy and physiology 50,52. For instance, the poorly understood 3D spatial distribution of cells in living tissues is a challenge that remains unsolved in both developmental biology and tissue engineering 53. The distribution, migration, and chemotaxis of cells are key considerations in designing engineered tissue constructs. However, these distribution patterns are still unknown, and researchers are forced to rely on those of native organs. Some promising approaches have used cell label distribution to understand these principles, but these attempts are rare. Consequently, the lack of quantitative physiology precludes an understanding of the quantitative requirements for tissue-engineered constructs.

The field of systems biology aims to understand the complex interactions within biological systems through a combination of computational and experimental techniques. The development and use of mathematical models that can simulate the behavior of cells and tissues under various conditions allow researchers to gain insight into the underlying principles of tissue organization and function. However, these models require accurate and comprehensive quantitative data, highlighting the need for advances in quantitative physiology.

The Absence of Quantitative Requirements

It has previously been demonstrated that an lack of detailed requirements for tissue-engineered constructs can result in not only reduced efficacy of these medical devices, but also an increased risk of severe postoperative complications 54. Currently, existing standards for tissue-engineered organs primarily focus on ensuring their biological and physiological compatibility 55,56,57. However, the inability to predict the effectiveness of a specific design solely based on an analysis of individual material properties necessitates the development of clinical requirements to support the implementation of new technologies. The absence of quantitative requirements prevents the application of engineering terminology to formalize biological issues, which in turn hinders the implementation of AI models in tissue engineering.

This lack of detailed requirements for tissue-engineered constructs has significant implications for regenerative medicine and tissue engineering 58. This gap not only compromises the efficacy of these advanced medical devices but also increases the risk of serious postoperative complications, as highlighted in previous studies. Current standards for the design and evaluation of tissue-engineered organs focus primarily on ensuring their biological and physiological compatibility 59. The challenge in predicting the effectiveness of tissue-engineered constructs solely from the properties of individual materials underscores the need for comprehensive clinical requirements.

This gap notably affects the potential application of artificial intelligence (AI) models in tissue engineering. To bridge this gap, there is an urgent need for interdisciplinary collaboration between engineers, biologists, and clinicians. Such collaboration would facilitate the establishment of quantitative and qualitative requirements for tissue-engineered constructs. By integrating engineering principles and AI with tissue engineering, researchers can use computational models to simulate the biological behavior of engineered tissues, optimize their design, and predict their clinical outcomes. This approach would not only improve the efficacy and safety of tissue-engineered medical devices, but also accelerate the bench-to-bedside translation of these technologies from laboratory to clinic.

Synthesis of the necessary advances in AI for TERM development.

The necessary advances in AI for TERM development, as described above, were summarized in

Synthesizing ideas for necessary advances in AI for TERM applications

| Present state | Consequence for AI | Needed advance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Imprecise Terminology in Biology and Tissue Engineering | Many terms in the fields of biology and tissue engineering remain context-dependent and ambiguously defined. | AI models have difficulty aligning biological concepts and performing consistent annotations across datasets. | Create standardized, ontology-driven terminologies based on measurable biological features. |

| 2. Lack of Term Formalization | Key concepts are described in general rather than formal, machine‑ interpretable definitions. | Automated reasoning and data integration become either unreliable or impossible, resulting in divergent solutions. | Develop formal ontologies based on interconnected terms that precisely encode biological relationships. |

| 3. The Absence of Logical Constructs in Tissue Engineering | Lack of explicit, logical frameworks in tissue engineering that link structure, function, and material interactions (formalized terms). | AI-driven systems cannot logically predict outcomes or infer causal mechanisms. | Use rule-based and causal logic models to represent and test tissue-engineering hypotheses. |

| 4. Insufficiency for Quantitative Physiology | Biological models often omit quantitative physiological parameters or rely on oversimplified data. | Computational predictions tend to become less accurate and less general across biological scales. | Reformulate physiology as multi-scale, rigorously parameterized models. |

| 5. The Absence of Quantitative Requirements | Experimental designs and system specifications rarely define measurable success metrics. | AI tools cannot optimize or validate models based on objective performance criteria. | Establish explicit, quantitative benchmarks to guide the design, modeling, and evaluation processes. |

Discussion

Standard engineering approaches have utilized variational models, coordinate fields, the minimax principle, and other abstract mathematical concepts. However, these methods have not been adequately characterized in recent years. Moreover, manual manipulations are labor-intensive, complex, impractical, and exceed simple abstractible rules that can be formalized.

