Recent Advances in the Role of Microorganisms in Cancer Incidence: Mechanisms and Health Precautions

- School of Industrial Technology, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia

- Faculty of Science, Sabratha University, Sabratha, Libya

- Faculty of applied science, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, Malaysia

Abstract

Humans harbor various microorganisms, some of which reside naturally in the body, and some of which are transferred from elsewhere. Many of these microbes are considered to be normal flora that do not cause disease, provided that they occur only in their normal anatomical site in the body. The development of malignant lesions requires a long incubation time, even after direct exposure to known carcinogens. Multistep tumorigenesis is required to transform a normal cell into a cancerous one. The role of different microbes in tumorigenesis has expanded to include their potential capacity to form and modulate several cancer hallmarks, including the alteration of the immune response, tumor-promoting inflammation, angiogenesis, tumor growth and proliferation, and pro-carcinogenic metabolite production. Furthermore, microbes may damage the host DNA and induce genomic instability. This review provides a basic overview of the process of tumorigenesis and the role of different microorganisms in cancer accuracy. Then this study discusses the different mechanisms of tumor induction by viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and fungi. Finally, it highlights the necessary health precautions that need to be taken to prevent the development of cancers.

Introduction

Cancer is one of the most common diseases worldwide. It is the result of the uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells due to genetic mutations. Cancer develops when normal cells lose control of their proliferation. They keep growing and dividing rather than dying, and this forms a new, abnormal mass of tissue called a tumor1. Despite the advances made in oncological diagnoses, management, and therapy, there has been a steady increase in the number of cancer patients globally2. Many studies estimate that roughly 20–25% of all human malignancies worldwide are related to microbial infections3, 4. The role of different microbes in tumorigenesis has expanded to include their potential capacity to form and modulate several cancer hallmarks, including the alteration of the immune response5, tumor-promoting inflammation6, 7, angiogenesis8, tumor growth and proliferation9, and pro-carcinogenic metabolite production10. Furthermore, microbes may damage the host DNA and induce genomic instability11, 12. Various oncogenic mechanisms have been suggested for viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and fungi.

Recently, a number of review articles have discussed the mechanism of tumorigenesis for single microbes, including viruses13, bacteria14, protozoa15, and fungi16. Other reviews have comprehensively covered the role of microbes and their relation to cancer17, 18 and their effect on the human immune system19. To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive review has yet been published that discusses the role of all microorganisms in the incidence of cancer. The current review provides a straightforward overview of oncogenic microorganisms and the process of tumorigenesis. It explores different carcinogenic microorganisms and their mechanisms in cancer induction, and it also highlights the necessary health precautions that can be undertaken to prevent the development of cancer.

Mechanisms of microbial carcinogenesis

Microbial infections have recently been recognized as one of the top causes of many types of cancer, especially in undeveloped and developing counties due to poverty and unhygienic environments20. International cancer research agencies have classified infections due to eleven pathogenic species as Group 1 carcinogens. These include the hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, , , , , human papillomavirus, human T-cell lymphotropic virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus, and human herpesvirus21, 22. Most of the emphasis has been on viruses due to their direct influence on human genes23 and bacteria, which causes chronic inflammation leading to cancer24. Although fungi and parasitic protozoa have largely been overlooked, they are now being investigated as important factors in microbial carcinogenesis25, 26.

Carcinogenic viruses

The history of tumor virology began in 1911 with the discovery of a filterable agent capable of inducing sarcomas in chickens27. Later on, this filterable agent was shown to be a retrovirus that proved able to transduce a gene, and induce tumors. The beginning of human tumor virology came in the 1960s following the discovery of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)28 that was first observed using electron microscopy in cells cultured from Burkitt's lymphoma29.

