Cardioprotective Effects of Aqueous Extract of Ripped Musa paradisiaca Peel in Isoproterenol Induced Myocardial Infarction Rat Model

- Department of Veterinary Physiology and Biochemistry, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Ilorin, P.M.B. 1515, Ilorin Nigeria

- Phytomedicine, Toxicology and Drug Development Labouratory, Department of Medical Biochemistry and Pharmacology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Kwara State University, Malete, P.M.B. 1530, Ilorin Nigeria

- Department of Veterinary Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Ilorin, P.M.B. 1515, Ilorin Nigeria

- Department of Veterinary Microbiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Ilorin, P.M.B. 1515, Ilorin Nigeria

Abstract

Background: Myocardial infarction (MI) is the leading cause of cardiovascular deaths worldwide. Musa paradisiaca has been reported to contain secondary metabolites with antioxidant properties. This study investigated the possible cardioprotective effects of aqueous ripped Musa paradisiaca peel extract (MPPE) in an isoproterenol (ISO)-induced MI rat model relative to aspirin as a standard drug.

Methods: The MPP was extracted in distilled water using cold extraction; thereafter, MPPE was screened for secondary metabolites using standard biochemical methods. Investigation on the acute toxicity of MPPE was done in compliance with ARRIVE guidelines. Cardioprotective effects of the extract were established using biochemical assays (ELISA technique), an electrocardiogram, and a histological examination. We analyzed the data using a graphical prism version 5.03.

Results: The screening of MPPE revealed the presence of secondary metabolites, including flavonoids and phenols. The LD50 was above 5000 mg/kg. Rats administered ISO developed MI evidenced by increased cardiac troponin-I (cTn-I), pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1b , IL-6, and TNF-α), malondialdehyde, and ST segment elevation on the ECG. Further, there was a reduction in antioxidant enzymes and membrane-bound Na+/K+ATPase activities. Pre-treatment with MPP promoted restoration of cardiomyocytes with no side effect compared to aspirin. Significantly, it increased CAT, SOD, and Na+/K+ ATPase activities and decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines, MDA, and cTn-I, thereby reducing the elevation of ST-segment on the ECG to near normal. Results from the histopathological study support the cardioprotective effects of MPP.

Conclusion: The MPP confers protection to the myocardium through its antioxidant and anti-peroxidation properties that act as possible mechanisms in ISO-induced MI in rat models.

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI), characterized by the hypoxic state of myocardial tissue sequel to uneven perfusion of coronary blood supply compared to demand, is a leading cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in men1. MI causes myocardial ischemic injury and damage to the cardiomyocytes. The repair of damaged hearts in patients is challenging due to the limited ability of the cardiomyocytes to regenerate post-mitotically. Prolonged evident ischemia in chronic MI eventually leads to permanent myocardial cell injury or death2.

Citizens from low and middle-income countries, such as sub-Sahara Africa, including Nigeria, are more vulnerable to MI, with an increasing number of cases recorded in adults owing to habits and lifestyle such as excessive consumption of junk food, a lack of physical exercise, an over-labored working condition, and poverty3.

Previous reports suggest that the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) causing oxidative changes to the macro-molecules during ischemic damage played a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of MI with the deleterious consequence, evidenced by the elevation of cardiac troponin-I (cTn-I), the upregulation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukine-1 (IL-1β) and interleukine-6 (IL-6), and tissue necrotic factor (TNF-α)2. In addition, MI manifests by impaired sodium-potassium ATPase activity and electrocardiogram alterations together with histopathology changes4, 5.

Therapy with agents possessing antioxidant properties is of great interest due to the overwhelming evidence implicating oxidative stress sequel to increased production of free radicals during the pathogenesis of MI6. However, the limitations (such as a high level of toxicity and low aqueous solubility) observed following the use of synthetic antioxidants in preventing cardiovascular diseases have shifted the attention of researchers to the use of naturally derived antioxidants, owing to their high safety margin, cultural acceptability, and promised efficacy7.

Banana is the common term used to refer to several hybrids in the genus . Plantain, , is considered a good food source of natural antioxidants against cancer and heart disease8. It is widely consumed without apparent toxic effects, and its antioxidant properties have been traced to its presence of vitamin C, vitamin E, β-carotene, and dopamine. The report showed that peels of constitute about 40% of the total weight of the fresh fruit and displayed reasonable antimicrobial and antioxidant activities in both ethyl acetate and water-soluble extracts9, 10. In addition, several secondary metabolites (flavonoids, phenols, tannins, alkaloids, and glycosides) have also been isolated from plantain peels suggesting its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects8.

For over 25 years, aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) has been known for its role in preventing MI and ischemic stroke through its anti-thrombotic effect11. Aspirin displays an antiplatelet effect at low doses, thus prolonging bleeding time by selectively inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX)-I, an enzyme that produces the platelet antagonist thromboxane A2, and acting as an effective vasoconstrictor12. Based on the chemical constituent and reported activities of plantain peel, the present study aims to evaluate the cardioprotective effects of the aqueous extract of riped peels following isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction.