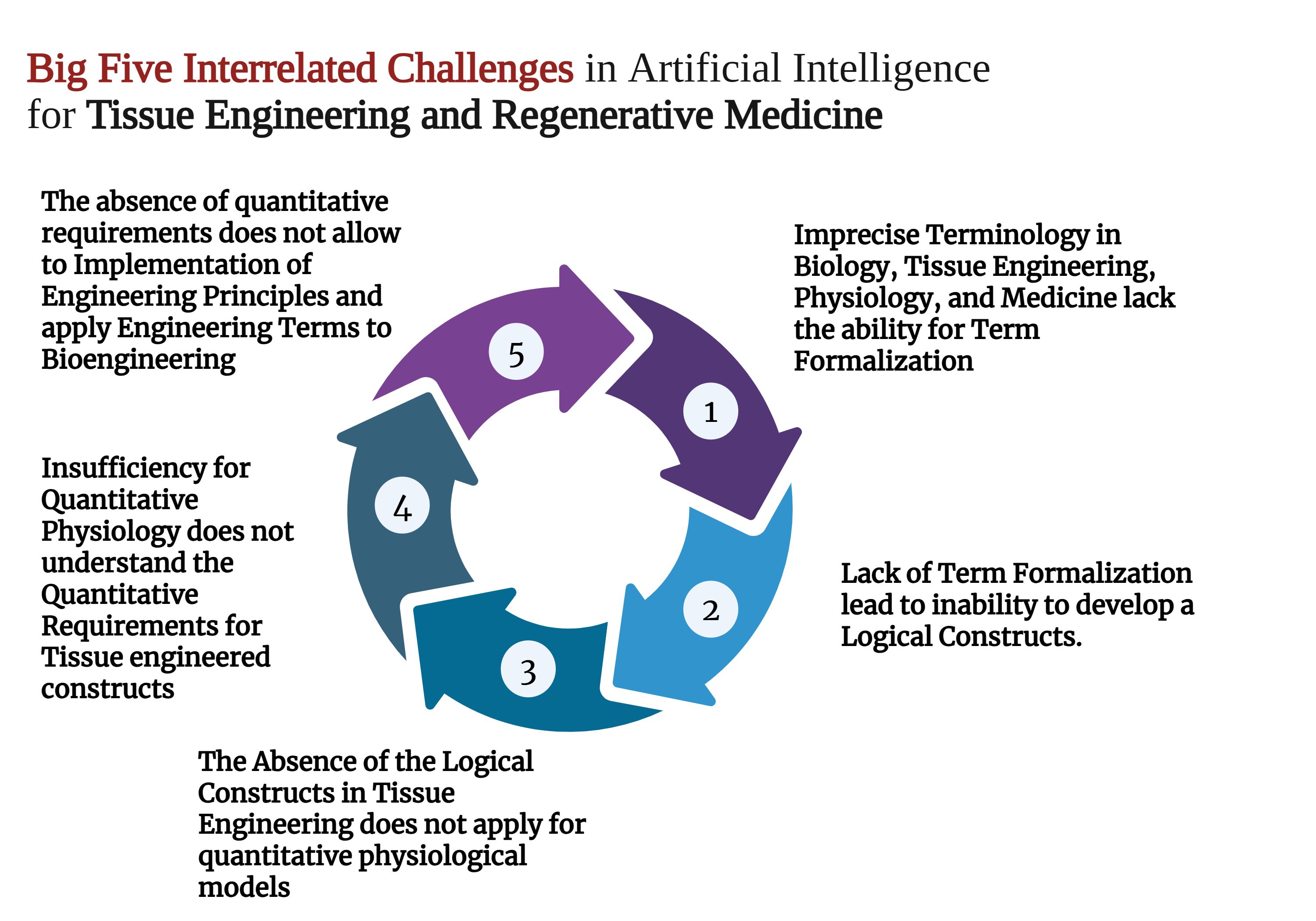

Despite years of attempts to establish tissue engineering as a rigorous engineering discipline, it remains largely empirical. The absence of regularities and valid limiting laws prevents the formulation of problems for which variational approaches could be used to find solutions. The potential of AI-based solutions is also limited by the need for biologically interpretable explanations of a model's output. Additionally, the effectiveness of such models in understanding underlying biological mechanisms and clinical applications is restricted 41,60,61. These issues can be summarized as the five challenges of artificial intelligence in tissue engineering (Figure 1).

Big Five Interrelated Challenges in Artificial Intelligence for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Created with

Attempts to quantitatively describe biological self-organization mechanisms have thus far failed to formulate consistent systems of equations. These attempts have focused on synthetic morphogenesis 62, the standard morphological element approach 63, group theory 64, non-cooperative game theory 65, and parametric symmetries and their implications 66. These limitations highlight the opportunity to apply deep learning-based correlation models to transition toward formalized engineering methods. However, genetic technologies can extend the framework of existence beyond genomics. Throughout history, science has shown that prediction requires understanding. Therefore, without understanding the mechanisms underlying morphogenesis and the development of living organisms, designing them will be impossible.