International cancer research agencies have classified seven viral pathogens as highly carcinogenic agents. These agencies have also estimated that 1 in 10 cancers is caused by viruses30, 31. Each year, a total of 640,000 cancers are caused by human papillomaviruses (HPVs) alone32. The etiological role of HPV in cervical carcinoma was first proposed in the 1970s by zur Hausen. Recent research indicates that HPV accounts for more than half of infection-linked cancers in females33, 34. von Knebel Doeberitz . 35 reported that HPV infects human epithelial cells, integrates into their DNA, and produces oncoproteins including E6 and E7. The oncoproteins are able to disrupt the natural tumor suppressor pathways and inhibit apoptosis. This permits the proliferation of cervical carcinoma cells. HPVs have also been determined to be the main cause of other human cancers including skin cancers in immunosuppressed patients36, head and neck tumors37, and other anogenital cancers38. Rusan . (2015)39described 3 main pathways for HPV integration and tumorigenesis: an increase in oncogene expression, a loss of function of the tumor suppressor genes, and inter- and intra-chromosomal rearrangements. Langsfeld (2016)40 studied the life cycle of HPV and cervical cancer induction and reported that when the viral genomes migrate to the nucleus of the cervical epithelial cells (maintained at 100 copies/cell), the virus is continuously amplified in the daughter cells. The expression of oncoproteins (E6 and E7) is increased, leading to a significant enhancement of the cells' proliferation and the accumulation of cellular mutations41. This leads to a loss of cellular differentiation and the cancerous cells invading the dermal layer and neighboring tissues. Figure 1 illustrates the life cycle of HPV during cancer formation as well as the epithelial architecture before and after the virally induced cancer.

Life cycle and cancer formation of

Human herpes viruses are a family of oncogenic viruses. This family includes human herpesvirus-8, the main causal agent of Kaposi’s sarcoma and human herpesvirus-6, which has been found to be significantly related to the etiologies of brain cancers and lymphomas43, 44. Although the tumorigenesis mechanisms of these viruses have not yet been firmly established, many studies have suggested that several attributes of these viruses that can promote tumorigenesis45, 46. Choi . (2020) 46 investigated the mechanism of tumorigenesis in human herpesvirus and revealed that upon viral infection, the virus increases the metabolites of non-essential amino acids. The K1 oncoprotein of the viruses interacts with and activates the Pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase enzyme, leading to an increase in the intracellular concentrations of proline. Consequently, the interaction of the viruses' K1 oncoprotein and the reductase enzyme promotes tumorigenesis and tumor cell growth. Kang . (2017) 47 reviewed Kaposi’s sarcoma–associated herpesvirus and reported its ability to cause various tumors in humans. The tumors begin with the infection of the endothelial and B- cells by Kaposi's sarcoma–associated herpesvirus, leading to the formation of 1 of 3 malignancies, including Kaposi’s sarcoma and 2 B-cell lymphomas. In the early stages of the endothelial tumor infection (Kaposi's sarcoma), predominant inflammation and aberrant neoangiogenesis have been reported. However, in the later stages due to the proliferation of infected spindle cells, a serious modification of newly formed endothelial cell has been observed, although the origin of the endothelial cells remains elusive48. The increased rate of proliferation of the modified endothelial cells, in addition to its angiogenic and migratory capacities, is the primary mechanism of Kaposi's sarcoma oncogenesis as posited in the previous research.

The Hepatitis C virus belongs to a group of enveloped RNA viruses from the flavivirus family. It is the causative agent for both acute and chronic hepatitis49. In contrast, hepatitis B virus is a DNA virus from a different family, hepadnaviridae50. However, the diseases that result from both hepatitis C and B share many similarities. El-Serag et al. (2012) 51 estimated that roughly 80% of hepatocellular carcinomas worldwide are associated with chronic infections of hepatitis B virus and/or hepatitis C virus. Different studies have found there to be a relationship between intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and the hepatitis C or B viruses52. Worldwide, it has been estimated that 2 billion people are infected with hepatitis B virus, and that 1.2 million deaths every year are attributed to subsequent cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs), and hepatitis53. A meta-analysis performed in China that included 39 studies from 1954 to 2010 revealed that more than 70% of hepatocellular carcinomas were associated with hepatitis B virus infection, 5% with hepatitis C virus infection, and 6% with hepatitis B and C co-infection, although up to 19% of hepatocellular carcinoma cases showed no relationship with hepatitis B or C54. The majority of patients infected with both viruses developed a chronic hepatitis infection followed by inflammation-induced lesions. This triggered the secretion of various cytokines in the liver55, 56. As a result of these events, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma were likely to develop. Vescovo . (2016) 57 studied the molecular mechanisms of human hepatitis C virus and reported that HCC is a multistep process that leads to malignant transformation. This begins with the viral infection, chronic inflammation, and induction of lesions, followed by fat accumulation (steatohepatitis) in addition to progressive fibrosis. This process occurs over a period of 20 to 40 years, and 10 — 20% of patients went on to develop cirrhosis, whereas 1 — 5% developed typical HCC. The malignant transformation of the liver cells (hepatocytes) occurs due to the increased liver cell turnover resulting from chronic liver injury and subsequent regeneration57. The chronicity of these events, in addition to the oxidative stress, promotes and directly up-regulates the mitogenic pathways that block apoptosis, enhancing cell proliferation and inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS). Hepatitis viruses also triggers the immune response to produce several cytokines such as LTα and LTβ, which have been reported to play a vital role in HCC development58. The prolonged release of ROS is considered to be the main source of genetic mutations and tumorigenesis. Figure 2 presents the role and mechanisms of the hepatitis C virus from infection to HCC.