Material and methods

Material

A commercial grade standard of H906 (25 g) marketed as Isoprenaline HCl (98% HPLC) was obtained from AK Scientific, Inc, USA. Aspirin, the standard drug used, was procured from Bioraj pharmaceuticals, Nigeria. Pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) and cTn-I test kits were obtained from Junjiang Inter. Bldg Shanghai, China, and Calbiotech, California, USA, respectively. Other reagents and chemicals used were of analytical grades.

Plant material and extraction

Freshly ripped peels of were collected from a major food canteen at Malete, Kwara State, Nigeria. The plantwas identified at the herbarium of the Department of Plant Biology, University of Ilorin, Nigeria, and the voucher specimen (UIL/001/2019/1381) was deposited at the herbarium for reference purposes. After rinsing in distilled water, the peels were air-dried to a constant weight in the laboratory at room temperature (25 ± 2.0 °C) and pulverized to a powdered form using a kitchen blender (Nakai Japan, China). The powdered samples were kept in an airtight container until ready for use.

One kilogram of powdered peels was extracted in 5 Litres (L) of distilled water using the cold maceration method13. Thereafter, the solution was filtered with Whatman No 1 filter (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The filtrate was concentrated using a hot air oven (Surgifield Medical, Germany) set at 30 °C and thereafter preserved at 4 °C in a refrigerator until required for use. The extract was subjected to GC-MS. The Percentage yield (22.4 %) was determined, after which the extract was reconstituted with distilled water to a final concentration of 200 mg/mL.

Phytochemical Screening for Secondary Metabolites

The peel extract was evaluated for the presence of secondary metabolites by using standard methods14.

Determination of Bioactive compounds contained in peels using GC-MS

Bioactive compounds contained in the extract were analyzed in a GC-MS (Shimadzu, Kyoto) QP2010S that was fitted with a 1.4 µm column Rxi-5sil MS 30-meter length, 0.25 µm film thickness, and 0.25 mm inner diameter. The carrier gas was helium with a flow rate of 0.98 ml/min, column temperature 80 ºC, initial temperature 70 ºC, injector temperature 260 ºC, and detector temperature 300 ºC. The programmed linear temperature varied from 70 to 280 ºC at a rate of 10 ºC/min, operating in electron impact mode. The samples were injected in splitless mode. The interface temperature was kept at 280 ºC. Oven temperature programming was varied from 80 °C to 260 ºC at 10 ºC/min. The pressure of the carrier gas was kept at 63.6 kPa. The individual bioactive compounds were identified using the NIST 11 and WILEY 8 library based on the RT. Consequently, the name, molecular weight (MW), and structure of the components of the test materials were ascertained15.

Experimental animals

A total of 48 apparently healthy male Wistar rats (250 - 330 g) were acquired from an experimental animal unit of the Department of Veterinary Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Ilorin, Nigeria. The rats were distributed at random into 6 polypropylene cages (8 animals each) lined with wood shavings, renewed every 24 h. The animals were given access to pelletized vital feed (UAC, Nigeria) while water was provided Optimum temperature and humidity were maintained at 28 ± 2 ℃ and 65 ± 10%, respectively.

Acute toxicity testing

The median lethal dose (LD) was determined in accordance with the Organization of Economic Co-operation Development guidelines by a standard two-phase approach described by Lorke16. In the first phase, nine apparently healthy male Wistar rats (270 – 310 g) were distributed at random into 3 groups of 3 animals. The rats had fasted for 12 hours. Animals in each group (groups 1, 2, and 3) were given an aqueous extract of peels (P) orally, at 10, 100 and 1000 mg/kg body wt. respectively. Next, the rats were closely observed for 48 hours for signs of mortality or toxicity. Three rats were individually separated into 3 groups in the second phase of the approach. A rat in each group (groups 4, 5, and 6) was orally administered with extract at 1600, 2900, and 5000 mg/kg body wt. respectively. They were later monitored from the first 24 hours until 14 days for possible toxicity signs (sedation, salivation, lethargy, and muscular weakness) and mortality. The estimated value of LDwas thereafter determined by the previously described method13.

Induction of myocardial infarction in rats using isoproterenol

Myocardial infarction was induced in this study by a twice subcutaneous injection of isoproterenol hydrochloride (85 mg/kg body wt.) of 20 mg/ml concentration at a 24-hour intervals as previously described4 on days 15 and 16 of the study. The resultant elevation of cardiac troponin-I (cTn-I) in rats confirmed the occurrence of myocardial infarction.

Experimental Design

A total of 48 rats were used in this 16-day study. The animals were assigned at random into 6 groups (= 8) and treated as follows:

Group 1 (normal group): Rats were administered 1 ml of distilled water orally for 16 days.