Contemporary approaches lack proven techniques for describing the behavior of biological systems. However, a number of studies on quantitative and logical relationships in living systems offer hope, including those on cell fate 67,68, division of labor in tissues 69, and principles of intertissue connections 70. Undoubtedly, the crucial breakthrough will be in mathematics and mathematical logic, which will explain the identified patterns and effects that have previously escaped researchers' attention. Indeed, collaborations between biologists and physicists are already underway to understand evolution as multi-level learning 71,72,73.

All of this suggests that insights from the field of self-organization of chemical systems could be pivotal. The optimal paths remain unclear, as are non-cooperative games in living tissues or reinvestigating functional anatomy. Variant anatomy introduces uncertainty regarding the robustness of anatomical patterns 74,75. Organs and tissues may not develop entirely according to a single morphogenesis program, but rather undergo natural, nonpathological changes. This suggests that such changes are subject to mechanisms governed by human genetics and epigenetics.

Developmental biology is the study of the natural growth of tissues and the interactions between progenitor tissues. During embryogenesis, cells are capable of proliferation and interaction, including symbiotic interaction 76. As expected, natural interactions in the early stages of development can maintain neonatal growth and development, and present an original, non-conventional approach to understanding human anatomy by examining interaction variances.

The origins of competition among human tissues during morphogenesis follow complex underlying mechanisms. For instance, it has been discovered that tissues compete for amino acids 77. Game theory is a tool for understanding cell behavior in multicellular organisms 78, cellular sociology 79, and division of labor in organisms 80. In brief, this approach can predict the outcomes of complex organ transplants and even symbiotic interactions between two or more tissues within one serous membrane.

Nobel laureate Peter Medawar described immunological patterns associated with cell-to-cell communication and immunological compatibility during pregnancy 81. The issue is that pregnancy resembles organ transplantation because the fetus possesses paternal antigens and is a semi-allogeneic graft that can survive without immunosuppression. Hypotheses have been proposed to answer the question of how a mother supports her fetus in utero, now known as "Medawar's Paradox." The mechanisms governing fetal-maternal tolerance are incompletely understood but may provide critical insight into achieving immune tolerance in organ transplantation 81.

Another crucial category of physiological responses to both external (exogenous) and internal (intrinsic) factors is represented by tissue competitions, and these highlight the dynamic interactions within multicellular organisms 82. These competitions are not merely localized events, but are significantly influenced by, and contribute to, the broader physiological context. This context encompasses various types of tissues and their interactions. Cross-tissue connections play a pivotal role in macrospatial responses, showcasing how tissues communicate and influence one another across different regions of the body 83.

Initially studied in the context of developmental biology and cancer research, cell competition has revealed the mechanisms by which cells compete for survival, dominance, and space 84,85. When extrapolated to the level of tissues and organs, these mechanisms suggest the broader applicability of competition and cooperation principles in shaping the architecture and function of multicellular organisms 86. However, the understanding and formalization of these principles are primarily limited by the lack of physiologically relevant engineering approaches. The absence of underlying principles and models limits the support machine learning systems can provide to researchers and impedes the physical creation of tissue engineered constructs using irrelevant methods, such as 3D bioprinting 87.

The perspective of tissue morphology formalization shifts the traditional view of organ and tissue interactions from a harmonious, cooperative framework to one that recognizes competition and cooperative dynamics as fundamental aspects of biological organization and function 88,89,90. This new understanding of conservation laws in living systems opens avenues for exploring how tissues and organs negotiate space, resources, and functional roles within multicellular organisms. This framework challenges the conventional notion of cell competition as solely a microscopic phenomenon, suggesting that it is also mirrored and amplified at the tissue and organ levels.

Conclusions

Despite the dramatic rise of artificial intelligence technologies and deep learning approaches, there is currently no place for their application in tissue engineering, partly due to the lack of solutions for general requirement issues. Before artificial intelligence models can be applied to novel and groundbreaking ideas in this field, they need to be thoroughly described through logical constructs, and multitested on large datasets.

Abbreviations

AI: artificial intelligence; FEA: failure mode and effects analysis; FEM: finite element method; ML: machine learning; TERM: tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 was created using Biorender.com service.

Author’s contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation, grant No. 25-24-20176.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that they have not used generative AI (a type of artificial intelligence technology that can produce various types of content including text, imagery, audio and synthetic data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.