Mechanisms of Hepatitis C virus carcinogenesis from infection to hepatocellular carcinoma. A) Structural and non-structural proteins that play role in hepatocellular carcinoma B). Adapted from Hayes

Epstein-Barr virus is a herpesvirus that has a large genome consisting of double-stranded DNA. This encodes all of the enzymes involved in the replication of its DNA and in nucleotide biosynthesis60. It has been linked to a number of malignancies, such as Hodgkin’s disease61, B- and T-cell lymphomas62, leiomyosarcomas63, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease64, and nasopharyngeal carcinomas65. Among all of these cancers, the frequency of Burkitt’s lymphoma, leiomyosarcomas and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease have dramatically increased in the past few years especially in patients who suffer from immunodeficiency, revealing the role of immunosurveillance in the prevention and suppression of malignant transformation66. Naseem . (2018) 67 reported multiple factors associated with EBV that contribute to tumorigenesis, including inflammatory changes induced by the viral attack, the hypermethylation of the tumor suppressor genes, the induction of changes in the cell cycle pathways, and host immune evasion by the virus.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a carcinogenic virus derived from the lentivirus family. It is responsible for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and it has resulted in more than 20 million deaths worldwide68. Individuals with HIV have been reported to have a significantly higher incidence of various malignancies compared with the general population due to the progressive immune dysfunction69. Lung cancer is the most common HIV-related cancer, as demonstrated by many studies. However, the underlying mechanism of HIV is still poorly known70, 71. In one study 72, the authors suggested that cancer patients who are infected with HIV have a poorer prognosis compared to non-infected cancer patients. It has been reported that approximately 40% of HIV-associated malignancies were found to be associated with other oncogenic viruses such as EBV, human herpesvirus, HPV, and hepatitis B and C viruses73. Kaposi's sarcoma is an angioproliferative tumor that results from the Human herpesvirus-8 infection of cells of endothelial lineage in HIV patients74. Anampa . (2020)75 studied the mechanism of HIV carcinogenesis and reported that the viral infection itself appeared not to be directly involved in carcinogenesis. Instead, it disrupts the immune surveillance of tumors and other carcinogenic pathogens. The same authors reported that HIV induces cytokine dysregulation and genetic alterations, both of which enhance the potential for carcinogenesis. Furthermore, HIV is associated with chronic antigen stimulation which promotes lymphomagenesis75.

Human T lymphotropic virus type I is a type of single-stranded RNA retrovirus characterized by slow transformation and associated with adult T-cell leukemia76. The genome of this virus contains two long-terminal repeats and encodes for several genes, such as flanking gag, env, and pol, in addition to other accessory genes. These genes have been postulated to play a significant role in tumorigenesis77. Several proteins in Human T lymphotropic virus type I have been demonstrated to play key roles in cancer induction through cellular transformation as well as the immortalization of infected T lymphocytes78. It is of note that the Human T lymphotropic virus type I oncoprotein Tax inhibits the innate IFN immune response by mediating an interaction between the mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein, the stimulator of interferon, and the receptors interacting with protein 1. This interaction causes the suppression of the TANK-binding kinase 1 enzyme–mediated phosphorylation of IFN regulatory factor 3/IFN regulatory factor 779. The accessory protein of Human T lymphotropic virus, the leucine zipper factor, disrupts genomic integrity and inhibits apoptosis as well as the autophagy of the target cells. This leads to the enhancement of cell proliferation and facilitates its evasion from immune surveillance. This mediates oncogenesis78.