Group 2(model group): Myocardial infarction was induced by subcutaneous injection of isoproterenol (85 mg/kg body wt.) at 24-hour intervals on days 15 and 16 of the study.

Groups 3, 4, 5, and 6 (preventive groups): For 14 days, rats in groups 3, 4, and 5 were pre-treated with peel extract (100, 200, and 400 mg/kg body wt. respectively). Also, rats in group 6 were pre-treated with aspirin (30 mg/kg body wt.) for 14 days. Myocardial infarction was then induced with a twice subcutaneous injection of isoproterenol (85 mg/kg body wt.) at 24-hour intervals on days 15 and 16 of the study.

Next, the rats were anesthetized using ketamine (100 mg/kg, intramuscular, i.m.) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.m.) on day 17 after fasting for 24 hours. Electrocardiogram readings of all rats were then taken, after which blood was withdrawn from all the rats by cardiac puncture into disposable blood collecting tubes devoid of anticoagulant (Shandong Medical Instrument Co., Ltd, Zibo, China). The blood samples were allowed to clot within 2 hours at 37 °C, followed by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 1000 × to obtained serum. The sera obtained as supernatants were collected using a plastic pipette into another sterile sample bottle. The rats were later sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The heart tissues were immediately harvested, rinsed in phosphate buffer solution, PBS (0.01 M and pH 7.4) to remove excess blood, and then weighed. The tissues were homogenized in PBS (pH 7.4) using a mortar and pestle and then thawed at 8 °C, after which they were centrifuged at 2000× for 20 minutes to give tissue homogenates. The serum and tissue homogenates were used to carry out biochemical assays as previously described17.

Estimation of Electrocardiogram

On day 17 of the study, ketamine (100 mg/kg, .) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.m.) were used to anesthetize the rats. The electrodes from EDAN (the ECG machine connected to the laptop) (Heal force biotech, Shanghai, China) were then fixed to the rat's forelimbs (skin above the elbow), hind limbs (just above stifle joint), and the heart18. On paper, the ECG recordings were produced using speed and sensitivity of 50 mm/s and 10 mm/mv respectively from the experimental animals, and ECG wave alterations were noted.

Biochemical assays

Serum levels of cardiac troponin-I (cTn-I) and the pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) were estimated by the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) technique using the standard kit (Calbiotech, California, USA, and Junjiang Inter. Bldg Shanghai, China) in accordance with manufacturer's instructions. The sodium-potassium ATPase activities in the tissue homogenate were measured by estimating the level of phosphorus liberated from the test samples19. The serum activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and Catalase (CAT) were determined according to the previously described method20. Serum lipid peroxide activities were determined by the previously described method21. Also, serum electrolytes (Na, K, Caand Cl) levels were determined following previously described protocols22.

Histopathological Examination

The hearts were washed with normal saline immediately after harvest and then fixed in 10% buffered neutral formalin, after which the heart tissues and coronary arteries were embedded in paraffin. After this, they were sectioned, stained (hematoxylin and eosin stain), and examined under a light microscope (x100)23. The slides were observed for evidence of inflammatory cells infiltration, necrosis, and edema.

Statistical Analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by multiple comparison test using Graphical prism version 5.03 (Graphical Software, San Diego, California, USA). The value of < 0.05 was considered a significant difference between and within groups and was denoted by letters.

Ethical statement

The experimental protocols were conducted in compliance with principles and guidelines of the ARRIVE guideline Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, the University of Ilorin Committees on Animal Use and Care (FVER/007/2019) and following the principles of laboratory animal care (NIH, 2011) guidelines.