Carcinogenic bacteria

Recently, a significant number of studies have implicated that different types of bacteria are involved in the etiology of some cancer types, including in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue cancer80 as well as gastric cancer81, in gallbladder cancer82, in colon cancer83, and in cervical cancer84. This has inspired researchers to further study the mechanisms through which these bacteria promote oncogenesis in order to provide evidence to support such a role. is the most abundant bacterial species in the gastric epithelium due to its ability to resist and adapt to gastric acidity. Its presence has been markedly associated with the development of gastric and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue cancers. A significant number of researchers have linked infections with gastric cancer and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue cancer85, 86, 87, 88, considering it to be among the most important, if not the top, risk factor for gastric cancer in the world. Posselt . (2017) 89 studied the mechanism of gastric cancer induction by and reported that upon infection, the bacteria actively interferes with the host gastric cells via the secretion of bacterial proteases and the activation of cellular proteases. This may be involved in the induction of cancer. regulates and controls the secretion of proteases and thus hosts cytokines in early and late pathogenesis90. It has been reported that continuously induces various transcription factors and proteases, including disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) and various types of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). It can highly secrete the host cytokines and interfere with the extracellular matrix proteins or lateral junction complexes91. The chronic ulceration that results from pathogenesis will eventually lead to cell proliferation and the formation of tumors89. Figure 3 summarizes the mechanisms of gastric cancer induction by

Mechanisms of gastric cancer induction by H. pylori. A) Secretion of various transcription factors which can directly shed cytokines. B) Advanced stage of infection where proteases are implicated in cell pro

Alfarouk . (2019)92 studied the possible role of in gastric cancer and revealed that the carcinogenicity of such bacteria depends on bacteria–host related factors. They reported several genes expressed by the bacteria that accelerate its pathogenicity, in addition to the remodeling of the microenvironment including urease, carbonic anhydrase, Lewis antigen, vacA, cagA, and babA2. The variety of these virulence factors as mucys in helps to stabilize its population size in the stomach. This leads to the induction of chronic inflammation93. This creates an unfavorable habitat that alters the pH due to the chronic inflammation around the normal gastric cells. This instigates their malignant transformation and provides an accurate marker of gastric cancer94, 95. The transformation of gastric cells might be our bodies' normal defense against as various environmental changes elicit phenotypic plasticity in the gastric cells, enabling them to take on acidophilic phenotypes.

has been reported to be one of the major causes of colorectal cancer96. In one study, Chen. (2020)83reported that accelerates colonization by producing a biofilm in the intestinal tract. This causes a series of inflammatory reactions that result from toxin production. The accumulation of toxin may lead to severe tissue injury and chronic intestinal inflammation which may then develop into colorectal cancer. Snezhkina . 97 investigated the mechanisms of colorectal cancer formation by and found that bacterial enterotoxins are able to activate spermine oxidase from the host cells. This produces HO and spermidine as the byproducts of polyamine catabolism. These compounds significantly induce an inflammatory response leading to tissue injury and disturbance. The same authors found two mediators, namely c-Myc and C/EBP𝛽 to be overexpressed in tumors. These mediators play a significant role in cell proliferation, inflammation, and metabolic reprogramming.

is another pathogenic bacteria that has been linked to the malignant transformation of the gallbladder98. has the potential to promote carcinogenesis due to the production of various secretions such as nitroso compounds, bacterial glucuronidase, and toxic molecules. Cytolethal distending toxins are groups of toxins produced by that are able to trigger irreversible cell cycle arrest and apoptosis resulting from DNA damage99. Di Domenico . (2017)100 reported that the typhoid toxin produced by has strong carcinogenic potential as it induces DNA damage which leads to various alterations in the cell cycle of intoxicated cells101. Furthermore, the biofilm production of has been linked to tumorigenesis by promoting a persistent infection in the gallbladder. This leads to a chronic local inflammatory response that exposes the epithelial cells to severe and repeated damage. The presence of chronic infection around gallstones may enhance the formation of an biofilm, allowing the bacterial cells to detach from the gallstones and release various carcinogenic molecules. This induce genomic instability in the gallbladder epithelial cells and leads to tumorigenesis100. Figure 4 presents the proposed mechanisms by which may induce gallbladder cancer.

Proposed mechanisms for the induction of gallbladder cancer by

has been reported to be involved in the process of cell proliferation and the inhibition of apoptosis. The induction of chronic inflammation by and the same as a potential cause of cervical cancer was studied by Zhu . (2016)84. The authors concluded that individuals infected with have a significantly higher risk of cervical cancer. In a different study, Laban (2019)102 evaluated the association of infection with high-grade serous ovarian cancers and tubal carcinoma. The authors detected bacterial DNA in 84% of high-grade tubal serous cancers which revealed the strong relationship between and this type of cancer. Although these findings have not yet been supported by a suggested mechanism of carcinogenicity, these findings need to be replicated and further investigated to understand the potential role of in ovarian and cervical cancers.

Carcinogenic parasites

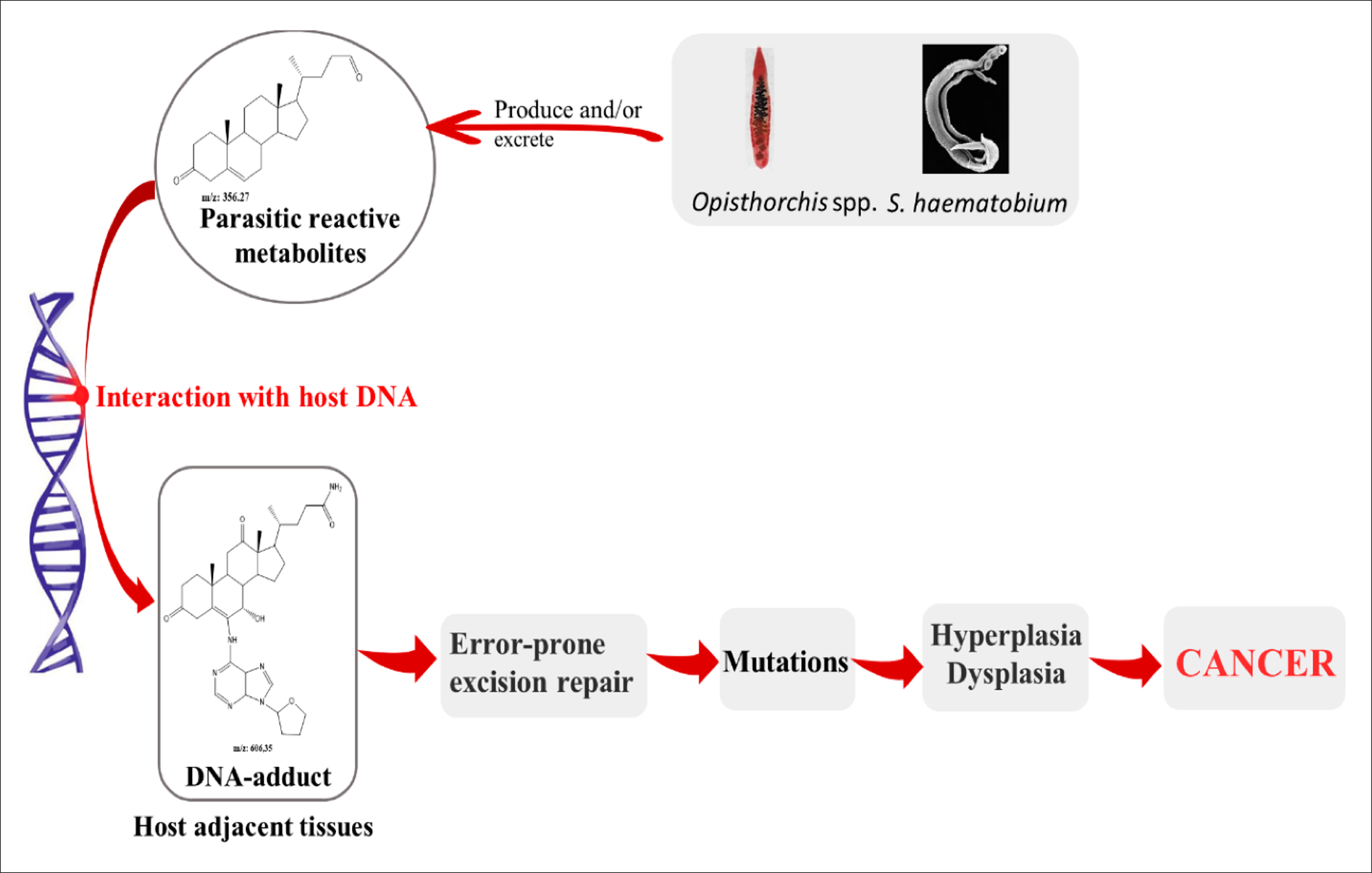

The associations between parasitic infections and cancers have been well established in numerous studies103, 104, 105, 106 (103-106). , and have been reported to be among the most carcinogenic parasites107, whereas other infectious species have been linked due to being the potential cause of cancers, especially the genera and 108. Many mechanisms have been suggested for carcinogenic parasites. Among them, 3 have been described for liver flukes, including metabolic oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and tissue damage due to parasitic attack109. Van Tong et al. (2017)110 studied the relationship between carcinogenesis and human malignancy in different parasites and revealed the high carcinogenicity of 3 helminth diseases including schistosomiasis, clonorchiasis, and opisthorchiasis. The authors illustrated the proposed mechanisms for cancer induction as presented in Figure 5. The chronic inflammation induced by the parasitic infections leads to the enhanced activation of many signaling pathways. This eventually generate somatic mutations that may activate oncogenes111.

Proposed carcinogenic mechanisms of

The metabolite secretions of , and species into the microenvironment of the host may induce metabolic processes such as oxidative stress which facilitates chromosomal DNA damage of the host cells, leading them to becoming cancerous113. The physical damage of host tissues due to parasitic attack, together with the immune response and wound healing process, lead to the secretion of various cytokines to increase cell proliferation and transformation. This also increases the potential for DNA damage and/or mutations114. Combined parasite–host interaction events, namely physical damage, parasite-derived products and chronic inflammation, as well as the combined effects on these processes on the host tissue and their DNA, leads to significant modifications and a higher risk of carcinogenesis due to changes in the cells' growth rate and proliferation, in addition to their survival. This in turn may initiate tumorigenesis and promote malignancy110.

Mechanism of carcinogenesis of parasitic pathogens

|

Parasitic pathogens |

Disease |

Associated cancer |

Proposed mechanism of carcinogenesis |

Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cryptosporidium parvum |

Cryptosporidiosis |

Colorectal cancer |

Inhibit apoptosis and enhance cells proliferation |

|

|

Schistosoma mansoni |

Schistosomiasis |

Colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma |

Chronic inflammation, and oxidative stress |

|

|

Schistosoma japonicum |

Schistosomiasis |

Colorectal cancer and squamous cell carcinoma |

Chronic inflammation, and oxidative stress |

|

|

Schistosoma haematobium |

Schistosomiasis |

Urinary bladder cancer, squamous cell carcinoma |

Chronic inflammation, and oxidative stress |

|

|

Blastocystis hominis |

Blastocystis infection |

Colorectal cancer |

Signaling induction, leading to impaired apoptosis |