Acute toxicity study of aqueous

|

Phase |

Number of rats |

Weight of rats (g) |

Dose (mg/mg) |

Signs of toxicity (OTS/HR)* |

Mortality (DR/SR)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

3 |

260 |

10 |

0/3 |

0/3 |

|

271 | |||||

|

310 | |||||

|

3 |

283 |

100 |

0/3 |

0/3 | |

|

286 | |||||

|

256 | |||||

|

3 |

315 |

1000 |

0/3 |

0/3 | |

|

270 | |||||

|

293 | |||||

|

2 |

1 |

325 |

1600 |

0/1 |

0/1 |

|

1 |

265 |

2900 |

0/1 |

0/1 | |

|

1 |

275 |

5000 |

0/1 |

0/1 |

Phytochemical screening of aqueous extract of

|

Chemical constituents |

Indications |

|---|---|

|

Saponin |

10.78 ± 0.04 |

|

Tannins |

5.77 ± 0.25 |

|

Phenolics |

13.12 ± 0.77 |

|

Phlebatannin |

Not detected |

|

Steroids |

99.40 ± 0.75 |

|

Flavonoids |

209.20 ± 0.39 |

|

Coumarins |

Not detected |

|

Anthocyanins |

0.17 ± 0.01 |

|

Terpenoids |

Not detected |

|

Glycosides |

4.40 ± 0.44 |

|

Triterpenes |

120.90 ± 9.33 |

|

Alkaloids |

6.47 ± 0.27 |

Chromatogram of aqueous

Bioactive compounds found in aqueous of

|

Peak |

Retention Time |

Area % |

Molecular formula |

Molecular weight (g/mol) |

Name of the compound |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

10.767 |

1.73 |

C2H4O |

44.05 |

Oxirane |

|

2 |

12.343 |

0.90 |

C10H14 |

134.22 |

1-methyl-3-(1-methylethyl) benzene |

|

3 |

13.644 |

1.29 |

C10H14 |

134.22 |

1,2,3,4-tetramethylbenzene |

|

4 |

15.790 |

3.24 |

C10H8 |

128.17 |

Naphthalene |

|

5 |

16.002 |

2.58 |

C5H10N2O |

114.15 |

1-Piperazinecarboxaldehyde |

|

6 |

17.935 |

0.72 |

C8H8O |

120.15 |

2,3-dihydrobenzofuran |

|

7 |

20.731 |

6.00 |

C9H10O2 |

150.18 |

1-(2-hydroxy-5-methylphenyl) ethanone |

|

8 |

21.626 |

1.33 |

C11H29O6PSi3 |

372.57 |

Acetic acid, [bis[(trimethylsilyl)oxy]- |

|

9 |

22.977 |

1.06 |

C9H17NO |

155.24 |

2-(tetrahydro-2-furanyl)Piperidine |

|

10 |

24.028 |

2.97 |

C10H13NO2 |

179.22 |

l-Phenylalanine, methyl ester |

|

11 |

26.993 |

7.51 |

C14H42O7Si7 |

519.07 |

Tetradecamethyl cycloheptasiloxane |

|

12 |

28.870 |

1.13 |

C11H11N |

157.21 |

3-Methyl-4-phenyl-1H-pyrrole |

|

13 |

31.753 |

2.95 |

C16H48O8Si8 |

593.20 |

Hexadecamethyl cyclooctasiloxane |

|

14 |

33.893 |

1.98 |

C9H10N2O2 |

178.19 |

5,6-Dimethoxybenzimidazole |

|

15 |

35.907 |

2.79 |

C18H54O9Si9 |

667.40 |

Octadecamethyl cyclononasiloxane |

|

16 |

36.939 |

6.29 |

C17H34O2 |

270.50 |

Methyl palmitate |

|

17 |

37.295 |

11.05 |

C16H32O2 |

256.42 |

n-Hexadecanoic acid |

|

18 |

37.489 |

2.27 |

C18H23N3 |

281.40 |

3,6-Bis(N-dimethylamino)-9-ethylcarbazole |

|

19 |

38.203 |

2.19 |

C19H34O2 |

294.5 |

methyl ester 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid |

|

20 |

38.240 |

8.92 |

C19H32O2 |

292.5 |

Methyl ester 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid |

|

21 |

38.321 |

9.18 |

C20H40O |

296.5 |

Phytol |

|

22 |

38.497 |

20.37 |

C18H32O |

264.4 |

(Z,Z,Z) 9,12,15-Octadecatrien-1-ol |

|

23 |

39.247 |

1.55 |

C16H17N3O2 |

283.32 |

Amonafide |

Effect of aqueous extract of

Results

Testing of acute toxicity

Rats in phases 1 and 2 administered with aqueous peel extract of varying doses showed no toxicity signs and mortality during the monitoring period of 14 days (

Secondary Metabolites Revealed by Phytochemical screening

From our study, the presence of some secondary metabolites was evidenced following the phytochemical screening. These include flavonoids, phenolics, saponins, tannins, steroids, anthocyanins, glycosides, triterpenes, and alkaloids. However, coumarins, terpenoids, and phlorotannins were not detected (

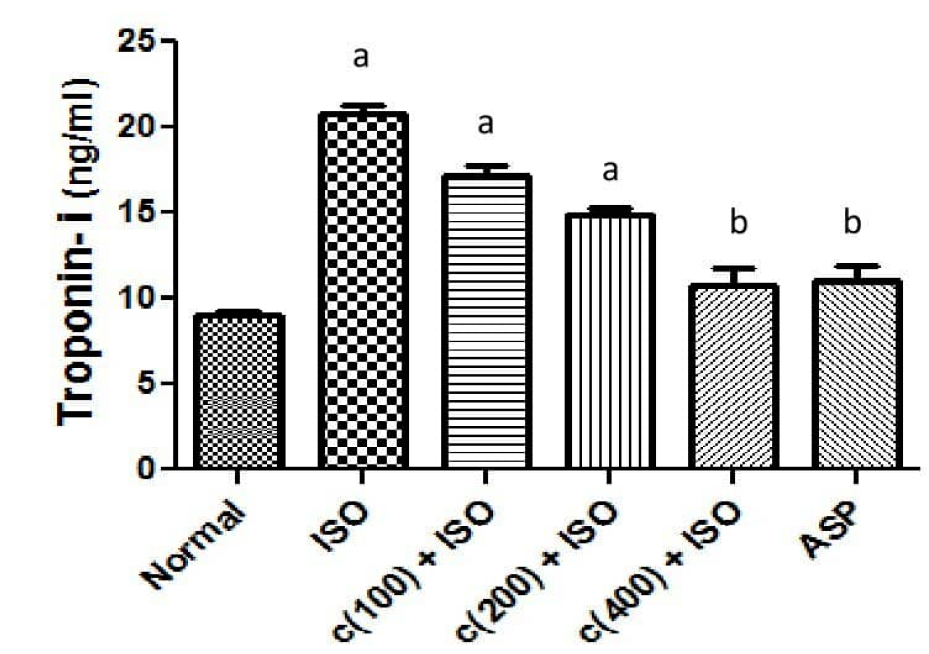

Data showing effects of cardiac trponin-I and Na+/K+ ATPase in isoproterenol induced myocardial infarcted rats

|

Treatment |

Troponil-I (ng/ml) |

Na+/K+ ATPase ( |

|---|---|---|

|

Normal control |

9.06 ± 0.59 |

3.06 × 10-4 ± 3.31 × 10-5 |

|

ISO |

20.75 ± 1.25 a |

1.40 × 10-4 ± 3.21 × 10-5a |

|

C(100) + ISO |

17.11 ± 1.60 a |

1.80 × 10-4 ± 3.62 × 10-5a |

|

C(200) + ISO |

14.84 ± 1.09 a |

2.05 × 10-4 ± 3.09 × 10-5 |

|

C(400) + ISO |

10.77 ± 2.14 b |

2.84 × 10-4 ± 2.93 × 10-5b |

|

ASP |

11.08 ± 1.82 b |

2.75 × 10-4 ± 2.60 × 10-5b |

Effect of aqueous extract

|

Treatment |

SOD ( |

CAT ( |

MDA (nmol/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Normal control |

1.15 ± 0.22 |

36.77 ± 1.22 |

11.24 ± 2.54 |

|

ISO |

0.24 ± 0.08 a |

20.89 ± 2.17 a |

27.44 ± 5.01 a |

|

C(100) + ISO |

0.35 ± 0.11 |

21.10 ± 2.24 |

25.22 ± 5.54 |

|

C(200) + ISO |

0.58 ± 0.09 |

26.82 ± 1.50 |

22.21 ± 3.94 b |

|

C(400) + ISO |

0.92 ± 0.17 b |

32.24 ± 1.94 b |

12.85 ± 1.38 b |

|

ASP |

0.84 ± 0.14 b |

31.72 ± 1.56 b |

13.34 ± 1.84 b |

Effect of aqueous extract of

Major bioactive compounds identified by GC-MS analysis

A total of 23 major peaks were revealed by the GC-MS chromatogram of aqueous peels (Figure 1). The identified compounds are presented with their peak, retention time (RT), area (%), molecular formula, and molecular weight (

Effect of treatmenton serum cardiac troponin-I (cTn-I)

Isoproterenol (ISO) treated group (model group) showed a significantly (P < 0.05) elevated serum troponin-I (cTn-I) concentration compared to the normal control group (Figure 2 and

Effect of treatment on Na/K ATPase activity in cardiomyocytes homogenate

The cardiomyocyte's homogenate activities of Na/K ATPase in the model group were significantly (P < 0.05) lowered compared to the normal control group (Figure 3 and

Effect of treatment on serum antioxidant enzymes (catalase, CAT, and superoxide dismutase, SOD) and lipid peroxidation (malondialdehyde, MDA) activities

Antioxidant enzymes were lowered (P < 0.05) in the model group compared to the normal group for serum levels of CAT and SOD (

Effect of aqueous extract of

|

Treatment |

IL-1β (pg/ml) |

IL-6 (pg/ml) |

TNF-α (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Normal control |

111.40 ± 1338 |

6.63 ± 1.96 |

84.22 ± 7.33 |

|

ISO |

218.30 ± 18.87 a |

22.96 ± 3.00 a |

162.80 ± 13.84 a |

|

C(100) + ISO |

210.00 ± 12.10 |

21.76 ± 3.22 |

141.50 ± 10.57 |

|

C(200) + ISO |

187.60 ± 23.26 |

15.65 ± 2.01 |

122.60 ± 4.39 |

|

C(400) + ISO |

116.00 ± 14.01 b |

10.46 ± 2.19 b |

99.86 ± 9.81 b |

|

ASP |

117.50 ± 14.53 |

11.90 ± 1.94 b |

101.90 ± 11.02 b |

Effect of treatment on serum pro-inflammatory cytokines: interleukine-1 (IL-1β), interleukine-6 (IL-6), and necrotic tissue factor (TNF-α)

Serum activities of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) in the model group were significantly (P < 0.05) increased compared to the normal group (