|

|

Toxoplasma gondii |

Toxoplasmosis |

Brain cancer, meningioma and glioma |

Triggering a chronic inflammatory and alteration of cell signaling. |

|

|

Clonorchis sinensis |

Clonorchiasis |

Cholangiocarcinoma |

Chronic inflammation, cell proliferation & oxidative stress |

|

|

Trichomonas vaginalis |

Vaginitis and urethritis |

Prostate, cervical and reproductive tract, cancers |

Triggering of proto-oncogenes and altering junctional protein expression |

|

|

Plasmodium falciparum |

Malaria |

Burkitt lymphoma |

Immune suppression for carcinogenic viruses |

|

|

Opistorchis viverrini |

Opisthorchiasis |

Cholangiocarcinoma |

Chronic inflammation, cell proliferation & oxidative stress |

|

|

Taenia solium |

Neurocysticercosis |

Gliomas |

Chronic inflammation and cellular proliferation |

|

Carcinogenic fungi

Recent studies have revealed that fungi in the human gut can move into the pancreas under certain circumstances, triggering changes in the pancreatic cells that can lead to tumorigenesis126. Aykut. (2019)127 found that the fungal component of the pancreatic microbiome are significantly altered in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. In fact, several fungal genera promote tumor formation. Similarly, Malik (2018)128 found that common resident gut fungi can promote the activation of inflammasome during azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate–induced colitis in a mouse model. The authors reported that such fungi were able to alter the cell signaling during inflammasome activation. This resulted in the secretion of various cytokines including interleukin (IL)-18 and interferon-γ, suggesting that during spleen tyrosine kinase-caspase recruitment, domain-9 signaling maintains a microbial—or specifically fungal—ecology that promotes the activation of inflammasome and thus restrains colitis and colon tumorigenesis128. species are the most common fungal species in mammalian skin, and they are the best-studied fungal species in skin conditions include atopic dermatitis and dandruff129. Some studies have reported that inflammation caused by the overgrowth of may worsen gastric ulcers, weakening the immune system and changing the cell-surface signaling130, 131, 132, 133. Therefore, an abundance of species in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma tumors may be medically relevant. Aykut . (2019)127 found that the administration of antifungal drugs halted pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression in mouse models and significantly improved the ability of chemotherapy, leading to significant shrinking of the tumors. Interestingly, the subsequent repopulation of healed lab animals by a fungal species significantly accelerated the growth of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma again134. Not much work has considered the relationship between different fungi and cancers but these findings suggests that any microorganism is able to change the normal nature of the human body, making it a potential cause of cancer.