Effect of treatment on serum electrolytes levels

The activities of the serum electrolytes, Cland Ca, in the normal model and pre-treated groups, revealed no significant difference (P ˃ 0.05) except for reduced levels of Clin groups pre-treated with extracts at 100 and 200 mg/kg body wt. compared to the normal group (P < 0.05) (

Effect of aqueous extract of

|

Treatment |

Na+ (mmol/l) |

K+ (mmol/l) |

Cl- (mmol/l) |

Ca2+ (mmol/l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Normal control |

94.90 ± 2.22 |

6.21 ± 0.36 |

42.13 ± 3.87 a |

1.92 ± 0.11 a |

|

ISO |

80.21 ± 8.21 b |

3.30 ± 0.35 b |

42.83 ± 071 a |

1.73 ± 0.07 a |

|

C(100) + ISO |

89.30 ± 3.32 c |

4.00 ± 1.00 b |

39.01 ± 2.73 b |

1.72 ± 0.09 a |

|

C(200) + ISO |

89.30 ± 2.85 c |

4.47 ± 1.01 c |

37.72 ± 4.33 b |

1.61 ± 0.12 a |

|

C(400) + ISO |

92.79 ± 1.63 c |

5.33 ± 0.60 c |

42.74 ± 3.27 a |

1.73 ± 0.09 a |

|

ASP |

90.25 ± 3.62 c |

4.79 ± 0.88 c |

42.45 ± 2.37 a |

1.81 ± 0.25 a |

Electrocardiographic changes on ECG paper. (A) Normal control group showing regular R-R and normal PR interval.(B) Model group showing ST elevation, irregular R-R interval, ‘S’ is located on the isoelectric baseline and narrow QRS. (C) Group pre-treated with 100 mg/kg body wt. extract showing minimized ST elevation, narrow and shorter QRS and irregular R-R interval. (D) Group pre-treated with 200 mg/kg body wt. extract showinglocation of ‘S’ below the isoelectric baseline, atrial fibrillation and irregular R-R interval. (E) Group pre-treated with 30 mg/kg body wt. of aspirin showing atrial fibrillation and irregular R-R interval. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16903870.v1

Effect of aqueous extract of

Effect of treatment on electrocardiographic changes (electrical tracing on ECG paper) in isoproterenol-induced Myocardial Infarction

Figure 4A-F depict electrical tracings of cardiomyocytes (P, QRS, and T wave) in different groups on ECG paper. Normal R-R and PR intervals were observed in the normal group (Figure 4A), while the model group showed a taller and wider T wave evidenced by ST elevation, prolonged PR interval, narrow QRS complex, and irregular R-R interval (Figure 4B). Animals pre-treated with the extract's 100 mg/kg body weight revealed irregular an R-R interval, narrow QRS complex, and minimized ST elevation (Figure 4C). Consequently, pre-treatment with extract (Figure 4D) and aspirin (Figure 4F) at 200 and 30 mg/kg body wt. respectively before induction of myocardial infarction revealed atrial fibrillation and an irregular R-R interval. However, pre-treatment with 400 mg/kg body wt. extract showed a normal QRS complex and a reduced ST segment accompanied by repeated loops of T and P waves (Figure 4E).

Effect of treatment on histopathology of the myocardium by staining with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E x 100)

Following staining of the heart with H&E, histological assessment of the cardiomyocytes was carried out (Figure 5). Histological findings of cardiomyocytes from the normal group showed regular heart structure characterized by the absence of inflammatory cells and no observable cellular damage (Figure 5A). The model group revealed necrotic wavy cardiac muscle cells with degenerative cellular changes and heavy neutrophil infiltration (arrow) (Figure 5B). Mild necrotic areas with heavy neutrophil infiltration were evidenced (arrow) in the hearts of the group pre-treated with extract at 100 mg/kg body weight (Figure 5C). The group pre-treated with extract at 200 mg/kg body weight showed mild inflammation and proliferation of fibroblast, which progressively replaces necrotic cardiomyocyte (Figure 5D). Groups pre-treated with extract and aspirin at 400 and 30 mg/kg body weight respectively exhibited typically normal myocardium with the reduced consequence of myocardial infarction evidenced by less infiltration of inflammatory cells and few necrotic areas induced by subcutaneous injection of isoproterenol (Figure 5E & F).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effect of PE on the restoration of rats’ hearts in an ISO-induced model of MI using ASP as the reference drug. Manifestation of MI involves biochemical, electrocardiograph, hemodynamic, and histopathological alteration of the cardiomyocytes due to the reduction of endogenous antioxidants, escape of cardiac injury marker enzymes, and lipid peroxidation24. A reported protective effect of ASP in the hearts of myocardial infarcted subjects is attributed to its anti-thrombotic activity25. PE was previously reported to possess secondary metabolites responsible for their wide range of biological activities, including cardiovascular and antioxidant effects26.

The findings from the present study reveal that peel extract (PE) showed potential cardioprotective effects against ISO-induced MI most likely by ameliorating impaired cardiomyocytes Na/K ATPase activities and cTn-I leakages, supporting endogenous antioxidant defense system, hindering lipid peroxidation, restoring electrocardiograph ST elevation, promoting anti-inflammatory effects, and the histological preservation of cardiomyocytes evidenced by reduced myonecrosis with minimal inflammatory cells.

During the acute toxicity study, the aqueous extract of P was found to save even at the 5000 mg/kg dose. Consequently, in this study, geometrical progression doses of 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg were chosen to evaluate the cardioprotective effect of the extract.

In this study, the presence of secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, phenolics, tannins, steroids, alkaloids, and glycosides were established following a phytochemical screening of the aqueous PE. This aligns with findings from a previous study that documented their possession of multiple pharmacological and biological effects14. The presence of these secondary metabolites in the PE suggests explorable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potentials present in the peels of

The GC-MS analysis of extract revealed 23 bioactive compounds, many of which had been documented to exert a cardioprotective effect through their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities27, 28. As showed in our study, (Z,Z,Z) 9,12,15-Octadecatrien-1-ol and n-Hexadecanoic acid possessing maximum percentage peak area is documented to have antioxidant properties28, 29. Further, Methyl ester 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, and Phytol with a moderate percentage peak area have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties as reported in previous studies27, 29, 30. Methyl palmitate and methyl ester 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid were reported as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds, respectively28, 31.

Injection of isoproterenol (ISO) is regarded as the universal and convenient means by which MI is induced to evaluate anticipated cardioprotective agents as it causes similar pathophysiological and molecular changes in the heart of rats as compared to what is obtainable in humans1. Consequent upon isoproterenol administration, oxidative damage of cardiomyocytes results from the excessive generation of free radicals produced from autoxidation of catecholamine, causing a reduction in activities of endogenous antioxidant systems leading to inequality of pro-oxidant/antioxidant levels in the cardiomyocytes4.

Catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) are endogenous antioxidant enzymes that serve as a first-line defense against oxidative injury by scavenging free radicals and opposing the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The present study revealed a significant reduction in the activities of antioxidant enzymes (CAT and SOD) in animal models of ISO-induced myocardial infarction. This suggests oxidative damage to the cardiomyocytes due to the accumulation of free radicals32. Interestingly, serum levels of CAT and SOD were remarkably elevated in rats pre-treated with peel extract more than those of ASP, suggesting the presence of its antioxidant and free radical scavenging potentials as reported in a previous study9. Hence, the present study upholds the fact that peel extract displays a cardioprotective effect due to its antioxidant properties. Increased lipid peroxidation, evidenced by elevation of malondialdehyde (MDA) in ISO-induced MI rats, indicates the susceptibility of hearts to oxidative injury due to myocardial membrane damage following increased production of free radicals33. Pre-treatment with PE reduced the elevation of MDA relative to ASP in ISO-induced MI rats, thus revealing its cardioprotective effect possibly by scavenging accumulated free radicals consequently produced to ISO administration8.

Cardiac troponin-I (cTn-I) is a contractile protein reported to be a specific marker for myocardial cell injury found in the serum consequent to cardiomyocyte damage34. In this study, an increased serum cTn-I was attributed to damage to the sarcolemma following injection of ISO in ISO-induced MI rats, causing cTn-I leaks into the serum5. Conversely, ISO-induced MI rats pre-treated with peel extract had lowered serum levels of cTn-I, suggesting a cardioprotective effect of the extract by minimizing leakage of cTn-I as a result of its (PE) antioxidant effect.

Following MI or ischemic heart disease, inflammatory responses are essentially mediated in the heart by pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) that are implicated in the healing process post-MI35. A previous study reported elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines in both ISO-induced animal and human MI36. The present investigation revealed increased levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in ISO-induced MI rats reflecting ongoing inflammatory processes, which aligns with findings from the previous study. However, pre-treatment with PE protected the cardiac membrane from the deleterious effect of ISO-induced MI by assuming an antioxidant effect. This is reflected by reduction of the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 and a subsequent minimization of inflammation in the heart of ISO-induced MI rats. This effect followed a dose-dependent manner with the highest anti-inflammatory effect expressed in the group pre-treated with the extract's 400 mg/kg body wt.

The development of many diseases, including MI, are reported to occur due to the inability of the cell membrane to physiologically maintain the transmembrane ionic concentration5. The ubiquitous transmembrane protein Na/K ATPase predominantly regulates ionic (Na and K) balance across the cardiomyocytes, thereby contributing to cardiac contractility and membrane potential5, 37. Administration of ISO inhibited activities of Na/K-ATPase, thereby distorting movement of electrolytes across the membrane, indicating myocardial injury due to susceptibility of the enzymes' active site to free radical attack38. In a dose-dependent manner, pre-treatment with peel extract promotes restoration of Na/K-ATPase activities in the cardiomyocytes, which indicates the preservative potential of the extract on cardiomyocytes membrane by rendering it less leaky, consequent to the inhibition of lipid peroxidation and reduction in membrane disruption.