Cancer prevention and health precautions

In the age of personalized medicine and self-treatment, it is extremely important to isolate the causes of health issues to effectively plan personalized therapy. Various epidemiological studies have revealed that leisure time and physical activity can significantly reduce and even prevent at least 13 types of cancer95, 135. Other studies have provided evidence that exercise significantly reduces the risk of developing breast, colon, and prostate cancers136, 137. The nature and duration of exercise training involves whole-body homeostasis. This leads to the widespread adaptation of the body’s cells, tissues, and organs138, 139. Various systemic factors such as the release of catecholamines and myokines during exercise, in addition to sympathetic activation, shear stress, increase blood flow, and an increase body temperature. All immediately exert stress on tumor metabolism and homeostasis140, 141. These acute effects in the long-term will lead to improved blood perfusion, metabolism adjustments, enhanced immunogenicity, and intratumoral adaptations, contributing to slower tumor progression142. Various probiotic strains have been used to treat microbial infections, especially gastrointestinal tract infections, to boost human health as well as to control the biofilm formation that may lead to tumorigenesis143. Jacouton (2017)144evaluated the role of in colorectal cancer prevention and revealed that it had an immunomodulatory effect mediated by the regulation of different cytokines (particularly IL-22). This was in addition to an antiproliferative effect mediated by Bik, caspase-7 and caspase-9 regulation. The authors suggested using these probiotics in food supplements as a promising strategy for cancer prevention. In a different study, anti-biofilm properties were evaluated in cocktails of probiotic strains against and strains. They were demonstrated to be highly preventive of tumorigenesis inflammation145, 146. Hindering the biofilm formation of pathogenic gut microbes is said to be an effective method of cancer prevention for which certain strains of probiotic can be utilized147, 148. The production of antagonistic compounds, the modulation of the host immune responses, and competition with pathogens are among the mechanisms that have been suggested due to the beneficial role that probiotics appear to play, as Figure 6 illustrates149. Natural products have been screened for their anticancer properties, and many have been used in the development of cancer preventive and anticancer drugs150. Most anticancer drugs that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration of the United States are either natural or they mimic natural products151. Song (2016)152 reported that the prevention of any disease requires either the avoidance or reduction of risk factors (, carcinogenic materials or microorganisms) or the early detection of and intervention in disease evolution. In this regard, following a natural diet regime and avoiding oxidants and synthetic materials are major factors that may limit tumorigenesis in addition to boosting the immune system to help combat carcinogenic microorganisms. Figure 6 presents the mechanisms by which probiotics target tumorigenic gut microbial biofilms.

Schematic illustration of probiotic mechanisms targeting tumorigenic gut microbial biofilms. Adapted from Chew et al. (2020)

Conclusion

Recent research has uncovered a great deal of information regarding the mechanisms used by different microorganisms to cause, colonize, or cure cancer. However, many questions remain. It has long been known that many microorganisms can trigger tumorigenesis in humans but to date, the exact molecular mechanisms of many of these microbes have remained unclear. The continued exploration of these questions will bring research ever closer to the prevention, early diagnosis, and truly effective treatment of this scourge of mankind. Here we have discussed the role of viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and fungi in tumorigenesis and elucidated the possible molecular events that may be involved in the carcinogenic properties of each type of pathogen. We have also explored the structural basis for how the host cells interact with these microorganisms to produce the hallmarks of cancer. Microbial secretions, as well as immune-regulating cytokines, may play an essential role as mutagenic factors.

Abbreviations

AIDS: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid

EBV: Epstein-Barr virus

HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma

HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus

HPV: Human papilloma virus

IL: Interleukin

ROS: Reactive oxygen species

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the collaboration between Sabratha University, Sabratha, Libya, University Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, Malaysia and the Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia that made this work possible.

Author’s contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.