Electrocardiogram remains an important tool for clinical diagnosis of MI by recording the heart's electrical activity, thus forming the basis for instant therapeutic interventions when correctly interpreted1, 17. In the present study, a manifestation of ST segments elevation, prolonged PR interval, irregular R-R, and a narrow QRS complex observed in the ISO-induced group suggests ongoing myocardial necrosis and inflammation in the ventricles atrioventricular block caused by ISO injection39. Pre-treatment with peel extract in ISO-induced MI rats revealed a minimization of the atrial fibrillation effect of ISO administration in a dose-dependent manner relative to ASP, suggestive of its cell membrane protective effects. However, delay of the expected ECG pattern (near to normal) as observed in group pre-treated with 400 mg/kg body wt. of peel extract may be due to physiological adaptation to arrhythmogenic changes or ECG, or to ISO-induced MI in the pre-treatment group hearts, which may require a longer time for a complete reversal 1.

The balance of electrolytes in the body is essential for normal bodily cells and organ function, including the heart. Regulation of the heart's electrical activity depends on a normal level of calcium, potassium, and sodium, whereas optimum contraction of the heart requires calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus40. The reduction in serum activities of both Na and K following administration of ISO can be attributed to ongoing oxidative damage as a consequence of a free radical attack on the Na/K pump causing its impairment41. However, pre-treatment with peel extract resulted in the elevation of the electrolytes, Na and K, suggesting responsiveness of electrical conductivity of the heart.

Histopathological examination of myocardial tissue in normal control rats revealed no observable cellular damage evidenced with intact myocardial structure. The group administered ISO alone showed marked necrosis and infiltration of inflammatory cells4. However, pre-treatment with peel extract resulted in a reduced level of myonecrosis and a lowered level of inflammatory cells in a dose-dependent manner. This further buttressed the cardio-protective nature of peel extract in ISO-induced myocardial injury. This cardio-protective effect may be partly due to its antioxidant effect.

Therefore, we suggest further work on the isolation and identification of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of bioactive compounds as revealed by GC-MS analysis of extract. This would enable the discovery of novel drugs with adequate knowledge of their pharmacological activities. Also, echocardiography, in addition to electrocardiography, should be conducted to further give credence to the therapeutic claim of the reversal effect of extract.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated a positive prognosis of Musa paradisiaca peel extract (PE) by offering protection to the myocardium in ISO-induced myocardial infarction (MI) rats. The effect of PE in offering protection to the myocardium in ISO-induced MI rats may be due to its antioxidant effect. This investigation reaffirmed the antioxidant effect of PE. It demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effect responsible for minimizing oxidative stress, hindering elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α), and thereby promoting restoration of histoarchitecture of the myocardium in ISO-induced MI rats.

Abbreviations

CAT: Catalase

cTn-I: Cardiac troponin-I

ECG: Electrocardiograph

GC-MS: Gas Chromatography — Mass Spectrometry

IL-1β: Interleukine-1β

IL-6: Interleukine-6β

ISO: Isoproterenol

LD: Median lethal dose that could kill 50% of the population

MDA: Malondialdehyde

MI: Myocardial infarction

MPPE: peel extract

ROS: Reactive oxygen species

SOD: Superoxide dismutase

TNF-α: Tissue nectrosis factor alpha

Acknowledgments

Our sincerer appreciations go to the Vice Chancellor, University of Ilorin, Prof. Abdulkareem Agei by partly funding this research as well as Prof. S.F. Ambali of Department of Veterinary Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Ilorin, Nigeria for his support and encouragement during the course of this work.

Author’s contributions

(1) Conception and Study Design: Suleiman K.Y., Ajani E.O., Biobaku, K.T; (2)Toxicity determination: Akorede G.J., Biobaku, K.T., Suleiman K.Y.; (3) Extract dosage formulation: Aremu A., Suleiman K.Y.; (4) Biochemical assays analysis: Suleiman K.Y., Ajani E.O., Biobaku, K.T.; (5) ECG determination: Azeez M.O., Suleiman K.Y.; (6) Histopathology examination: Okediran B.S., Suleiman K.Y., Ahmed A.O.; (7) Acquisition of data: Suleiman K.Y., Akorede G.J.; (8) Data analysis and interpretation: Suleiman K.Y., Ajani E.O., Biobaku, K.T.; (9) Drafting of the article: Suleiman K.Y.; (10) Revision and proofreading: Suleiman K.Y., Ajani E.O., Biobaku, K.T., Ahmed A.O.; (11) Final approval: Suleiman K.Y., Ajani E.O., Biobaku, K.T., Okediran B.S., Azeez, M.O., Akorede G.J., Aremu A., Ahmed A.O.

Funding

The first Author declared that that research was partly funded by Vice Chancellor, University of Ilorin, Nigeria, Prof. Abdulkareem Agei through staff development award.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.